How the 2008 Great Recession Changed How Americans See Their Social Class for Years

The way people see themselves in society is not just about how much money they make or what job they hold. It is also about class identity—the personal sense of where one stands economically and socially compared to others. A new psychological study shows that the 2008 Great Recession didn’t just damage bank accounts and job prospects, it also permanently shifted how millions of Americans viewed their own social class.

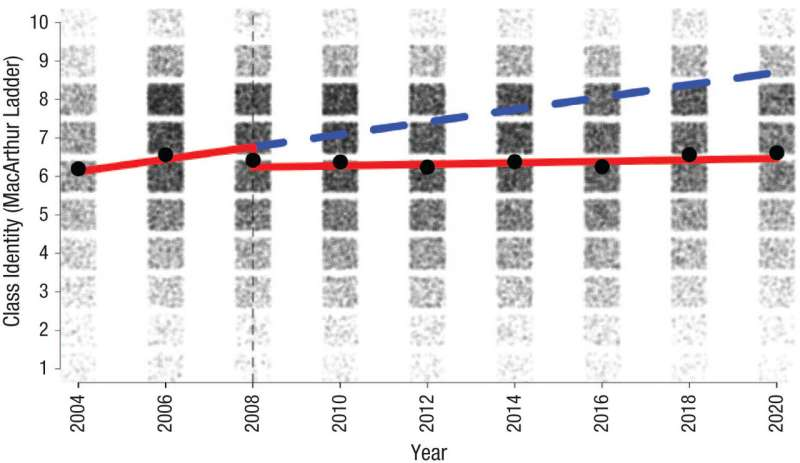

This research, published in Psychological Science in 2025, reveals that the Great Recession led many Americans to identify with a lower social class, and this shift lasted for years rather than fading once the economy began to recover.

What the Study Looked At

The study was led by Stephen Antonoplis, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside. His goal was to understand whether large-scale economic events, like the Great Recession, could cause long-term changes in how people perceive their social position.

Most earlier research suggested that class identity is relatively stable over time. When changes were observed, they were usually short-lived and often caused by experimental setups rather than real-world events. Antonoplis wanted to test something different: What happens to class identity when a massive economic shock affects an entire country?

To answer this, the research team analyzed four large, long-running datasets that collectively tracked about 165,000 Americans over several decades. These datasets included repeated measures of how individuals described their own class identity before, during, and after the 2008 recession.

A Long-Lasting Drop in Class Identity

The results were clear and striking. During the Great Recession, Americans began identifying with lower social classes, and this shift persisted for years, even after traditional economic indicators improved.

This finding challenges the idea that class identity is fixed or only temporarily influenced. Instead, it suggests that major historical events can reshape how people see themselves in society for the long term.

Importantly, the study did not claim that everyone actually lost the same amount of income or material resources. Instead, it focused on self-perception, which can diverge significantly from objective financial data.

Why This Study Is Different from Earlier Research

Much of the earlier work on class identity relied on tools like the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status. This scale presents people with a ladder of ten rungs, where the top represents the most resources (money, education, job quality) and the bottom represents the least.

Researchers sometimes manipulated how participants thought about the ladder. For example, participants asked to compare themselves only to the lowest rung tended to place themselves higher, while those thinking only about the top rung placed themselves lower. However, these effects typically faded within minutes.

Antonoplis’ research showed something very different. The changes linked to the Great Recession were not temporary framing effects. They were enduring psychological shifts, measurable across years and visible in multiple independent datasets.

Class Identity Is Not the Same as Income

One of the most interesting aspects of the study is the clear distinction between objective resources and subjective identity. Class identity is deeply personal and does not always align with income.

Some individuals with relatively high incomes still identify as lower class, while others with fewer resources may not. The study deliberately focused on how people see themselves, not how economists might classify them.

This matters because class identity has been linked in previous research to physical health, emotional well-being, political attitudes, and overall outlook on society. People who identify with higher classes tend to report better health and more optimism, while those identifying with lower classes often experience greater stress and insecurity.

The Role of Media and Public Messaging

Beyond direct financial losses, the study suggests that media coverage during the Great Recession may have amplified feelings of downward mobility. News headlines at the time frequently emphasized long-term decline, uncertainty, and fear about the future.

Stories about rising unemployment, shrinking opportunities, and diminished prospects for children were widespread across major media outlets. This constant exposure to threatening economic narratives may have reinforced the idea that people’s social standing was slipping permanently, even if their personal circumstances had not changed dramatically.

According to the research, this broader social environment likely played a role in shaping collective perceptions of class.

Health, Stress, and Psychological Consequences

The findings also point to a possible explanation for why the Great Recession was associated with worsening health outcomes for many Americans. While financial strain is an obvious factor, perceived loss of status may be another important pathway.

Feeling lower in the social hierarchy can increase chronic stress, anxiety, and feelings of insecurity. Over time, these psychological pressures can translate into real physical health problems.

Although this particular study did not directly measure health outcomes, it opens the door for future research examining how shifts in class identity affect long-term mental and physical health.

Political and Social Ripple Effects

Changes in class identity may also help explain political shifts in the United States since 2008. Class identity has been linked to voting behavior, trust in institutions, and attitudes toward social change.

If large segments of the population began seeing themselves as worse off or more vulnerable, this could influence political polarization, skepticism toward elites, and support for populist movements. The study does not make direct claims about politics, but it highlights class identity as a potentially important factor in understanding post-recession social dynamics.

Why This Matters Beyond the United States

The Great Recession was not limited to the U.S. It triggered economic downturns in many other countries, meaning the psychological effects observed here may have global relevance.

Understanding how economic crises shape identity can help policymakers, researchers, and the public better prepare for future downturns. Awareness of these effects may also help individuals recognize that feeling “lower class” after a recession is not just a personal failure, but a common psychological response to widespread economic disruption.

Connections to Today’s Economic Anxiety

The study may also shed light on more recent phenomena, such as the so-called “vibecession”—a term used to describe persistent feelings of economic insecurity despite relatively strong economic indicators.

Issues like inflation, rising living costs, and intense media focus on economic uncertainty may be recreating some of the same psychological conditions seen during the Great Recession. This raises important questions about how perception, not just numbers, shapes economic well-being.

A Clear Takeaway

The key takeaway from this research is simple but powerful: economic crises don’t just affect wallets—they reshape identities. The Great Recession left a lasting psychological imprint, lowering how Americans viewed their place in society long after the economy began to recover.

By recognizing these effects, society can better understand the full cost of recessions and possibly reduce their long-term harm in the future.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976251400338