A Century’s Worth of Solar Data Could Help Predict Future Solar Cycle Activity

Scientists are getting closer to understanding one of the Sun’s most stubborn mysteries: how its activity rises and falls over time, and how we might predict what it will do next. A new international study suggests that the key may lie in more than 100 years of historic solar observations, carefully reanalyzed with modern techniques.

An international team of astronomers from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in the United States, the Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences (ARIES) in India, and the Max Planck Institute in Germany has shown that century-old data can be used to reconstruct the Sun’s polar magnetic field. This reconstruction could significantly improve long-term predictions of future solar cycles and help scientists better prepare for space weather events that affect Earth and space-based technology.

Why Solar Cycles Matter More Than You Might Think

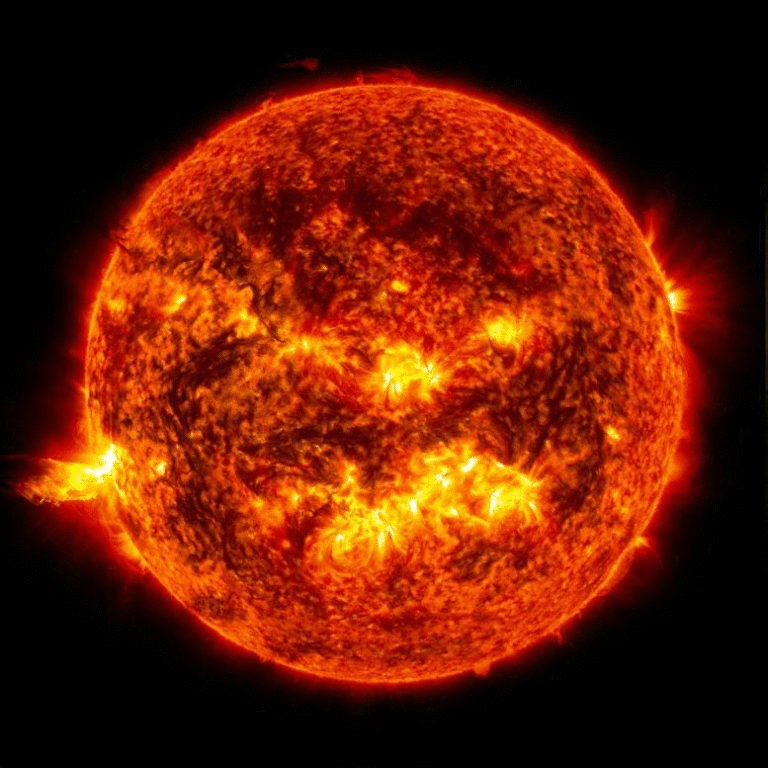

The Sun follows a roughly 11-year cycle of activity marked by changes in sunspots, solar flares, coronal mass ejections, and magnetic storms. During periods of high activity, the Sun can eject massive bursts of charged particles and radiation into space.

These events don’t just look dramatic—they can interfere with satellites, GPS systems, radio communications, power grids, and space missions. Understanding and predicting solar activity is therefore critical for protecting modern technological infrastructure.

One of the most important indicators of future solar activity is the Sun’s polar magnetic field. Scientists have learned that the strength of this polar field near the minimum of one solar cycle is closely linked to how strong the next cycle will be. The problem is that direct measurements of the Sun’s polar magnetic field only began in the 1970s, leaving a huge gap in historical data.

Looking Back to Look Ahead

To overcome this limitation, the research team turned to a remarkable archive from the Kodaikanal Solar Observatory (KoSO) in India. Solar astronomers at KoSO have been observing the Sun in Calcium-II K (Ca II K) light since 1904, creating one of the longest continuous records of solar observations in the world.

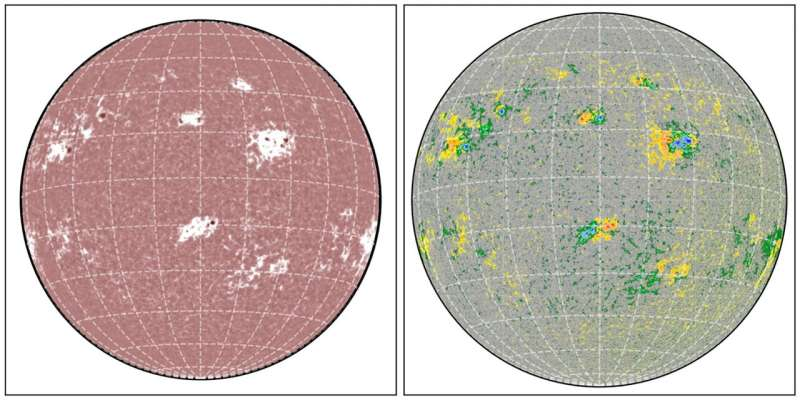

Ca II K observations capture the Sun’s chromosphere, a layer just above the visible surface. In this layer, magnetic activity shows up as bright patches and networks, which can act as indirect indicators—or proxies—of magnetic fields.

