Andromeda Galaxy Quenches Many of Its Satellite Galaxies Long Before They Even Fall In

Astronomers have long known that large galaxies grow by swallowing smaller ones, but new research on the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) paints a surprisingly complex picture of how its satellite dwarf galaxies stop forming stars. A new study examining 39 of M31’s known satellite galaxies reveals that many of them were quenched—meaning they lost the gas needed to form new stars—well before they ever reached Andromeda itself. This finding challenges the idea that big galaxies only quench satellites after they fall into their halos, and instead shows that many dwarfs arrive at the host galaxy already “dead.”

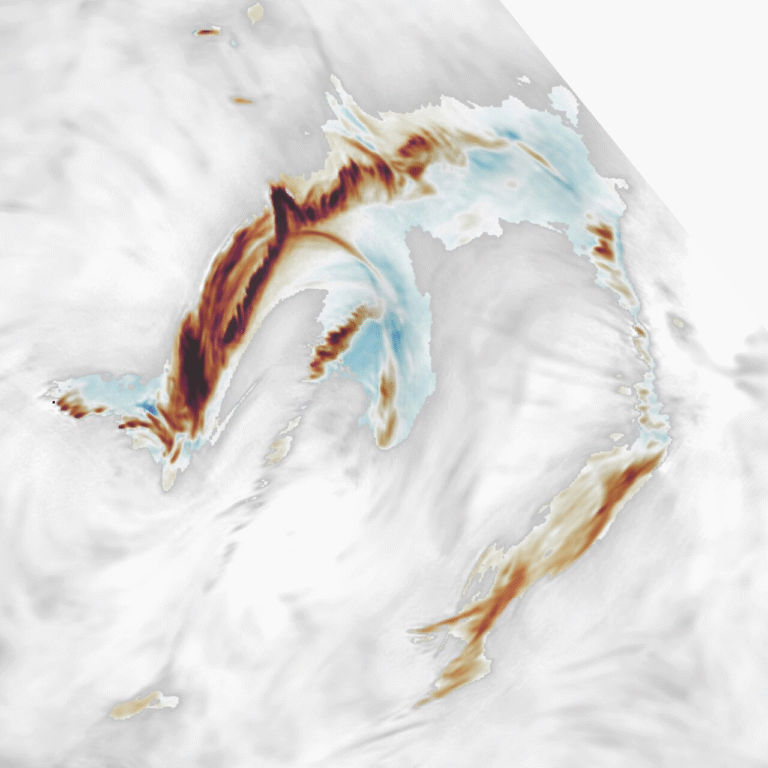

This work comes from a 2025 research paper titled The Lives and Deaths of Faint Satellite Galaxies Around M31, led by Alex Merrow of Durham University. The team combined cosmological N-body simulations with observed properties of Andromeda and its satellite system to estimate each dwarf galaxy’s proper motion, orbital history, infall time, and first pericenter passage—the point at which a satellite comes closest to its host. They then compared these orbital estimates with published star-formation histories of every satellite, allowing them to determine when star formation shut down relative to when a galaxy fell into Andromeda.

Most Of Andromeda’s Satellite Galaxies Stopped Forming Stars Before Infall

A key takeaway is that many of M31’s satellites quenched long before they got anywhere near Andromeda’s gravitational influence. The study shows:

- Only the most massive satellites (stellar masses above 10⁷.⁵ solar masses) could continue star formation for more than 3 billion years after their first pericenter.

- Lower-mass satellites, which make up the majority, were typically quenched well before their first close passage around Andromeda.

- Some of the least massive galaxies appear to have quenched as early as 10 billion years before reaching M31.

This means many satellites were already unable to form stars by the time they entered the Andromeda system. Instead of M31 actively stripping their gas, these dwarfs were shaped by earlier environments or cosmic processes.

Multiple Mechanisms Likely Shut Down Star Formation Early

The study identifies several reasons why these galaxies lost their ability to form stars long before falling into Andromeda.

1. Pre-Processing Near Smaller Host Galaxies

A major quenching pathway is pre-processing—when a dwarf galaxy orbits or interacts with a smaller intermediate host before ultimately reaching a large galaxy like M31.

During this phase, the dwarf experiences gravitational interactions or gas stripping that can heat, remove, or disturb its gas. When it finally approaches Andromeda, it is already gas-poor and unable to form stars.

Pre-processing appears to be a major factor for many of the faintest dwarfs.

