Why Growing Up in a Violent U.S. State Can Increase Your Risk of Dying Violently Even After You Move Away

A new large-scale academic study is raising an uncomfortable but important question: does where you grow up shape your risk of violence for the rest of your life, no matter where you move? According to newly published research, the answer appears to be yes.

The study, conducted by political scientists at the University of California, Berkeley and Aarhus University in Denmark, finds that Americans who grow up in historically violent states carry a long-lasting elevated risk of dying violently, even if they later relocate to states that are considered much safer. This pattern holds across decades, social classes, age groups, and even across very different local environments.

At the center of the research is the idea that violence is not only about place, but also about learned behavior, expectations, and culture—factors that can follow people long after they leave home.

The Core Finding: Violence Risk Follows People Across State Lines

The study, titled Migration and the Persistence of Violence, analyzed millions of U.S. death records spanning more than half a century. The researchers examined whether people born in violent states continued to face higher risks of violent death after moving elsewhere.

What they found was striking. People born in historically high-homicide states were significantly more likely to die from violence later in life, regardless of whether they moved to safer states in the Northeast, Midwest, or other low-crime regions. Meanwhile, individuals born in historically safer states maintained a lower risk of violent death even after moving to more dangerous areas.

In other words, migration alone does not erase the effects of early exposure to violence.

Who Conducted the Study and Where It Was Published

The research was led by Gabriel Lenz, a political scientist at UC Berkeley who specializes in crime and criminal justice. His co-authors were Martin Vinæs Larsen, an associate professor at Aarhus University in Denmark, and Anna Mikkelborg, a UC Berkeley Ph.D. graduate who is now an assistant professor at Colorado State University.

The study was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) in December 2025, one of the most respected peer-reviewed scientific journals in the world.

How the Researchers Analyzed Violence Across Generations

To understand how violence persists, the researchers relied on a unique feature of U.S. death records. Starting in 1933, death certificates began recording the state of birth, state of death, cause of death, age, gender, and marital status of the deceased.

Using this information, the researchers first calculated homicide rates by state of birth during the 1930s, a period with stark regional differences in violence. They then tracked people born in those states who died decades later during three major periods: 1959–1961, 1979–1991, and 2000–2017.

This approach allowed them to compare people with similar demographic characteristics who lived in the same places—but who grew up in very different violence environments.

Which States Were Historically More Violent

The data shows that homicide rates have long been higher in certain parts of the United States, particularly the Deep South, Appalachian states, and parts of the Western frontier. States such as Kentucky, Louisiana, and Nevada consistently ranked among the most violent for white residents during the 1930s.

In contrast, states like Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and Wisconsin were among the safest during the same period. These historical differences turned out to be surprisingly powerful predictors of future risk.

For example, a person born in Kentucky who later moved to Chicago faced a much higher likelihood of violent death than a person born in Massachusetts who also moved to Chicago—even when controlling for income, education, age, and marital status.

The Risk Extends Across Demographics

One of the most important aspects of the study is how broad and persistent the effect is. The elevated risk was not limited to young men, who are typically most associated with violent crime statistics.

The pattern held true for:

- Married women

- People over the age of 75

- Individuals with higher education

- People with higher incomes

Even groups that are normally considered low-risk showed increased vulnerability if they were born in historically violent states. This suggests that the mechanism behind the risk goes beyond immediate social conditions.

Violence From Both Interpersonal Conflict and Police Encounters

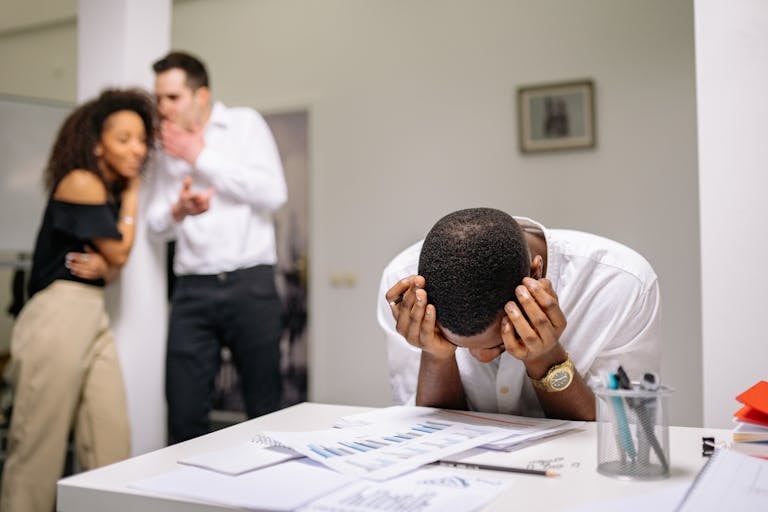

The study also found that the elevated risk includes both interpersonal violence and deaths involving law enforcement. Migrants from violent states were more likely to die during conflicts with other individuals and during encounters with police, even when living in states with lower overall crime rates.

