How Researchers Figured Out the PCAOB’s Secretive Process for Selecting Audit Inspections

The year 2024 was a milestone for the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, or PCAOB. It marked 20 years since the launch of its inspection program, and it also turned out to be a record-breaking year for enforcement. The board finalized 51 disciplinary actions and imposed $35.7 million in monetary penalties, the highest total in its history. Yet despite its growing influence, one key part of the PCAOB’s work has remained largely hidden from public view: how it decides which audits to inspect.

A new academic study has now offered one of the clearest looks yet into that decision-making process. The research does not rely on leaks or insider tips. Instead, it uses publicly available data in a creative way to reverse-engineer how the PCAOB appears to choose its inspection targets. The result is a detailed, data-driven picture of a regulator that operates under tight resource constraints, prioritizes risk signals, and combines structured judgment with a degree of randomness.

Why PCAOB Inspections Matter So Much

The PCAOB is a non-profit oversight body created after major accounting scandals in the early 2000s. Its core job is to oversee auditors of publicly traded companies in the United States. These auditors are responsible for ensuring that corporate financial statements are accurate and comply with accounting standards.

In theory, every audit could be inspected. In practice, that is impossible. Each year, more than 4,000 public companies undergo audits, and the PCAOB simply does not have the manpower or budget to review them all. In fact, for U.S. audit firms that are inspected annually, as few as 2% of their engagements are selected for inspection in any given year.

That makes the selection process incredibly important. Being chosen for inspection can lead to findings of audit deficiencies, reputational damage for audit firms, and in some cases serious enforcement actions and fines. At the same time, the PCAOB deliberately keeps its selection criteria vague to avoid giving auditors a playbook for gaming the system.

A Rare Peek Behind the Curtain

The new study was led by Min Shen, an associate professor of accounting at George Mason University and a Philip G. Buchanan Fellow at its Costello College of Business. She worked alongside Daniel Aobdia of Penn State University, Edward Xuejun Li of Baruch College, and K. Ramesh of Rice University. Their paper was published in the journal Management Science.

Rather than speculating about the PCAOB’s motives, the researchers focused on a straightforward question: does the inspection program align with the PCAOB’s mission to improve audit quality? To answer that, they needed evidence of which companies were inspected and when, something the PCAOB does not publicly disclose in detail.

Their solution was both clever and unconventional.

Using SEC Log Data to Track PCAOB Activity

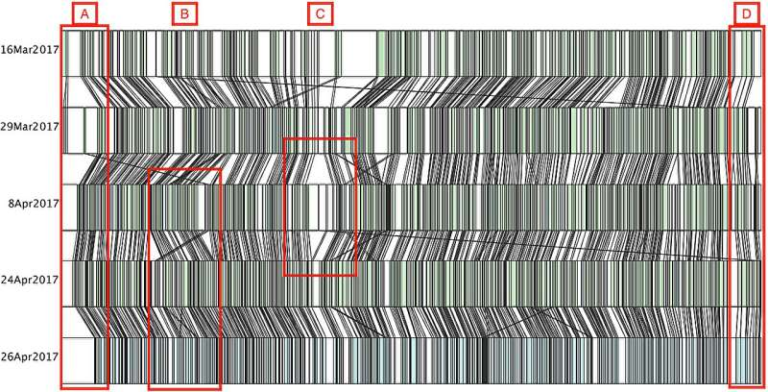

The researchers relied on SEC EDGAR log files, which record IP addresses that access corporate filings on the SEC’s EDGAR system. These logs cover the period from 2007 to 2016. By cross-referencing the IP addresses with data from the American Registry for Internet Numbers, the team was able to identify which IP addresses were affiliated with the PCAOB.

Once that link was established, they could see which company filings the PCAOB was viewing and when. The final dataset included 46,101 observations spanning auditors, issuers, and multiple years.

Of course, simply accessing a filing does not automatically mean an inspection is happening. The PCAOB could be monitoring companies for other reasons, such as enforcement or general oversight. To address this concern, the researchers used two independent verification methods.