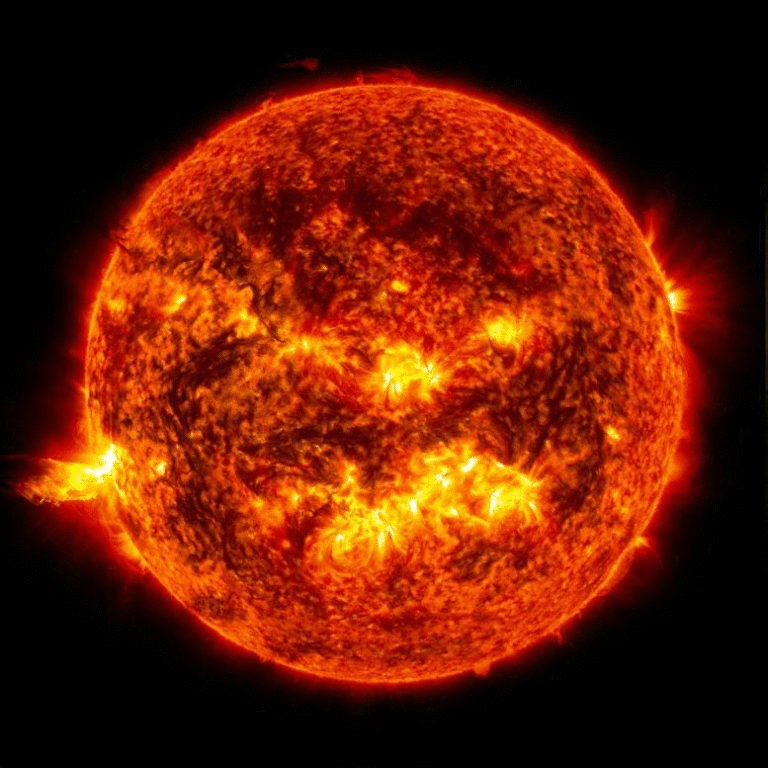

2. Reionization Heating the Gas in the Early Universe

Some dwarfs quenched extremely early, long before they could encounter any host galaxy.

This likely happened due to cosmic reionization, a period when strong ultraviolet radiation heated hydrogen gas across the Universe.

Low-mass dwarfs don’t have the gravitational strength to keep this gas bound, so it escaped into space.

This photo-evaporation left these galaxies permanently quenched over 12 billion years ago, making them fossils of the early Universe.

3. Environmental Effects From Andromeda (For More Massive Satellites)

For satellites that quenched after falling in, several environmental effects from Andromeda played a role:

- Ram-pressure stripping, where gas is pushed out as the dwarf moves through M31’s halo.

- Tidal stripping, where gravitational forces remove material.

- Shutoff of fresh gas accretion, preventing the satellite from replenishing star-forming material.

These mechanisms primarily affect galaxies with enough mass to survive until infall.

Andromeda and the Milky Way Have Very Different Satellite Populations

The researchers also compared their findings with what is known about the Milky Way’s satellite galaxies.

Interestingly, the two giant galaxies host qualitatively different histories among their dwarfs.

- Most of the Milky Way’s satellites show very old quenching times, typically older than 11 billion years.

- They also tend to have early infall times, over 9 billion years ago, with 76% of MW satellites falling into this category.

- By contrast, Andromeda’s satellites show a much wider spread in both infall and quenching times.

- This could mean the Milky Way cannibalized its satellites earlier, or it might reflect differences in how astronomers observe each system.

One high-profile exception in the Milky Way is the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, which are still forming stars because they are only now being pulled in.

The contrast implies that galaxy evolution may not follow the same pattern everywhere. Each large galaxy has its own unique environmental history and timing of mergers.

Why These Findings Matter

Understanding how and when a dwarf galaxy stops forming stars is crucial for building accurate models of galaxy formation and evolution.

Dwarf galaxies are the most common type of galaxy in the Universe, and satellites show how large galaxies grow over time.

This study suggests that:

- Environmental quenching by large hosts is only part of the story.

- Early-Universe physics and smaller host galaxies play major roles.

- Orbital histories are essential for interpreting why some dwarfs are star-forming while others are not.

In other words, galaxy evolution is not a simple “big galaxy kills small galaxy” sequence. There are multiple stages and multiple environments involved.

A Quick Overview of the Mechanisms Mentioned in the Study

Since readers may benefit from understanding some of the physical processes involved in quenching, here’s a straightforward rundown.

Ram-Pressure Stripping

This happens when a galaxy flies through the hot gas of a larger halo. The pressure pushes out the galaxy’s own gas.

Dwarfs with shallow gravitational wells lose gas quickly.

Tidal Stripping

The gravity of the big galaxy pulls stars and gas away from the smaller galaxy.

This can physically distort the dwarf or even tear it apart.

Cessation of Gas Accretion

If a galaxy can’t pull in new cold gas, star formation slowly shuts down as existing gas gets used up or heated.

Pre-Processing

A dwarf interacts with another halo long before reaching the main host.

This step can include gas loss, heating, or minor mergers.

Reionization Quenching

UV radiation in the early Universe heats gas in tiny galaxies until it escapes.

These dwarfs can remain quenched forever.

Understanding these processes also helps astronomers predict what the satellite systems of distant galaxies may look like.

What This Means for Future Research

The study highlights how improving proper motion measurements, simulations, and star-formation reconstructions is revealing much more nuanced life histories for small galaxies.

Andromeda, with its 39 known satellites, serves as an excellent laboratory for testing theories of galaxy evolution.

Future work will likely:

- Incorporate better proper-motion data as new observations come in.

- Compare satellite systems of more galaxies beyond the Local Group.

- Look more closely at the role of early pre-processing environments.

- Refine models of reionization-era quenching.

Each new insight helps astronomers better understand what galaxies looked like billions of years ago.

Research Paper:

The lives and deaths of faint satellite galaxies around M31

https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.01977