Ultra-Processed Food Addiction Is Rising Among Middle-Aged Adults — Especially Women Over 50

A new study has raised serious concerns about how deeply ultra-processed foods (UPFs) have become part of modern life — and how strongly they seem to “hook” people, especially middle-aged women. According to researchers from the University of Michigan, nearly one in five women aged 50 to 64 show signs of addiction to ultra-processed foods. For men in that same age group, about one in ten meet the same criteria.

The study, published in the journal Addiction, analyzed data from more than 2,000 adults aged 50 to 80 across the United States. Researchers wanted to understand how generations raised in different food environments might differ in their relationship to processed foods — and the findings are striking.

The First Processed Food Generation

The researchers point out that Generation X and younger Baby Boomers were the first Americans to grow up surrounded by ultra-processed foods. From childhood through adulthood, they were immersed in a world of fast food, packaged snacks, sugary cereals, and frozen “diet” meals — products engineered to be hyper-palatable with added fats, sugars, salt, and flavorings designed to stimulate reward centers in the brain.

This early exposure seems to have left a lasting mark. Adults now in their 50s and early 60s — the very first to grow up in this food environment — are showing far higher rates of addiction-like behavior toward these foods than older generations who encountered them later in life.

In contrast, adults aged 65 to 80 (those who spent their early lives in less processed food environments) show much lower rates of this form of addiction: only 12% of women and 4% of men met the addiction criteria.

Measuring Food Addiction

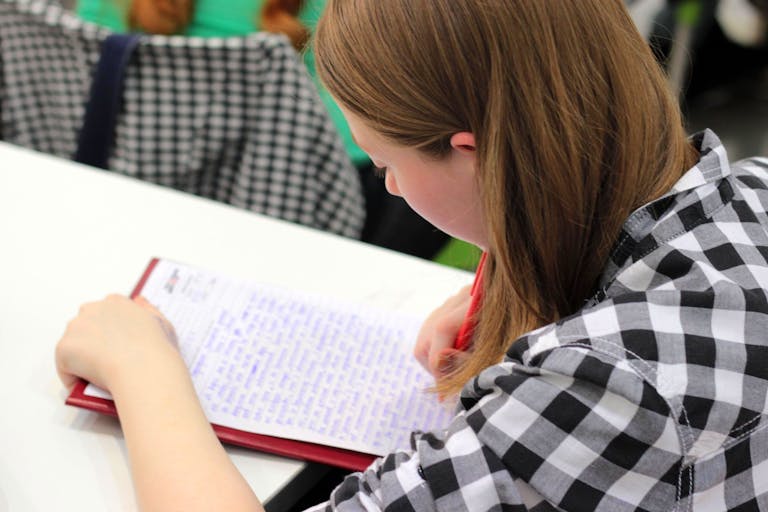

To determine addiction levels, researchers used a tool called the modified Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 (mYFAS 2.0). This scale is based on the same diagnostic criteria used for substance use disorders, but adapted for food. Participants were asked about 13 specific experiences with ultra-processed foods and drinks — such as strong cravings, failed attempts to cut down, withdrawal symptoms, or avoiding social situations out of fear of overeating.

The “substance” in question isn’t alcohol or nicotine — it’s the hyper-rewarding foods that dominate supermarket aisles and fast-food menus: sweets, salty snacks, burgers, fries, and sugary beverages.

By applying this addiction framework, the study highlights just how similar compulsive eating of ultra-processed foods can be to substance addiction. The same psychological patterns — craving, loss of control, withdrawal, and continued use despite harm — appear to be present.

Women Are Hit Harder

One of the most notable findings is that women are significantly more affected than men. Unlike traditional addictions such as alcohol or tobacco use (historically higher in men), ultra-processed food addiction is far more common in older women.

Researchers suspect that this may be connected to aggressive marketing of “diet” foods in the 1980s and 1990s. Many women in this generation grew up during the rise of low-fat and low-calorie snacks — products like fat-free cookies, meal-replacement bars, and microwavable “healthy” dinners. While these foods were advertised as tools for weight control, they were still heavily processed and engineered to stimulate cravings.

These so-called “diet” products may have encouraged cycles of restriction and reward, leading to patterns of compulsive eating over time. Add to that decades of societal pressure to stay thin, and it becomes clear why women of this generation may be particularly vulnerable.

Links to Weight, Health, and Isolation

The study also explored how ultra-processed food addiction relates to self-perception of weight, mental and physical health, and feelings of social isolation.

Weight Perception:

- Women who described themselves as overweight were 11 times more likely to meet the criteria for food addiction than those who felt their weight was about right.