Confirming the Link to Inspections

First, they examined triennial audit firms, which are inspected only once every three years. They compared PCAOB search activity during inspection years versus non-inspection years. The difference was striking. During inspection years, search activity increased by 61% to 132%, strongly suggesting that the observed EDGAR access was tied directly to inspections.

Second, they analyzed transcripts from the 2019 United States vs. David Middendorf trial. Middendorf, a former senior leader at KPMG, was involved in illegally obtaining confidential PCAOB inspection-selection information between 2015 and 2017 from former PCAOB employees. The trial transcripts named 40 KPMG client companies that were confirmed to be on the PCAOB’s inspection list. These companies also appeared in the researchers’ dataset, providing further validation.

Together, these checks gave the researchers high confidence that they were observing actual inspection-related behavior, not random browsing.

What Triggers PCAOB Attention

With this foundation in place, the team analyzed what characteristics made certain companies and audits more likely to attract PCAOB scrutiny.

One clear pattern involved company size. Large, high-profile issuers such as Meta, JPMorgan Chase, and Apple were inspected frequently, often on an annual basis. These companies carry enormous market impact, so audit failures would have far-reaching consequences.

Another strong signal was auditor change, especially when a company switched from a Big Four audit firm to a non-Big Four firm. Such changes are relatively rare and often suggest underlying issues, making them a natural red flag for regulators.

Executive turnover also mattered, but not all turnover was treated equally. CEO turnover did not significantly increase inspection likelihood, likely because CEOs leave for many reasons unrelated to accounting. CFO turnover, however, stood out as a meaningful trigger. Since CFOs are directly responsible for financial reporting and internal controls, their departure can signal potential accounting or auditing problems.

Building a Predictive Model Without Insider Data

The researchers then took their analysis a step further by building a predictive model. The goal was to estimate the probability that a specific Big Four audit engagement would be inspected in a given year.

Crucially, this model used only publicly available data. It did not rely on SEC log files or any insider information. Despite that limitation, the model’s predictions closely matched observed PCAOB search activity.

This suggests that the PCAOB’s selection process, while confidential, is not arbitrary. It appears to rely heavily on observable risk indicators that are already visible to the public.

That said, the model was not perfect. Some audits are selected randomly by design, and there may be additional signals that future researchers could incorporate. Random selection is intentional, as it prevents audit firms from becoming too comfortable or predictable.

A Regulator Under Constraints

Taken together, the findings portray the PCAOB as a regulator that operates cautiously and reactively. Rather than continuously scanning every audit engagement, the board appears to respond to specific events, such as CFO turnover or auditor changes, before digging deeper into SEC filings.

This approach makes sense given the PCAOB’s limited resources and political sensitivities. Monitoring every issuer in real time would require far more funding and staff than the organization currently has.

The research also raises interesting questions about the future. Advanced analytics and AI tools could potentially help the PCAOB monitor a broader range of audits and detect risk signals earlier, shifting the balance from reactive oversight to more proactive supervision.

Understanding the Broader Role of PCAOB Inspections

Beyond this specific study, PCAOB inspections play a central role in shaping audit behavior. Audit firms know that inspections can uncover deficiencies and lead to enforcement actions, so the mere risk of inspection influences how audits are planned and executed.

Academic research has shown that higher inspection risk is often associated with greater audit effort, improved documentation, and, in some cases, fewer financial restatements later on. In that sense, inspections function not just as a policing mechanism but as a deterrent and quality-control tool.

Why This Research Matters

What makes this study especially valuable is that it demonstrates how public data can be used to shed light on opaque regulatory processes. Without revealing confidential methods, the researchers were able to show that the PCAOB’s inspection program is broadly aligned with its mission and focused on areas of elevated risk.

For investors, audit committees, and regulators, these insights help clarify how oversight actually works behind the scenes. For auditors, it reinforces the idea that visible risk signals matter, even if the exact inspection formula remains unknown.

Research Paper Reference:

https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2024.08084