Push and Pull Cities’ Living Conditions and Job Quality Can Improve Human Mobility Models

Understanding why people move from one place to another has always been a central question in urban studies, economics, and population science. A new study published in PNAS Nexus takes a meaningful step forward by showing that where people live and the quality of jobs available play a far bigger role in human mobility than many traditional models have assumed. By weaving real-world inequalities into mathematical migration models, researchers have demonstrated that we can predict human movement more accurately and more realistically.

Rethinking How Human Mobility Is Modeled

For decades, scientists have relied on simplified mathematical frameworks to explain migration and commuting patterns. Two of the most widely used are the gravity model and the radiation model. The gravity model assumes that people are more likely to move to large cities and less likely to move long distances, treating population size and distance as the dominant factors. In this framework, bigger cities naturally exert more “pull” than smaller ones.

The radiation model took a different approach by focusing on opportunities rather than population alone. It estimates migration flows based on the number of opportunities available at a destination relative to those in surrounding areas. While this was a step forward, both models share a key limitation: they largely treat cities and regions as equal in quality.

In reality, that assumption rarely holds. Cities differ dramatically in terms of living conditions, safety, economic opportunity, and social stability. These differences influence not only whether people move, but also when, where, and how far they are willing to go.

Introducing Inequality Into Mobility Models

In the new study, researcher Maurizio Porfiri and his colleagues set out to address this gap. They extended the traditional radiation model by explicitly incorporating inequalities between locations. Instead of assuming that all opportunities are equivalent, the new model adjusts for factors that either attract or repel people.

These factors include:

- Conflicts and political persecution

- Natural hazards such as floods

- Income and wealth inequality

- Job quality and economic security

- Living conditions, including housing affordability and poverty levels

By accounting for these variables, the model captures both push factors (conditions that drive people away from a place) and pull factors (conditions that draw people in).

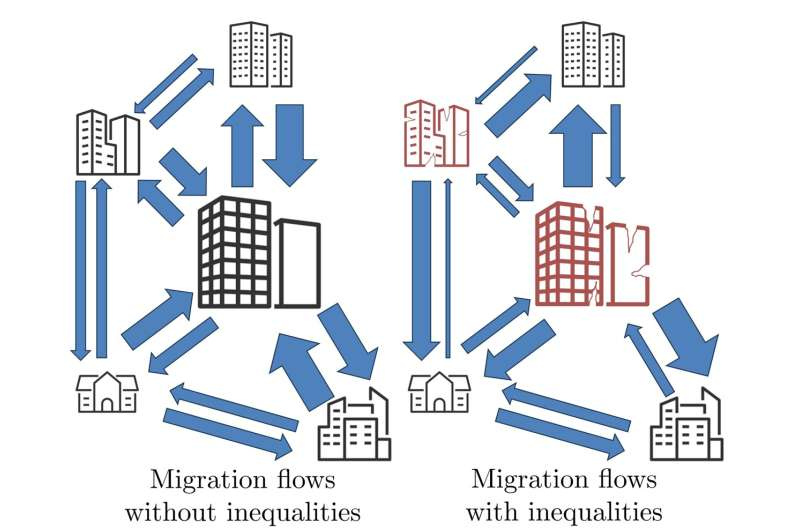

How Inequalities Reshape Movement Patterns

The study shows that inequalities can reshape migration flows in disruptive ways. A city with a large population might appear attractive under traditional models, but if it also has high poverty rates, unsafe living conditions, or unaffordable housing, its actual pull may be much weaker.

Conversely, smaller or less populous locations can become strong destinations if they offer better quality of life or more stable employment opportunities. By adjusting the perceived value of opportunities based on these realities, the new model reflects how people actually make decisions.

This shift is especially important in a world increasingly shaped by climate change, conflict, and economic polarization, where mobility is often a matter of survival rather than preference.

Case Study One South Sudan Migration

To test their model, the researchers examined migration patterns in South Sudan, a country where population movement is heavily influenced by instability. When conflicts were analyzed in isolation, traditional models struggled to explain observed migration flows.

However, when conflicts were considered together with natural hazards, particularly severe flooding, the predictions improved significantly. The combined effect of violence and environmental stress created strong push factors that traditional models failed to capture.

This finding highlights an important insight: migration drivers often interact, and their combined impact can be greater than the sum of their parts. A model that ignores these interactions risks oversimplifying complex human behavior.

Case Study Two United States Commuting Patterns

The researchers also applied their model to commuting data in the United States, a very different context from South Sudan but one that still reveals stark inequalities. In this case, the model included variables such as:

- The fraction of household income spent on rent

- The proportion of people living in severe poverty

- Measures of income inequality

When these factors were added, commuting patterns were predicted more accurately than with the standard radiation model alone. This suggests that even daily mobility decisions, like commuting to work, are shaped by economic stress and housing pressures, not just distance and job availability.

Better, Though Not Perfect, Predictions

The authors are clear that their model does not perfectly replicate real-world behavior. There remains a gap between predictions and observed movements. However, in both South Sudan and the United States, the inequality-aware model consistently outperformed the traditional radiation model.

This improvement is significant because it shows that incorporating social and economic realities makes mobility modeling more robust and useful, even if it cannot capture every nuance of human decision-making.

Why This Matters for the Future

As climate-related disasters become more frequent and socioeconomic inequalities deepen, migration is expected to increase worldwide. Forecasting these movements accurately is essential for:

- Urban planning

- Disaster preparedness

- Humanitarian response

- Infrastructure and housing policy

A model that is sensitive to quality-of-life differences between locations can help policymakers anticipate where people are likely to go and why. This, in turn, can guide better allocation of resources and more humane responses to displacement.

Understanding Push and Pull Factors in Human Mobility

In migration research, push factors are conditions that encourage people to leave an area, such as violence, poverty, or environmental danger. Pull factors are conditions that attract people to a destination, including safety, employment opportunities, and affordable living.

What makes this study stand out is that it treats push and pull not as abstract ideas, but as quantifiable variables that can be integrated into mathematical models. This bridges the gap between theoretical modeling and lived experience.

A Broader Shift in Mobility Science

The study challenges a long-standing assumption in mobility science: that places can be treated as interchangeable units differentiated only by size and distance. By showing that inequality matters, it pushes the field toward a more realistic understanding of human movement.

This approach aligns with broader trends in social science, where researchers increasingly recognize that context matters. People do not move in a vacuum. They respond to risk, opportunity, and inequality in ways that models must reflect if they are to remain relevant.

Final Thoughts

This research offers a clear message: if we want to understand and predict human mobility, we must look beyond maps and numbers and pay attention to how people actually live and work. By incorporating living conditions and job quality into mobility models, researchers are opening the door to more accurate forecasts and more informed decision-making in a rapidly changing world.

Research paper:

https://academic.oup.com/pnasnexus/article/5/1/pgaf407