- For men, that likelihood was even higher — they were 19 times more likely to qualify as food-addicted.

- Overall, about 31% of women and 26% of men in the study considered themselves overweight, while 40% of women and 39% of men saw themselves as slightly overweight.

Mental Health:

- Men reporting fair or poor mental health were four times more likely to show signs of food addiction.

- Women in similar mental health categories were nearly three times more likely.

Physical Health:

- Men with poor physical health were three times more likely to be addicted to ultra-processed foods.

- Women in poor physical health were nearly twice as likely.

Social Isolation:

- Both men and women who said they felt isolated some of the time or often were three times more likely to be addicted compared to those who didn’t report loneliness.

The researchers note that people who view themselves as overweight may be particularly vulnerable to “health-washed” processed foods — those marketed as “low-fat,” “high-protein,” or “low-calorie” but still designed to trigger cravings.

Why This Generation Stands Out

The adults now in their 50s and early 60s are part of a unique historical window. They’re the first generation to have lived most of their lives in a food environment dominated by processed and packaged products.

From school cafeterias to grocery shelves, ultra-processed foods became the norm during their formative years. This exposure may have rewired their relationship with food — creating long-term vulnerabilities to craving and overconsumption.

Researchers suggest that there may be critical developmental periods in life when exposure to ultra-processed foods makes the brain more susceptible to addiction-like behaviors later on. If that’s true, the situation could worsen for younger generations who are growing up surrounded by these products from birth.

Future Generations at Even Greater Risk

Today’s children and teenagers consume even higher proportions of calories from ultra-processed foods than middle-aged adults did when they were young. If current trends continue, future generations could face even higher rates of food addiction later in life.

The study’s lead researcher, Ashley Gearhardt, who directs the University of Michigan’s Food and Addiction Science & Treatment Lab, emphasized that early intervention could be crucial. Just as we recognize critical periods for preventing alcohol or nicotine addiction, understanding and addressing ultra-processed food dependence early could make a major difference across a lifetime.

The Science Behind Food Addiction

Food addiction is still a controversial concept in science, but research continues to build evidence that some foods can trigger brain responses similar to addictive drugs. Highly processed foods — especially those combining refined carbs, fats, and flavor enhancers — activate the dopamine reward system, leading to a cycle of craving and reinforcement.

Studies using brain imaging have shown that eating sugary or fatty processed foods can light up the same brain regions activated by substances like cocaine or nicotine. While this doesn’t mean food is “as addictive” as drugs, it suggests that the same biological systems are being engaged.

The mYFAS 2.0 scale used in this study captures these addiction-like patterns. Questions include whether someone eats more than intended, feels unable to cut down, experiences withdrawal (such as irritability or headaches when cutting out certain foods), or continues to overeat despite knowing it’s harming their health.

Health Consequences of Ultra-Processed Foods

Beyond addiction, research over the last decade has made clear that ultra-processed foods are linked to numerous health problems. Large studies across multiple countries have found strong associations between high UPF consumption and:

- Obesity and metabolic syndrome

- Type 2 diabetes

- Heart disease and hypertension

- Depression and anxiety

- Cognitive decline and premature death

In one long-term study from France (the NutriNet-Santé cohort), every 10% increase in UPF intake was linked to a 14% higher risk of all-cause mortality. These findings reinforce what public health experts have been warning for years — that industrially processed foods aren’t just “junk” food; they’re biochemically designed to override normal appetite control.

Why the Concept of Food Addiction Matters

Some critics argue that calling it “addiction” is too strong. But researchers like Gearhardt and others believe the label is useful because it validates people’s real struggles with compulsive eating and helps shift the blame away from willpower.

When people say they feel “out of control” around certain foods — especially cookies, chips, or fast food — they’re often describing biological and psychological processes similar to substance dependence. Understanding this may lead to more compassionate and effective interventions, focusing on environmental change and public policy, not just personal restraint.

The Bigger Picture

This new research adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that ultra-processed foods are more than just unhealthy — they’re habit-forming.

For the generation that first grew up with them, the consequences are now coming into full view. But it’s not too late to act. Reducing exposure, improving food literacy, and encouraging whole, minimally processed foods can help undo some of the damage.

And for younger generations — who are consuming more processed foods than ever — this study serves as an early warning. If we continue on this path, food addiction could become one of the defining public health challenges of the coming decades.

Research Reference:

Ultra-processed food addiction in a nationally representative sample of older adults in the USA – Addiction Journal (DOI: 10.1111/add.70186)