Ancient Jordan Mass Grave Reveals the Human Impact of the World’s First Known Pandemic

Archaeologists and scientists are uncovering new evidence from northern Jordan that brings us closer than ever to understanding how the first known pandemic in human history affected real people living in ancient cities. At the center of this discovery is a mass grave found in the ancient city of Jerash, once known as Gerasa, dating back to the time of the Plague of Justinian between 541 and 750 CE. What makes this site remarkable is that it is the first mass burial from this pandemic to be confirmed both archaeologically and genetically, offering rare insight into how a deadly disease reshaped society during the Byzantine era.

A Pandemic That Changed the Ancient World

The Plague of Justinian is widely regarded as the earliest recorded pandemic and one of the most devastating disease outbreaks in history. It spread across the Mediterranean world, parts of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. Historical sources describe cities overwhelmed by illness, labor shortages, economic collapse, and repeated waves of death over nearly two centuries.

Until now, much of what historians knew about this pandemic came from written accounts and genetic traces found in isolated burials. Large-scale physical evidence of how people were buried during the crisis remained uncertain. The discovery in Jerash changes that.

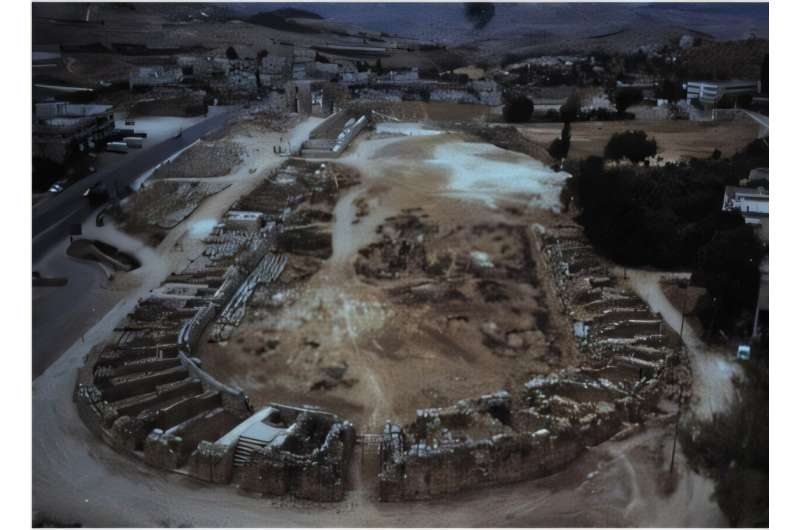

The Jerash Mass Grave and Where It Was Found

The mass grave was discovered inside the ancient hippodrome of Jerash, a large civic structure that once hosted public events and gatherings. By the time of the plague, the hippodrome had been abandoned. Archaeological evidence shows that during the height of the outbreak, this space was repurposed as an emergency burial ground.

Researchers identified hundreds of human remains, all deposited rapidly within a very short time frame. The bodies were placed directly on top of layers of broken pottery debris, with no signs of traditional burial rituals. This confirms that the city was dealing with an acute mortality crisis, where normal funerary practices were no longer possible.

Unlike typical cemeteries that grow gradually over decades, this burial represents a single mortuary event, likely carried out over just a few days.

Confirming the Cause of Death Through DNA

One of the most important aspects of this discovery is how the cause of death was confirmed. Scientists extracted ancient DNA from teeth found at the site and identified the presence of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for bubonic plague.

This genetic confirmation directly links the Jerash mass grave to the Plague of Justinian. While earlier studies had identified Yersinia pestis in isolated remains from other regions, Jerash is the first site where a mass burial has been conclusively tied to this pandemic using both genetic and archaeological evidence.

Who Were the People Buried There?

The individuals buried at Jerash came from diverse backgrounds. Osteological analysis shows a mix of ages and sexes, indicating that the plague did not target a specific group. Instead, it swept through the population indiscriminately.

What stands out is evidence suggesting that many of those buried were part of a mobile population. Isotopic and biological data indicate that some individuals did not grow up locally, reflecting the movement of people through trade, migration, and empire-wide connections common in the Byzantine world.

Under normal circumstances, this mobility is difficult to detect because migrants often settle and blend into local communities over generations. However, the sudden crisis of the plague brought these individuals together in death, making long-term patterns of movement visible in a single archaeological moment.

Rethinking Life and Movement in Ancient Cities

This finding helps resolve a long-standing puzzle in archaeology. On one hand, historical records and genetic data show extensive movement and mixing across the ancient Mediterranean. On the other hand, most cemeteries suggest that people lived and died close to where they were born.

The Jerash mass grave shows that both realities can exist at the same time. Daily life may appear local and stable, but cities like Jerash were deeply connected to broader regional networks. During a pandemic, those hidden connections became suddenly visible as vulnerable populations were concentrated in emergency burial sites.

A Human-Centered Approach to Studying Pandemics

This research goes beyond identifying a pathogen. The goal was to understand what pandemic death looked like inside a real city and how disease intersected with everyday life. By combining biological evidence with archaeological context, researchers were able to reconstruct how people lived, moved, and died during the crisis.

The study highlights that pandemics are not just medical events. They are also social, environmental, and civic crises that reveal inequalities, vulnerabilities, and patterns of human behavior.

Why the Discovery Matters Today

The Jerash mass grave provides direct evidence that the Plague of Justinian caused large-scale urban mortality, supporting historical accounts that describe widespread devastation. It also shows how cities responded when overwhelmed, repurposing public spaces and abandoning established rituals to cope with mass death.

There are clear parallels with modern pandemics. Dense populations, global movement, trade networks, and environmental pressures all played a role in the spread of disease in antiquity, just as they do today. Studying how ancient societies experienced and responded to pandemics helps us better understand the long-term impact of such events on human history.

Understanding the Plague of Justinian in Context

The Plague of Justinian is believed to have originated in regions connected by trade routes linking Africa, Asia, and the Mediterranean. It recurred in waves for nearly 200 years, contributing to population decline and economic strain across the Byzantine Empire.

Many historians believe the pandemic played a role in weakening imperial structures and reshaping political and social systems across the region. Discoveries like Jerash add physical evidence to these broader historical interpretations.

Jerash as a Window Into the Past

Jerash is one of the best-preserved Greco-Roman cities in the Middle East, often referred to as the Pompeii of Jordan. Its well-documented urban layout makes it an ideal site for studying how crises affected daily life. The mass grave found in the hippodrome adds a deeply human dimension to the city’s history, reminding us that behind monumental architecture were communities vulnerable to forces beyond their control.

Moving Forward With Ancient Pandemic Research

This study represents the third in a series of scholarly papers examining the Plague of Justinian. Earlier work focused on identifying the pathogen itself, while this research shifts attention to the people who lived through the pandemic and how their city responded.

As techniques in ancient DNA analysis and bioarchaeology continue to improve, more discoveries like this may emerge, further reshaping our understanding of pandemics in the ancient world.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2026.106473