This finding adds another layer to ongoing discussions about policing, public trust, and how people respond to authority in high-stress situations.

The Role of America’s “Culture of Honor”

To better understand why this pattern exists, the researchers conducted a large survey of nearly 7,500 migrants and non-migrants. The survey measured attitudes toward danger, aggression, self-reliance, and law enforcement.

People from historically violent states—whether they had moved or not—were more likely to:

- View the world as a dangerous place

- React aggressively to perceived threats

- Value toughness and self-defense

- Distrust law enforcement

- Rely on family rather than institutions for protection

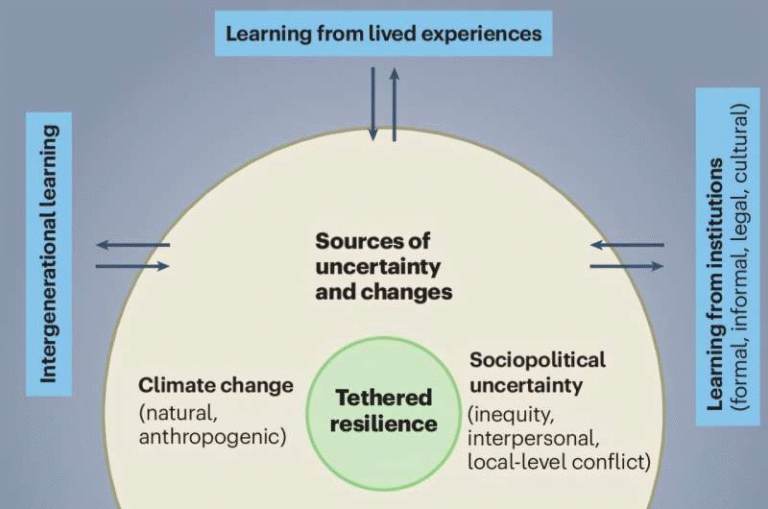

These attitudes are often associated with what scholars call a culture of honor, a social system that developed in places where formal government protection was weak and personal reputation mattered for survival.

While these behaviors may have helped people stay safe in dangerous environments, the study suggests they can increase the risk of fatal escalation in places where violence is less common.

Why Early Experiences Matter So Much

One of the broader insights from this research is how deeply early social environments shape lifelong behavior. Growing up in a violent setting appears to influence how people interpret threats, respond to conflict, and decide when to back down—or not.

Once violence begins, the researchers note, outcomes are unpredictable. In many cases, perpetrators and victims overlap, and escalation happens quickly. The result is that people who expect violence may unintentionally place themselves in situations where the risk of death is higher.

Important Limitations of the Study

Due to historical data constraints, the high-precision analysis focused primarily on white, non-Hispanic Americans. In the 1930s, Black Americans were overwhelmingly born in a small number of Southern states, most of which had very high homicide rates. This made it statistically impossible to create a low-risk comparison group for Black migrants.

The researchers believe the same mechanisms likely apply to Black Americans, but they emphasize that the study could not directly test this due to data limitations. Similar challenges prevented a detailed analysis of Hispanic and immigrant communities.

What This Research Suggests About Public Policy

The study raises important questions about long-term violence prevention. If cultural expectations and distrust in institutions drive risk, then improving public safety alone may not be enough.

The authors suggest that consistent, trustworthy law enforcement and effective public institutions could help reduce the belief that individuals must rely on force to protect themselves. Over time, this could weaken the cycle that allows violence to persist across generations and regions.

Why This Study Matters

This research challenges the idea that moving to a safer place automatically leads to safer outcomes. It shows that violence can be socially transmitted, shaped by history, and carried within people rather than places.

Understanding this dynamic may help explain why homicide rates remain stubbornly persistent in certain populations—and why solutions need to address both environmental safety and deeply ingrained cultural expectations.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2500535122