A Black Hole Devouring a Star Created the Longest Gamma-Ray Burst Ever Recorded

Astronomers have documented one of the most extreme cosmic explosions ever observed: a gamma-ray burst that lasted for days instead of seconds, challenging decades of assumptions about how these events occur. The outburst, known as GRB 250702B, was detected in July 2025 and is now believed to be linked to a black hole consuming a star in a way never clearly observed before. The discovery was made by an international team of scientists, including George Washington University physics Ph.D. student Eliza Neights, working closely with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Gamma-ray bursts, or GRBs, are already known as the most powerful explosions in the universe, typically releasing enormous amounts of energy in a matter of seconds or minutes. What makes GRB 250702B extraordinary is its unprecedented duration. While most GRBs fade quickly, this one remained active for at least seven hours in gamma rays, with follow-up emissions continuing for days. In fact, it lasted about 420 times longer than a typical stellar-collapse GRB, making it the longest such event recorded since GRBs were first identified in the early 1970s.

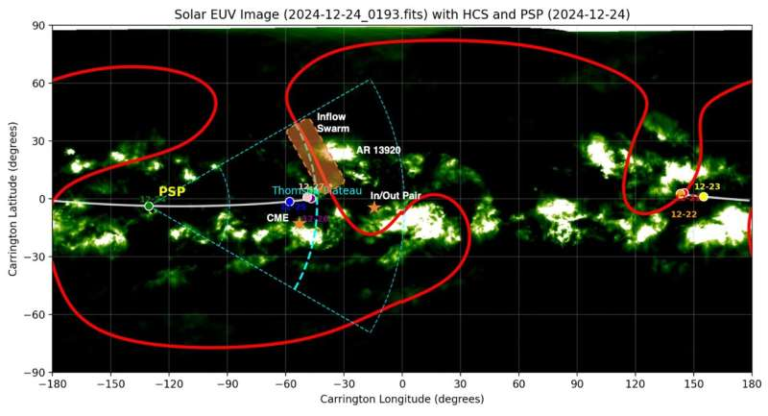

GRB 250702B was first detected by the Gamma-ray Burst Monitor aboard NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, which triggered repeatedly over a three-hour span. Additional detections came from an impressive fleet of space-based instruments, including NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, the Konus instrument on the Wind spacecraft, the Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometer aboard NASA’s Psyche mission, and Japan’s MAXI instrument on the International Space Station. No single observatory was equipped to monitor such a long-lasting event on its own, making this a rare case where multi-mission collaboration was essential.

Adding to the mystery, China’s Einstein Probe detected X-rays from the same region a full day before the gamma-ray burst was officially discovered, while NASA’s NuSTAR and Swift telescopes observed intense X-ray flares up to two days after the main burst. This behavior is highly unusual for standard GRBs, which typically show a rapid rise and fall without such extended activity.

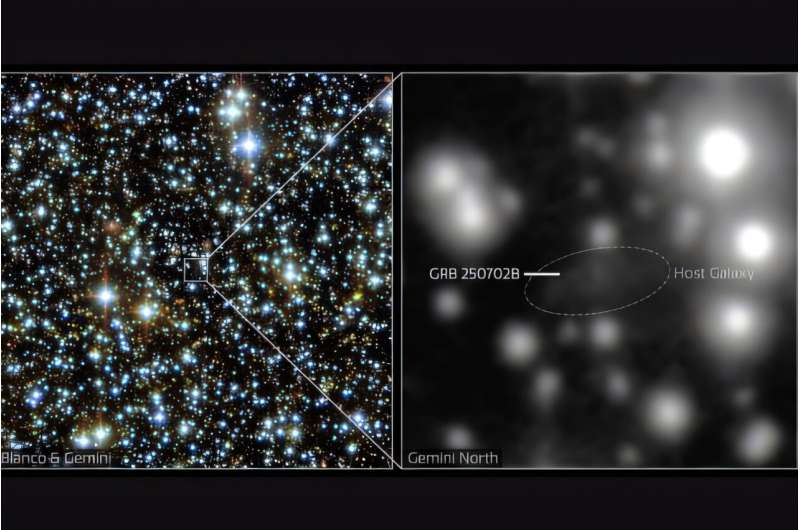

The first precise location of GRB 250702B was pinned down on July 3, when Swift’s X-Ray Telescope imaged the burst in the constellation Scutum, close to the dense and dusty plane of the Milky Way. Because of this crowded region and the early X-ray detection, astronomers initially questioned whether the event might be coming from within our own galaxy. However, observations from major ground-based telescopes—including Keck and Gemini in Hawaii and the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile—hinted at the presence of a distant galaxy at the source location.

