Why Combining Clean Energy Incentives and Pollution Penalties Is Essential for Cutting Carbon Emissions Long Term

A new climate policy study offers a clear message that many researchers have hinted at for years but never demonstrated this thoroughly: clean energy incentives alone are not enough to stop climate change. According to a major new paper published in Nature Climate Change, the most effective way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions over the long term is by combining financial rewards for clean energy with penalties for pollution—and doing so in a consistent, well-timed way.

The study was conducted by a team of researchers from several leading institutions, including Princeton University and the University of California San Diego, and it arrives at a moment when climate policy in the United States and globally is facing deep uncertainty.

At its core, the research looks at a simple but powerful question: How should governments sequence climate policies over time to actually achieve deep decarbonization?

A Closer Look at the Study and Its Purpose

The research focuses on how real-world climate policies play out when modeled realistically, instead of relying on idealized assumptions. While many economic models assume governments will adopt a single, economy-wide carbon tax, this has rarely happened in practice—especially in the United States.

Instead, governments typically rely on a mix of policies. These include subsidies, tax credits, grants, and rebates to encourage clean energy adoption, alongside regulations or pricing mechanisms that make polluting activities more expensive. Until now, however, most climate models struggled to accurately represent this mixed-policy approach.

This study breaks new ground by showing how both incentives and penalties can be modeled together in a way that reflects how governments actually behave.

How the Researchers Modeled Climate Policy

To test different policy strategies, the research team used a sophisticated multisector energy model known as GCAM-U.S. This model simulates energy systems, technology costs, emissions, and investment decisions across all 50 U.S. states, projecting outcomes through the year 2050.

Importantly, the model incorporates real-world federal and state policies, rather than hypothetical or purely theoretical ones. This allows the researchers to explore realistic “what-if” scenarios involving policy adoption, delays, reversals, and sequencing.

