How University Patenting Policies Are Shaping the Future of Scientific Research

Universities have long wrestled with a fundamental question: should scientists focus purely on advancing knowledge, or should they also be encouraged to turn discoveries into practical technologies? A major new study published in Science suggests that this long-standing divide may be misguided. According to the research, scientists who actively engage in both academic publishing and patenting are not weakening “pure” science at all. In fact, they are strengthening it.

The study offers one of the most comprehensive looks to date at how scientific discovery and technological invention interact inside universities. Its findings challenge traditional academic norms and raise important questions about tenure policies, research funding, and how innovation actually happens.

The Core Finding: Publishing and Patenting Reinforce Each Other

At the heart of the study is a simple but powerful insight: researchers who both publish papers and file patents produce work that is more novel, more influential, and more widely cited than researchers who stick to only one of those activities.

The researchers refer to these individuals as Pasteur’s quadrant researchers, a term inspired by Louis Pasteur, who famously combined fundamental scientific inquiry with practical applications. Instead of viewing science and invention as separate or sequential steps, these researchers operate in both worlds at the same time.

This directly challenges the traditional linear model of innovation, which assumes that scientists should first conduct basic research and only later hand their findings over to engineers or companies for application. The evidence in this study suggests that thinking about real-world use during the research process can actually improve the quality of scientific work itself.

A Massive Dataset Spanning Nearly Five Decades

One reason this study stands out is its scale. The research team linked all scientific publications and U.S. patents from 1976 onward, creating a dataset that includes nearly 700,000 individuals who have both published academic research and filed patents.

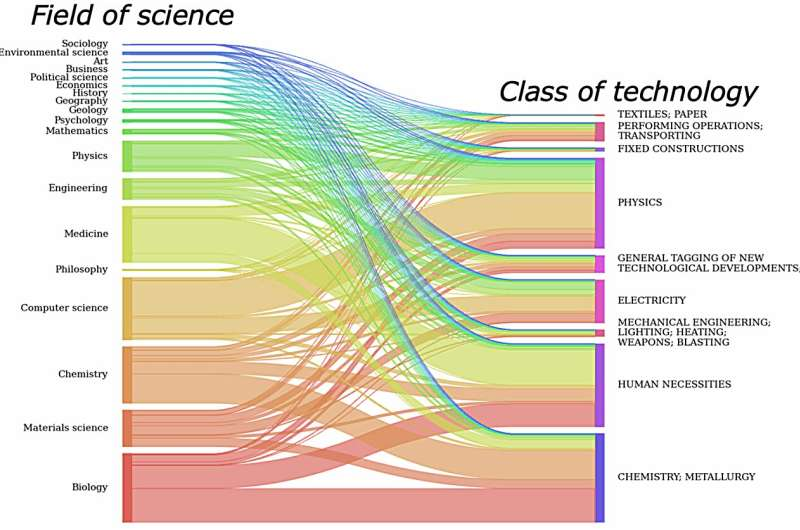

This dataset allowed the authors to examine patterns across:

- Multiple scientific fields

- Different universities and institutions

- Long time periods, from the late 1970s to the 2010s

By analyzing both citation impact and novelty metrics, the study provides robust evidence that the combination of science and invention is associated with stronger outcomes on both fronts.

Why Combining Science and Technology Boosts Creativity

One of the most interesting aspects of the findings is why this combination works so well. According to the study, working on applied problems exposes scientists to new constraints, challenges, and perspectives that can spark creative breakthroughs.

Applied research can prevent scientists from becoming overly attached to narrow theoretical approaches that are not yielding results. At the same time, scientists trained in fundamental research are uniquely positioned to recognize unexpected patterns or anomalies that emerge during technological development.

Historically, many major scientific discoveries have emerged from this kind of cross-pollination. For example, research aimed at improving microwave communication technology unexpectedly led to the discovery of cosmic background radiation, a cornerstone of modern cosmology.

Early-Career Researchers Benefit More Than Expected

One of the most striking findings relates to early-career scientists. University administrators and tenure committees have often worried that patenting too early might distract young researchers from building a strong publication record.

The data suggests otherwise.

The researchers carefully matched scientists by field, institution, and number of early publications. They found that scientists who patented within their first five years had higher long-term research impact, even when they initially published slightly fewer papers.

In fact, early-career researchers who patented ended up with about 25% more lifetime citations than their peers who did not patent early. This suggests that while patenting may take time, the type of applied research involved often leads to bigger and more influential breakthroughs in the long run.

Growth of Pasteur’s Quadrant Researchers Over Time

The study also reveals how dramatically this type of researcher has grown over the past few decades. Between 1980 and 2016, the number of scientists who both publish and patent increased by approximately 350%.

A key driver of this growth was the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, which allowed universities and small businesses to retain intellectual property rights for inventions arising from federally funded research. This policy shift fundamentally changed how universities approached technology transfer and commercialization.

By 2016:

- Pasteur’s quadrant researchers made up about 14% of all inventors

- They represented roughly 4% of all scientists

While still a minority, their influence on high-impact research is disproportionately large.

Changing Demographics and Geographic Concentration

The study also sheds light on who these researchers are and where they work.

One notable trend is the rise in female representation among dual-purpose researchers. In 1980, women accounted for only about 5% of this group. By 2016, that figure had grown to more than 25%, reflecting broader changes in academic participation and innovation ecosystems.

Geographically, however, these researchers are highly concentrated. By 2016, nearly half of all Pasteur’s quadrant researchers were located in the top 1% of U.S. counties by economic output. This highlights the strong connection between wealth, research infrastructure, and opportunities to move between science and technology.

Implications for University Policies and Tenure Decisions

The findings raise serious questions about how universities evaluate faculty performance. In many institutions, patenting and entrepreneurship are still viewed as distractions from “real” academic work.

The evidence suggests that such views may be counterproductive. If patenting is associated with more impactful science, then tenure and promotion criteria that penalize applied research could be discouraging exactly the kind of work that leads to major breakthroughs.

Some universities are already moving in a new direction. Initiatives like Promotion & Tenure—Innovation & Entrepreneurship (PTIE) aim to formally recognize applied research, patents, and startup activity as legitimate academic contributions. The University of California system adopted such a policy in 2021, explicitly acknowledging innovation and entrepreneurship in faculty evaluations.

Important Caveats: Correlation, Not Proof of Causation

The authors are careful to note that their findings are correlational, not definitive proof that patenting causes better science. It is possible that certain personality traits, institutional cultures, or funding environments encourage both patenting and high-quality research.

However, the consistency of the patterns across fields, institutions, and decades makes the results difficult to dismiss. At the very least, the study strongly challenges the idea that applied research undermines scientific excellence.

Rethinking the Boundary Between Science and Innovation

Taken together, the findings suggest that the old boundary separating scientists from inventors may be holding both groups back. Researchers who move fluidly between publishing papers and filing patents are not diluting their contributions. They are amplifying them.

For universities, funding agencies, and policymakers, this research offers a clear message: encouraging scientists to think about application while pursuing fundamental questions may be one of the most effective ways to advance both knowledge and innovation.

Research Paper:

Scharfmann, E., Marx, M., Fleming, L. et al. Pasteur’s quadrant researchers bring novelty and impact to publishing and patenting. Science (2025).

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adx3736