NYC’s Intensive Housing Remediation Effort Cut Violations in Half but Health Improvements Have Not Yet Followed

New York City has been working for years to repair some of its most distressed privately owned residential buildings, and a new study offers one of the clearest looks yet at what these efforts have achieved. The research, conducted by Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, examined the long-running Alternative Enforcement Program (AEP)—the city’s most assertive attempt to force repairs in low-quality private housing. The findings tell a story that is both encouraging and sobering: while hazardous housing violations dropped dramatically, these improvements did not translate into immediate changes in residents’ health care usage.

The study appears in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management and focuses on a segment of housing that often receives far less attention than public housing—privately owned buildings that house thousands of low-income New Yorkers. These are places where landlord oversight is often weaker, maintenance is inconsistent, and tenants may struggle with longstanding hazards. Because research in this area has been limited, this study provides rare insight into how housing remediation intersects with real-world health outcomes.

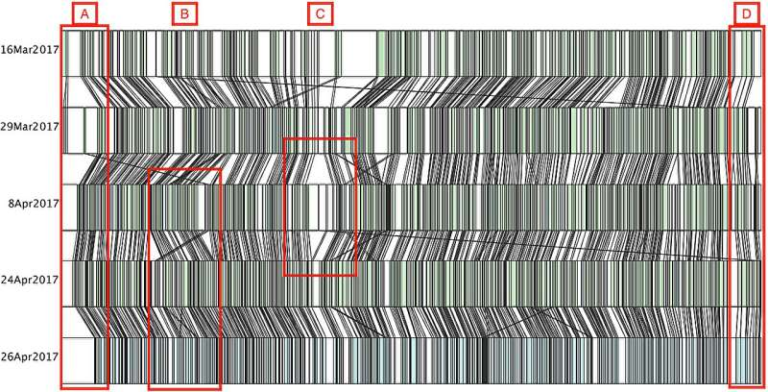

The AEP was created under the NYC Safe Housing Law of 2007 and is written into the City Charter. Each year, the program identifies the 250 most distressed residential buildings in the city. Once selected, landlords face strict deadlines: within four months, they must correct all heat and hot water violations and repair at least 80 percent of immediately hazardous conditions. These include serious mold growth, widespread pest or rodent infestations, peeling lead paint, water leaks, broken windows or fixtures, and other problems known to put residents’ health at risk. If landlords refuse or fail, the city can intervene directly by completing the repairs itself and placing a lien on the property, along with fines or legal action.

City reports from the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) consistently show that AEP leads to major improvements in building conditions. Even in buildings owned by some of New York’s most neglectful landlords, violation correction rates are high. The Columbia study confirms this, finding that hazardous violations in AEP-treated buildings were cut by roughly half. For a program dealing with decades of disinvestment, that level of improvement is substantial.

But when the researchers examined how these building improvements affected health care utilization among residents, the results were unexpectedly flat. The study followed 48,151 Medicaid enrollees living in AEP-eligible buildings between 2007 and 2018. Out of those, 24,294 individuals were included in the final data set—14,974 residents in untreated buildings and 9,320 residents in buildings that underwent remediation. Using Medicaid eligibility and claims data from 2007 through 2019, the researchers looked at total health care spending, emergency department visits, and medical visits related to conditions commonly linked to poor housing, such as respiratory issues, injuries, and anxiety.

Despite the sharp reduction in hazardous violations, the study found no meaningful short-term changes in health care utilization. Emergency department visits did not decrease, overall health care spending did not budge, and visits related to housing-associated conditions remained essentially unchanged. Even though residents were living in safer and more stable housing conditions, the improvements did not immediately appear in the data on how often they sought medical care.

This disconnect raises important questions. Housing and health are deeply intertwined, but the timeline between environmental improvements and health outcomes can be complicated. For instance, chronic respiratory problems or anxiety related to unstable housing may not diminish quickly, even when environmental triggers are reduced. Residents may also still be living in severely distressed buildings, because cutting half the violations in the city’s worst properties still leaves many hazards unaddressed. The researchers note that even after remediation, AEP buildings remain some of the most deteriorated in New York City, reflecting how difficult it is to fully reverse the effects of long-term neglect.

The results carry significant policy implications. Programs like Medicaid and Medicare have started experimenting with paying for housing-related services—such as ventilation improvements, pest management, or mold remediation—under the belief that improving living conditions could reduce future medical costs. The logic is straightforward: fewer hazards should mean fewer health problems and therefore fewer expensive medical interventions. But this study suggests that the expectation of immediate cost savings may not be realistic. Housing improvements remain critically important, but their health effects might take years to fully appear, particularly in severely distressed environments.

It’s also worth noting the broader context: across the United States, 42 percent of low-income households live in homes needing at least one major repair. Up to 20 percent of homes in low-income neighborhoods contain three or more serious hazards linked to health risks. In other words, New York’s challenges are not unique—they’re part of a national pattern where millions of people live with environmental conditions that quietly undermine their well-being.

To better understand the significance of this research, it helps to look more closely at the kinds of hazards the AEP prioritizes. Issues like mold, pests, rodents, and broken windows may seem minor on the surface, but they accumulate into chronic stressors. Mold spores worsen asthma symptoms, especially in children. Rodent infestations increase the risk of airborne contaminants and allergies. Leaks and water damage contribute to structural decay and air quality problems. Heat and hot water failures place tenants at physical risk, especially in winter. These conditions also create psychological strain, as tenants live with uncertainty and a reduced sense of safety in their own homes. By forcing repairs, the AEP aims to reduce these risks at their root.

So why might health systems data not show immediate change? One contributing factor is that many health effects are lagging indicators. Injuries from a broken stair may decline right away if the stair is fixed, but asthma triggered by years of mold exposure may take considerable time to stabilize. Another factor is that the improvements, while significant, do not completely transform living conditions. When violations are cut by 50 percent, the remaining 50 percent can still cause substantial harm. Full remediation often requires deeper, more expensive interventions than landlords are required or willing to make.

This study also underscores how complex the housing-health relationship truly is. Environmental improvements matter, but so does the social environment—stress levels, neighborhood conditions, landlord-tenant relationships, and economic stability. Housing quality is one piece of a much larger puzzle.

In the long run, the findings support the idea that more comprehensive remediation and ongoing follow-up may be necessary before measurable health improvements appear. Short-term data offers valuable insight, but the true benefits of safer housing may unfold over a much longer period. As cities and policymakers consider how to allocate resources, this study provides a grounding reminder: improving housing is essential, but expecting quick health care savings oversimplifies a much deeper issue.

Research Paper:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pam.70074