ALMA Devours a Cosmic Hamburger and Reveals New Clues About Giant Planet Formation

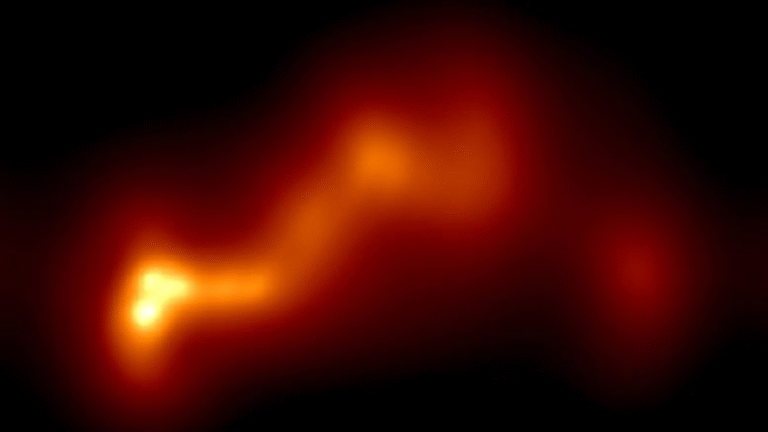

Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) have taken an unusually detailed look at one of the most visually striking and scientifically intriguing protoplanetary disks known today: Gomez’s Hamburger, often shortened to GoHam. What they found goes far beyond a catchy nickname. The observations provide rare, direct evidence of the earliest stages of giant planet formation, happening inside a massive, layered disk of gas and dust surrounding a young star.

Gomez’s Hamburger gets its playful name from its appearance. Seen almost perfectly edge-on, the system looks like a cosmic sandwich, with dark and bright layers stacked above and below a dense midplane. While the nickname has been around for years, ALMA’s latest observations have finally allowed astronomers to truly “take a bite” out of the system and understand what those layers are made of and how they behave.

A Rare Edge-On View Into a Planet-Forming Disk

Most protoplanetary disks are observed at tilted angles, which makes it difficult to separate what is happening vertically within the disk. GoHam is different. Its nearly edge-on orientation gives astronomers a direct view of its vertical structure, offering insights that are usually hidden in other systems.

Using ALMA’s sensitivity at millimeter wavelengths, researchers were able to map both millimeter-sized dust grains and several types of gas-phase molecules. These observations clearly show that the disk is not a uniform cloud but a highly organized structure with distinct layers that change with height above the midplane.

A Stacked Structure of Gas and Dust

One of the most important results from the ALMA data is how cleanly the disk’s vertical stratification can be seen. Different gases occupy different heights, exactly as theoretical models predict, but rarely observe so clearly.

The lightest gas detected, carbon monoxide made of the common isotope 12CO, sits highest above and below the disk’s midplane. Slightly closer in is 13CO, a heavier version of carbon monoxide. Even closer to the midplane lies carbon monosulfide (CS), along with sulfur monoxide (SO) in more localized regions. This layered arrangement reflects how temperature, density, and chemistry change with height inside the disk.

In contrast, the millimeter-sized dust grains form a relatively thin and dense layer right along the midplane. This sharp separation between gas and dust highlights just how “puffed up” the gaseous component of the disk is compared to the solid material. For planet formation, this distinction matters, because dust grains are the building blocks that eventually clump together to form planets.

One of the Largest Planet-Forming Disks Known

Size is another reason Gomez’s Hamburger stands out. The disk is truly enormous. Observations show that 12CO gas extends to nearly 1,000 astronomical units (AU) from the central star, and the disk reaches vertical heights of several hundred AU. This places GoHam among the largest known planet-forming disks ever observed.

The disk is not just large but also massive. The total dust mass is estimated to be many times higher than what is typically seen around similar young stars. This abundance of material dramatically increases the system’s potential to form giant planets and possibly even a multi-planet system in the future.

A Disk With Asymmetry and Disturbances

Despite its orderly layered structure, GoHam is far from perfectly symmetrical. ALMA observations reveal that the millimeter dust emission is lopsided in the north–south direction. One side of the disk appears brighter and more extended than the other.

