Astronomers Capture a Rare Image of a Real-Life Tatooine-Like Planet Orbiting Two Suns

Astronomers have achieved something truly remarkable: they have directly imaged a rare exoplanet orbiting two stars, a setup famously associated with the fictional planet Tatooine from Star Wars. While thousands of exoplanets have been discovered so far, very few have been directly photographed, and even fewer exist in binary star systems. This newly confirmed world stands out even more because it is the closest directly imaged circumbinary planet to its host stars ever found.

The discovery was led by researchers from Northwestern University, with independent confirmation by a European team from the University of Exeter. The findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and Astronomy & Astrophysics, marking an important milestone in the study of planet formation in complex star systems.

A Planet Orbiting Two Suns, Closer Than Ever Seen Before

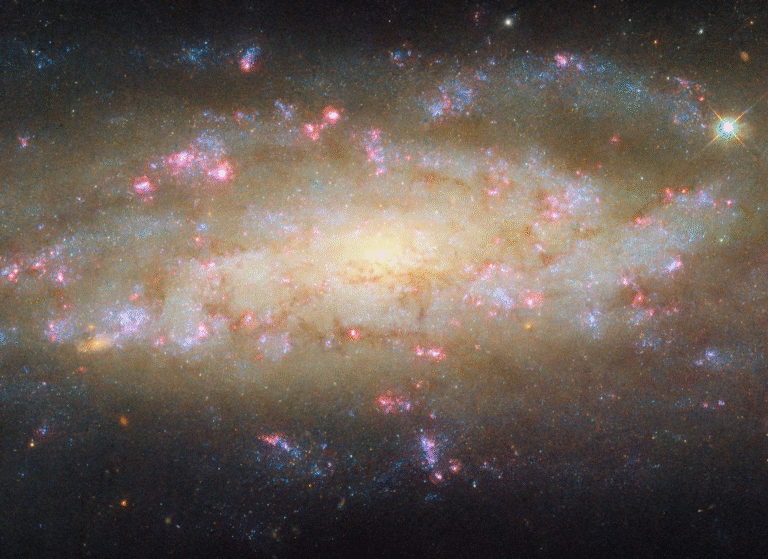

The newly imaged planet, named HD 143811 AB b, orbits a tightly bound pair of stars located about 446 light-years away from Earth. These two stars revolve around each other extremely quickly, completing one orbit in just 18 Earth days. By contrast, the planet follows a much wider and slower path, taking roughly 300 Earth years to complete a single orbit around both stars.

What makes this system exceptional is how close the planet is to its twin stars compared to other directly imaged circumbinary planets. In fact, it is about six times closer than any previously known example captured through direct imaging. This challenges existing assumptions about where planets can safely form and survive in binary systems, where gravitational forces are far more complex than around single stars like our Sun.

Why Direct Imaging Is Such a Big Deal

Most exoplanets are discovered using indirect methods, such as detecting tiny dips in starlight when a planet passes in front of its star or measuring subtle stellar wobbles caused by a planet’s gravity. Direct imaging, however, involves actually capturing light from the planet itself, which is extraordinarily difficult. Stars are incredibly bright, and their glare often overwhelms the faint glow of orbiting planets.

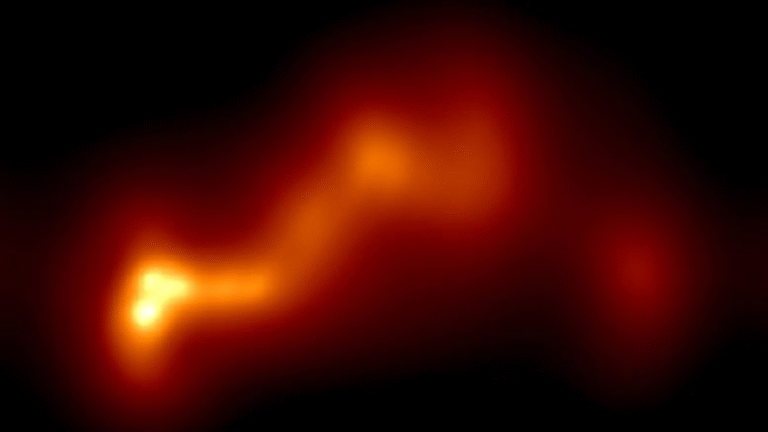

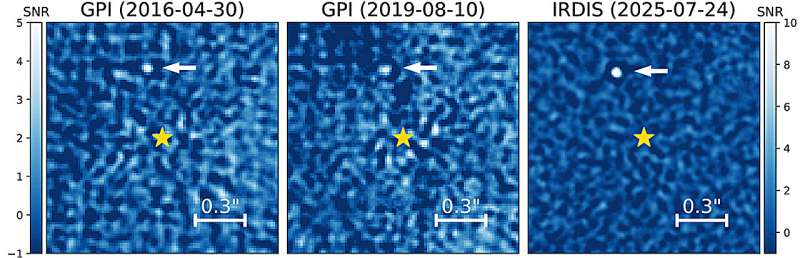

To overcome this challenge, astronomers relied on the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI), a specialized instrument designed to block out starlight using a coronagraph while employing adaptive optics to sharpen the image. GPI was originally installed at the Gemini South telescope in Chile, where it observed more than 500 stars during its operational lifetime.

