How Computerized Machine Tools Reshaped American Manufacturing and What This Means for Today’s AI Wave

In the early 1970s, a major technological shift quietly began on American factory floors. Machines that once relied on the steady hands of skilled machinists—lathes, drill presses, milling machines—started operating through computer numerical control, or CNC. This change transformed traditional tools into automated systems capable of carrying out complex tasks with precision and consistency, all guided by programmed instructions rather than manual labor.

A new study led by economist David Clingingsmith from Case Western Reserve University revisits this period to understand how this earlier wave of computer-driven automation unfolded and how workers managed to adapt. With AI now poised to automate large portions of white-collar and service work, researchers believe that the CNC era offers important clues about how the workforce might respond to modern technological disruption.

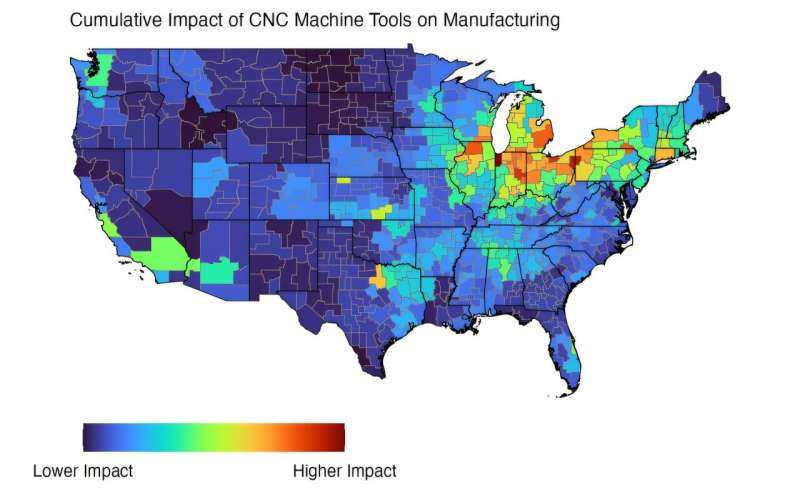

The study, developed with researchers from Yale and Brandeis and published in the Review of Economics and Statistics, tracks how CNC technology spread across industries from 1970 to 2010 and measures how deeply different regions were affected. The team then examined long-term outcomes for productivity, job levels, worker retraining, and regional economies. Their data offers a detailed look at what happens when a foundational technology reshapes entire sectors—not just for a few years, but for decades.

One of the most striking insights is that workers adapted far more successfully than many assume. Instead of mass displacement and permanent job loss, the CNC transition prompted widespread career shifts and retraining efforts. Many workers moved out of heavily automated metalworking industries and into other types of manufacturing such as plastics or wood products—fields where computers had not yet taken over. Others transitioned into wholesale and retail work. Unions, which represented about 45% of metalworkers in the 1970s, played an important role in negotiating protections, easing transitions, and supporting retraining opportunities.

The research shows that CNC automation increased labor productivity by about 7%, confirming that automated tools made factories more efficient. However, production employment fell by 12%, and the burden of these losses was not evenly distributed. Job losses were concentrated among mid-skilled, non-union workers with a high school education or less. For high school dropouts, employment declined by 24% in affected regions. In contrast, employment for college graduates increased by 17%, showing how newly automated environments rewarded higher education and programming skills.

Workers did not simply vanish from the labor market. Many sought education to remain competitive, and colleges expanded degree programs in CNC-related fields, computer-aided manufacturing, and engineering. These retraining programs helped workers gain the specialized skills needed to operate, maintain, and program the new machines replacing their old jobs. Still, the study warns that while transitions were possible, they were not painless. When workers lose long-standing, well-paid roles, their new career paths often place them on lower long-term income trajectories.

The rise of CNC tools also reshaped the geographic landscape of American manufacturing. The regions hit hardest included the Rust Belt and what Clingingsmith refers to as the “aircraft manufacturing archipelago”—a cluster including Southern California and areas around Seattle. These regions, which had heavy concentrations of metalworking and aerospace production, experienced rapid technological change and shifting labor demands. Interestingly, the same clustering that once made these regions vulnerable could now position them as potential hubs for renewed, high-value manufacturing—if investments in worker skills and technical infrastructure continue.

This historical experience matters today because AI is creating a new era of workplace automation, one that extends beyond factories and into law, finance, customer service, and other knowledge-based professions. Unlike CNC technology—which primarily affected middle-income blue-collar workers—AI has the potential to reshape jobs held by workers with advanced degrees and specialized training. This marks a broader and potentially more disruptive shift.

Researchers caution that the conditions that made adaptation possible during the CNC transition may not exist at the same scale today. Union membership has declined sharply, reducing structural support for workers navigating layoffs or retraining. Industries are less geographically concentrated, making coordinated regional responses more difficult. The speed of technological change has increased, leaving workers less time to adjust. And while CNC tools automated specific tasks, AI may automate whole decision-making processes, expanding its impact.

Still, the CNC example demonstrates that workers can adapt to technological change when clear retraining pathways, supportive institutions, and alternative job opportunities are available. The challenge now is ensuring similar support systems exist for the AI era. Policymakers and educators may need to rethink how training programs, community colleges, and industry partnerships can prepare workers for jobs that require more analytical skills, oversight of automated systems, and technical literacy.

To add some broader context, the CNC shift wasn’t the first or last time automation changed how Americans work. Earlier waves included electrification, assembly lines, and mechanized agriculture. Each time, productivity rose and labor markets eventually adjusted, though not always smoothly. With CNC specifically, the biggest change was the shift from manual precision to computer-guided precision, allowing manufacturers to increase consistency, reduce errors, and scale production more efficiently. Today, digital fabrication tools like 3D printers build on this legacy, further blending software and physical production.

Meanwhile, AI represents a different kind of automation—one that targets information processing rather than physical tasks. While CNC machines replaced the hands of machinists, AI has the potential to replace or augment the decision-making and analysis work of white-collar professionals. This shift might require broader retraining strategies that extend beyond technical certifications and into areas like critical thinking, data literacy, and human-AI collaboration.

It’s also useful to understand how technological transitions can create entirely new job categories. CNC tools led to roles in machine programming, maintenance, systems integration, and digital manufacturing. Similarly, AI is expected to create opportunities in model auditing, AI safety, data engineering, and augmented decision support. But history shows that newly created jobs often require higher skills than the jobs lost, which makes accessible education and retraining essential.

The CNC transition emphasizes another point: clusters matter. When industries concentrate in certain regions, workers, companies, and institutions share knowledge and adapt faster. This is why Silicon Valley became a tech powerhouse and why aerospace thrived in Southern California. As AI reshapes industries, regions with strong research institutions, technical colleges, and innovation networks may become new centers of growth—if they invest in the right skills.

Overall, the study provides a grounded, data-driven perspective on the long-term effects of automation. It shows that while technological change can be disruptive, it doesn’t inevitably lead to widespread unemployment. What matters most is how workers, institutions, and industries respond. The CNC era offers a blueprint—but also a warning. Adaptation is possible, but it requires deliberate planning, supportive infrastructure, and investments in people, not just machines.

Research Reference:

https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.a.287