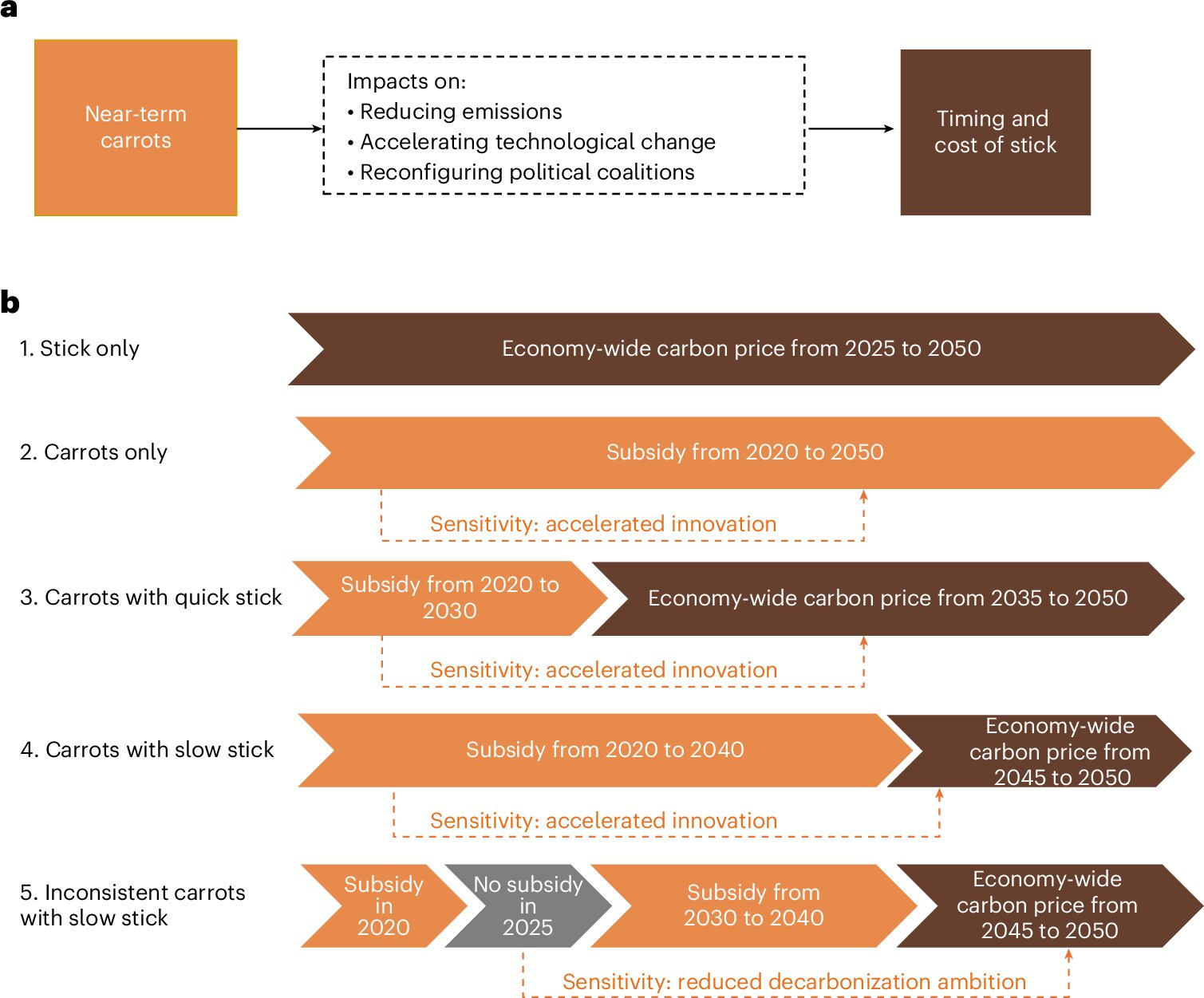

The researchers tested several distinct policy pathways, including:

- Incentives only, such as long-term subsidies for renewable energy and electric vehicles

- Penalties only, including economy-wide carbon pricing that raises the cost of fossil fuels

- Combined approaches, where incentives are introduced first and penalties follow after 10 or 20 years

- Inconsistent policies, reflecting political instability where incentives start, stop, and restart over time

By comparing these scenarios, the team was able to measure how each approach affects emissions reductions, clean technology adoption, and long-term costs.

What the Results Reveal About Incentives

One of the most striking findings is just how powerful incentives can be in the near term. Policies like electric vehicle tax credits, renewable energy subsidies, clean manufacturing grants, and home energy rebates significantly accelerate the adoption of clean technologies.

When incentives are strong and predictable, companies and consumers respond quickly. Renewable energy expands faster, electric vehicles become more common, and clean manufacturing scales up sooner than expected.

In fact, the researchers were surprised by how much progress incentives alone can generate in the early stages of the energy transition. These “carrot” policies lower costs, reduce risks, and help new technologies gain market share.

However, this success comes with an important limitation.

Why Penalties Are Still Necessary

Despite their early effectiveness, incentives on their own cannot deliver deep decarbonization. Over time, emissions reductions begin to stall unless there are policies that directly discourage pollution.

The study shows that without penalties—such as carbon pricing or pollution taxes—fossil fuels remain competitive in certain sectors, especially where alternatives are harder or more expensive to deploy. This makes it impossible to reach the deep emissions cuts needed to stabilize the climate.

In simpler terms, rewards can start the transition, but punishments are needed to finish it.

The most successful scenarios in the model were those where incentives were introduced first to build clean energy momentum, followed by penalties that steadily raised the cost of emitting carbon. This sequencing allows cleaner technologies to mature before facing stronger competition from polluting alternatives.

The Role of Political Timing and Consistency

Another major insight from the study is the importance of policy consistency. The researchers found that stable, long-term incentives are just as important as the size of those incentives.

When policies remain predictable, businesses invest with confidence. Clean energy projects move forward, supply chains expand, and costs fall over time. In these scenarios, the U.S. energy system can achieve around an 80% reduction in energy-related carbon emissions by mid-century.

By contrast, when incentives are withdrawn, delayed, or repeatedly changed, investment slows. Companies hesitate, projects are postponed, and emissions reductions become more expensive later on. Political uncertainty, the study shows, can seriously undermine long-term climate goals.

Why This Matters Right Now

The timing of this research is particularly significant. In the United States, many clean energy incentives introduced under the Inflation Reduction Act are now facing uncertainty due to political shifts in 2025. At the same time, the U.S. has never implemented a meaningful national tax on carbon emissions.

Globally, countries are taking very different approaches. China is expanding both incentives and penalties. Europe is relying heavily on emissions pricing. The result is a real-time global experiment in climate policy design.

Although the study focuses on the United States, the researchers emphasize that its findings are highly relevant for other countries trying to balance political feasibility with climate ambition.

Making Climate Models More Realistic

Beyond its policy conclusions, the study represents a broader effort to make climate modeling more realistic. Traditional models often prioritize economic efficiency over political reality, assuming governments will adopt policies that are unlikely to survive real-world politics.

This research aims to bridge that gap by showing how durable, politically realistic policy mixes can still achieve meaningful emissions reductions. By accounting for policy sequencing, reversals, and uncertainty, the model offers a more accurate guide for decision-makers.

Understanding Incentives and Penalties in Climate Policy

To put this in context, climate incentives typically include tools like tax credits, rebates, grants, and low-interest loans designed to lower the cost of clean technologies. Penalties, on the other hand, raise the cost of pollution through mechanisms such as carbon taxes, emissions trading systems, or regulatory fees.

Both tools influence behavior in different ways. Incentives encourage voluntary adoption, while penalties reshape markets by making polluting options less attractive. This study confirms that neither tool works best alone.

The Bigger Picture

The key takeaway from this research is straightforward: climate policy works best when rewards and consequences are used together, consistently, and with careful timing. Incentives can jump-start change, but penalties are essential to lock in long-term progress.

As governments around the world rethink their climate strategies, this study provides a clear, data-driven framework for designing policies that are not just economically sound, but politically durable.

Research Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-025-02497-6