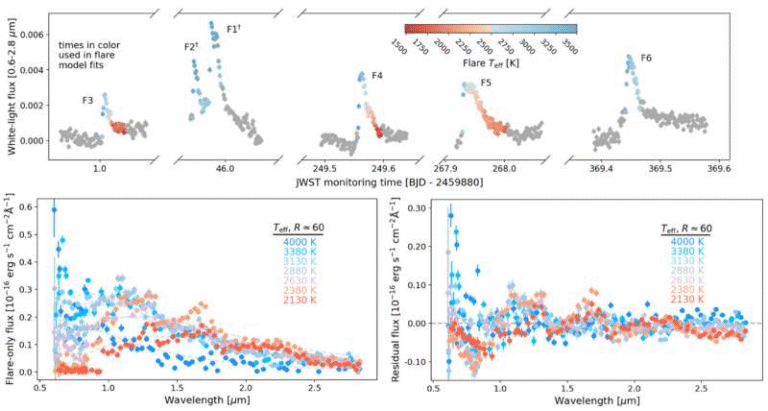

That suspicion was confirmed by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, which revealed a strange-looking host galaxy. The images suggested either two galaxies in the process of merging or a single galaxy split by a thick lane of dust. Later observations from the James Webb Space Telescope’s NIRCam instrument provided stunning clarity, showing that the burst’s light passed directly through a dense dust lane within the galaxy. The galaxy is so distant that its light has taken about 8 billion years to reach Earth, meaning the explosion occurred long before our Sun and solar system formed.

Further analysis using Webb and the VLT, led by researchers at the University of Birmingham, showed just how extreme the explosion was. The burst released energy equivalent to a thousand Suns shining continuously for 10 billion years. This places GRB 250702B among the most energetic events ever measured.

What truly sets this event apart, however, is that it doesn’t fit neatly into existing GRB models. Most long-duration GRBs are associated with the collapse of massive stars, usually followed by a visible supernova explosion. Yet spectroscopic observations from Webb did not clearly detect a supernova, although researchers caution that dust and distance may have hidden it from view. Additionally, the host galaxy itself is unusual. Unlike the small, low-mass galaxies that typically host stellar-collapse GRBs, this galaxy appears to be massive—more than twice the mass of the Milky Way.

To explain all of these anomalies, scientists are considering two main scenarios, both involving a black hole consuming a star.

The first possibility involves a rare intermediate-mass black hole, weighing a few thousand times the mass of the Sun. In this scenario, a star strays too close and is torn apart by intense gravitational forces in what is known as a tidal disruption event. As the shredded star spirals inward, it forms a massive accretion disk that feeds the black hole and powers long-lived jets of gamma rays.

The second scenario, which many members of the gamma-ray team currently favor, involves a stellar-mass black hole, roughly three times the mass of the Sun, orbiting a companion helium star. This companion would be a stripped-down stellar core, having lost most of its hydrogen envelope. As the black hole merges with and plunges into the helium star, it feeds continuously from within, keeping the energy output alive for days. This model predicts that the black hole eventually becomes fully embedded inside the star, triggering a supernova explosion from the inside out. Unfortunately, if such a supernova occurred here, it would have been hidden behind enormous amounts of cosmic dust.

In both scenarios, matter first accumulates in a vast disk around the black hole before plunging inward. At a critical point, the system begins shining brightly in X-rays, followed by the launch of powerful gamma-ray jets moving at nearly the speed of light. The extended feeding process explains why the energy source behind GRB 250702B refused to shut off, unlike anything seen before.

Beyond its immediate mystery, GRB 250702B offers a rare opportunity to learn more about how black holes grow, how stars die, and how extreme physics operates under conditions that cannot be replicated on Earth. Ultra-long GRBs like this one allow astronomers to collect richer datasets over extended periods, providing deeper insight into accretion disks, relativistic jets, and the behavior of matter near an event horizon.

While definitive proof of exactly which scenario occurred will require future observations of similar events, GRB 250702B has already reshaped how scientists think about the upper limits of gamma-ray burst duration. Thanks to constant all-sky monitoring by modern space observatories, astronomers are now better equipped than ever to catch these rare cosmic catastrophes in action.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staf2019