The challenge was that these historic images were never intended to be used for precise magnetic measurements. Over the decades, inconsistencies crept in, including time-zone errors, rotation mismatches, and calibration issues.

Cleaning and Calibrating a Century of Solar Images

A crucial part of the study involved correcting and standardizing the historic KoSO data so it could be reliably compared with modern measurements. A scientist from SwRI focused on identifying and fixing anomalies in the old data, aligning the historic images with today’s reference standards.

Once the data were corrected, the team compared the Ca II K images with direct magnetic field measurements from the Michelson Doppler Imager aboard the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO). This comparison revealed a strong correlation between bright Ca II K regions and magnetic activity, particularly near the Sun’s poles.

This correlation confirmed that Ca II K observations could indeed be used to reconstruct the Sun’s polar magnetic behavior long before direct measurements were available.

Automating the Analysis of 50,000 Solar Images

One of the biggest hurdles was scale. The KoSO archive contains around 50,000 solar images, far too many to analyze manually.

To solve this, the lead author of the study developed an automated algorithm that scans the corrected images and identifies the bright chromospheric features associated with magnetic activity near the poles. From this, the team derived a metric known as the Polar Network Index (PNI).

The PNI acts as a proxy for the Sun’s historical polar magnetic field, allowing researchers to track its evolution across more than a century of solar cycles.

Extending the Solar Magnetic Record by Decades

Using this method, the team successfully reconstructed polar magnetic field behavior across multiple solar cycles, reaching back to the early 20th century. This dramatically extends the available dataset beyond what was previously possible using direct measurements alone.

The reconstructed polar field data shows strong consistency with modern observations and aligns well with known patterns in solar cycle strength. This validation suggests that the PNI is a reliable and scientifically robust tool for studying long-term solar magnetic behavior.

Why the Sun’s Poles Are So Hard to Study

One interesting challenge highlighted by the research is that Earth’s tilted orbit limits how often we get a clear view of the Sun’s poles. Even with modern instruments, astronomers can only observe the poles clearly a few times each year.

This makes historical data even more valuable. By analyzing the Sun’s chromosphere over long periods, scientists can fill in observational gaps and gain insights that would otherwise be impossible.

Implications for Predicting Future Solar Cycles

At present, scientists can reliably predict solar activity only about five years in advance. This is not ideal for long-term planning, especially for space agencies like NASA, which must design missions decades before launch.

By extending the polar magnetic field record back more than 100 years, this research offers a way to improve statistical models of solar cycles and potentially enhance long-range forecasting.

However, the researchers caution that predictions still need to be tested against future observations. It will take another four to five years before scientists can confirm how accurately the reconstructed data predicts the behavior of Solar Cycle 26.

The Case for Future Solar Polar Missions

The study also strengthens the argument for a dedicated solar polar mission. Most current spacecraft observe the Sun from near the plane of the solar system, known as the ecliptic. A mission designed to observe the Sun from higher latitudes could directly monitor polar magnetic fields over time.

Until such missions become a reality, historic datasets like those from KoSO remain one of the best tools available for understanding long-term solar magnetic processes.

A Broader Perspective on Solar Research

This work highlights the growing importance of data preservation and reanalysis in modern science. Observations made more than a century ago, using techniques far less advanced than today’s, are now proving essential for answering some of the most pressing questions in heliophysics.

It also underscores how international collaboration—combining expertise in solar physics, data processing, and instrumentation—can unlock new insights from old records.

What This Means Going Forward

By uncovering hidden magnetic information in historic solar observations, scientists have taken a meaningful step toward better space weather forecasting. Improved predictions could help safeguard satellites, astronauts, power grids, and future space missions.

More broadly, this research reminds us that understanding the Sun is not just an academic pursuit. It directly affects how we live, communicate, and explore space.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/adb3a8