Despite that massive survey, only one new planet was discovered at the time, highlighting just how rare directly imaged exoplanets truly are.

A Discovery Hidden in Plain Sight for Years

The story of this planet’s discovery did not begin with new observations but with a careful reanalysis of archival data. The GPI observations were taken between 2016 and 2019, and at the time, this planet went unnoticed.

Years later, as GPI was being upgraded for relocation to the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii, researchers decided to take one final, thorough look at the old data. During this reanalysis, a faint object repeatedly appeared to move in sync with the binary star system.

This was a critical clue. Objects that merely appear near stars often turn out to be unrelated background stars drifting across the field of view. A genuine planet, however, will move through space along with its host stars. Further analysis of the object’s light also showed that its spectral signature matched what astronomers expect from a planet rather than a star.

Around the same time, a European research team independently reexamined the same dataset and reached the same conclusion, providing strong confirmation that the object was indeed a planet.

A Massive and Surprisingly Young World

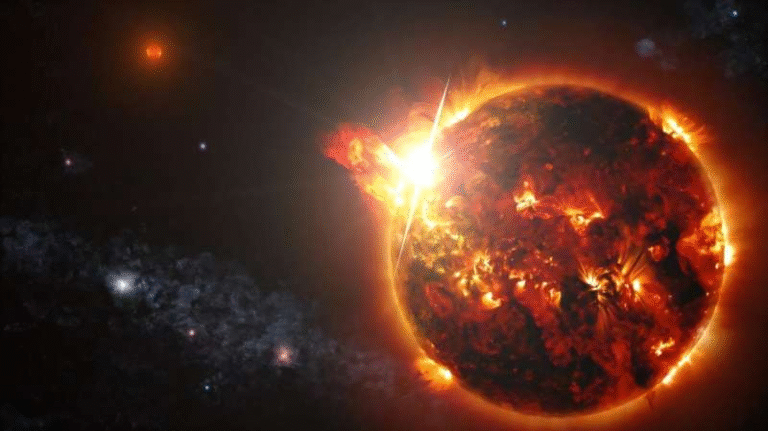

HD 143811 AB b is no small planet. It is a gas giant roughly six times the mass of Jupiter, making it one of the more massive directly imaged exoplanets known. Although it is hotter than any planet in our solar system, it is relatively cool compared to many other directly imaged exoplanets, which are often detected while still extremely hot from their formation.

The planet is estimated to be around 13 million years old, which is extraordinarily young in cosmic terms. To put that in perspective, this planet formed roughly 50 million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs. Because of its youth, it still retains significant heat from its formation, making it visible to infrared instruments like GPI.

Why Binary Star Planets Matter So Much

Out of the approximately 6,000 known exoplanets, only a small fraction orbit binary star systems. Even fewer have been directly imaged. Systems like HD 143811 are therefore incredibly valuable to astronomers because they allow scientists to observe both the stars and the planet moving across the sky simultaneously.

This makes it possible to precisely track orbital dynamics and test theories of planet formation under conditions very different from those in our solar system. One leading idea is that the binary stars formed first, followed by the planet forming from a surrounding disk of gas and dust. However, exactly how such disks remain stable long enough to form planets remains an open question.

The extreme closeness of this planet to its host stars suggests that planet formation around binaries may be more robust than previously believed.

What Comes Next for This Planetary System

Researchers are eager to continue studying HD 143811 AB b. Future observations will focus on tracking the planet’s orbit more precisely and monitoring how it interacts gravitationally with the two stars. This long-term monitoring will help refine models of circumbinary planet formation and stability.

The discovery also highlights the ongoing scientific value of archival telescope data. As data analysis techniques improve and instruments become more sensitive, old observations can still yield groundbreaking discoveries. Scientists involved in this project continue to reanalyze additional datasets, suggesting that more hidden planets may still be waiting to be found.

A Broader Look at Circumbinary Planets

Circumbinary planets are no longer just science fiction. NASA’s Kepler mission previously identified several such worlds using indirect methods, but most of them orbit much farther from their stars than HD 143811 AB b. Directly imaging one that is this close to a binary pair opens a new window into understanding how diverse planetary systems can be.

This discovery reinforces a growing realization in astronomy: planetary systems are far more varied and resilient than once imagined. Even in environments dominated by competing gravitational forces, planets can form, survive, and evolve.

Research papers:

The Astrophysical Journal Letters – https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ae2007

Astronomy & Astrophysics – https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202557104