This asymmetry is thought to be caused by a vortex or large-scale disturbance within the disk. Such features are especially interesting because they can act as dust traps, collecting solid material in one region and making it easier for planets to form. Instead of dust grains drifting inward toward the star, the vortex can hold them in place long enough for them to grow.

Signs of Gas Being Blown Away

Another striking feature is the presence of faint, extended carbon monoxide emission in the northern part of the disk, especially at large distances from the star. This emission is consistent with a photoevaporative wind, a process in which energetic starlight slowly heats and pushes gas away from the disk.

Photoevaporation plays a key role in disk evolution. Over time, it can remove large amounts of gas, influencing how long planet formation can continue and shaping the final architecture of the planetary system.

A Possible Planet in the Making: GoHam b

Perhaps the most exciting result from the ALMA observations is the detection of a one-sided arc of sulfur monoxide (SO) emission just outside the brightest dust region on one side of the disk. This SO arc follows the disk’s rotation, indicating that it is part of the system rather than an unrelated feature.

Crucially, the arc lines up with a previously identified dense clump known as GoHam b. This clump is thought to be material collapsing under its own gravity, potentially representing one of the earliest observable stages of a massive planet forming at a wide orbit.

If confirmed, GoHam b would be an important example of giant planet formation far from a star, a scenario that challenges traditional models which often focus on planet formation closer in.

Why Gomez’s Hamburger Matters

GoHam offers astronomers something rare: a benchmark system where disk structure, chemistry, dynamics, and potential planet formation can all be studied together in exceptional detail. Its extreme size, strong asymmetries, active gas winds, and possible forming planet make it a natural laboratory for testing and refining models of how disks evolve.

Understanding systems like GoHam helps answer broader questions about how common giant planets are, how they form at large distances, and how their presence reshapes the surrounding gas and dust.

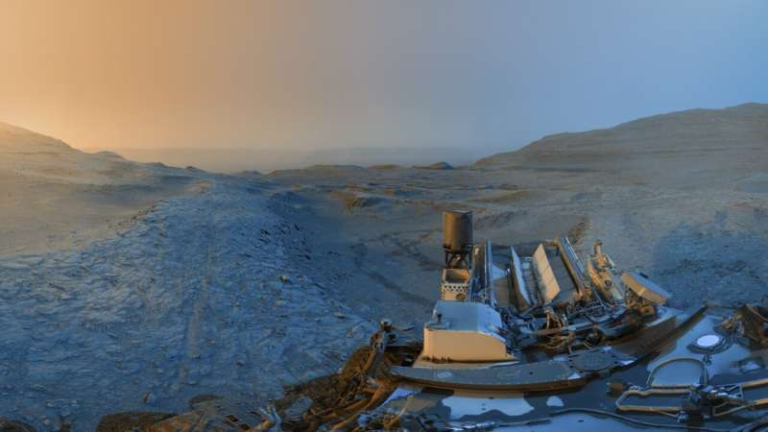

Extra Context: How ALMA Sees the Invisible

ALMA’s power comes from its ability to observe cold gas and dust that emit weakly at millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths. These wavelengths are ideal for studying protoplanetary disks, where temperatures are often just tens of degrees above absolute zero.

By observing specific molecules like CO, CS, and SO, astronomers can trace temperature, density, motion, and chemistry within disks. Combined with dust observations, this allows researchers to build a three-dimensional picture of systems like Gomez’s Hamburger.

Looking Ahead

The research on GoHam is still being prepared for formal publication, but even at this stage, the results are reshaping how astronomers think about giant planet formation. As ALMA continues to observe similar systems, Gomez’s Hamburger will likely remain a key reference point for years to come.

For now, this cosmic hamburger serves as a reminder that some of the most important discoveries come from looking at familiar processes, like planet formation, from a completely new angle.

Research reference:

https://www.almaobservatory.org/en/press-releases/a-cosmic-hamburger-offers-new-clues-to-giant-planet-formation/