Astronomers Find a Powerful New Clue Behind Mysterious Bright Blue Cosmic Flashes

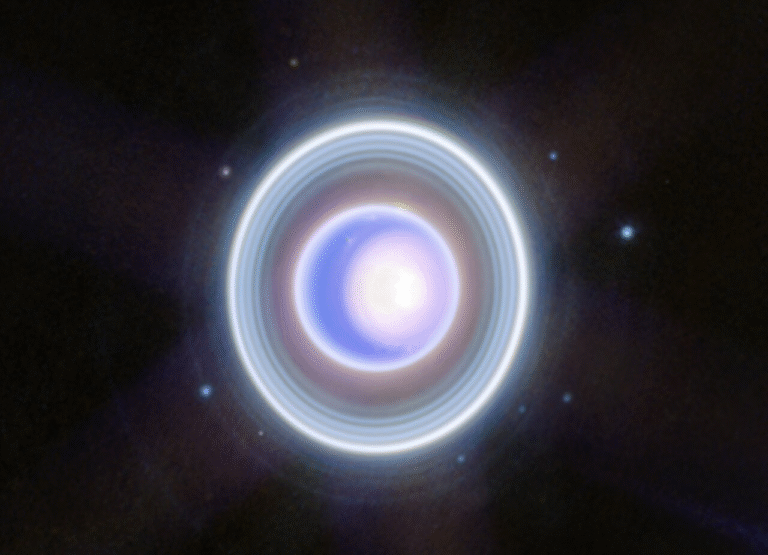

For more than a decade, astronomers have been puzzled by a strange class of cosmic explosions known as luminous fast blue optical transients, or LFBOTs. These events appear suddenly as intensely bright flashes of blue and ultraviolet light, fade within days, and often leave behind lingering X-ray and radio emissions. They are extremely rare, with only a little over a dozen discovered so far, and they do not fit neatly into any familiar category of stellar explosions.

Now, detailed observations of the brightest LFBOT ever detected, called AT 2024wpp, have provided the clearest evidence yet for what powers these extraordinary flashes. According to astronomers, these events are not unusual supernovae and are not simply gas falling into a black hole. Instead, they are likely caused by an extreme tidal disruption, where a black hole completely tears apart a massive companion star in a matter of days.

What Makes LFBOTs So Unusual

LFBOTs stand out because of a combination of extreme properties. They are incredibly luminous, visible from distances of hundreds of millions to billions of light-years, yet they last only a few days to weeks. Unlike most supernovae, which cool and redden over time, LFBOTs remain persistently blue and hot, emitting strongly in optical, ultraviolet, and X-ray wavelengths.

The first LFBOT was detected in 2014, but the best-studied early example was AT 2018cow, nicknamed “the Cow.” Since then, astronomers have identified a handful of similar events with playful nicknames such as the Koala, the Tasmanian Devil, and the Finch. Despite their whimsical names, these events represent some of the most violent and energetic phenomena known in the universe.

AT 2024wpp: The Most Extreme Example Yet

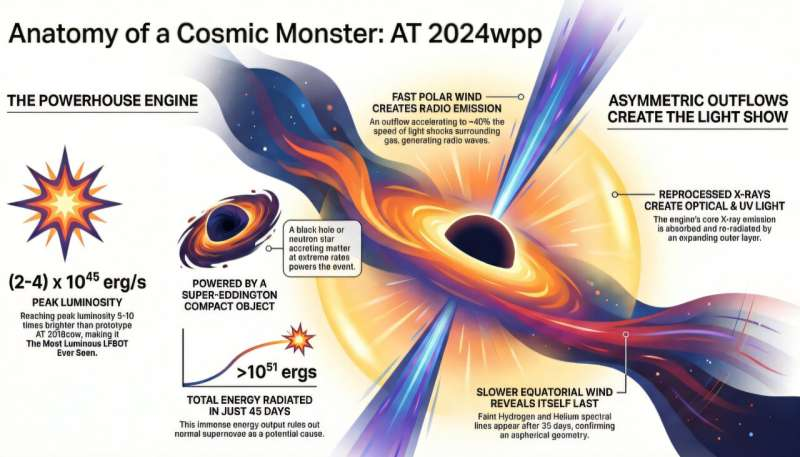

Discovered in 2024, AT 2024wpp immediately stood out. Located about 1.1 billion light-years from Earth, this event was between five and ten times more luminous than AT 2018cow, making it the most powerful LFBOT observed to date.

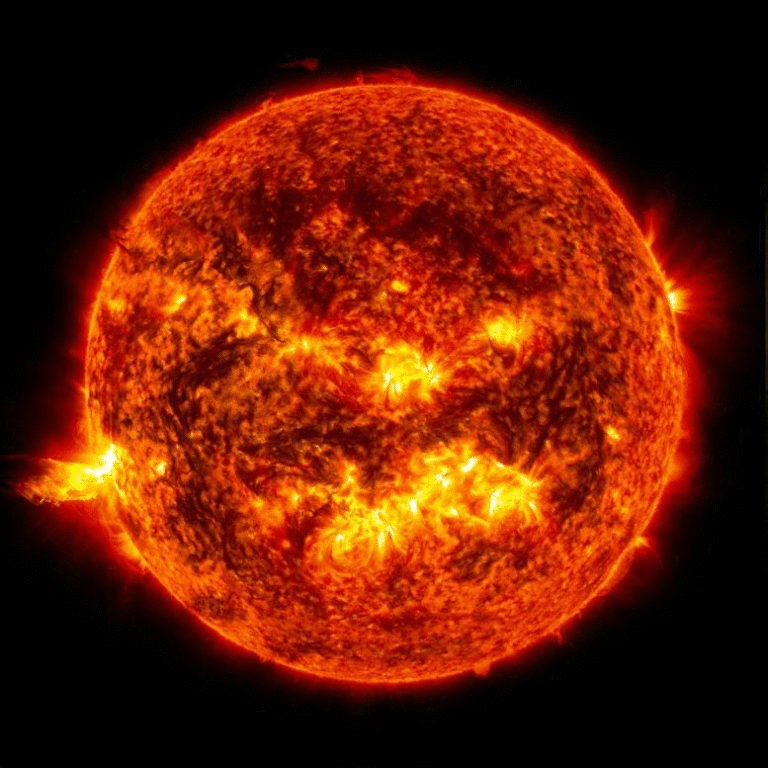

The sheer amount of energy released forced astronomers to rethink earlier explanations. Calculations showed that AT 2024wpp radiated around 100 times more energy than a typical supernova. Producing that much energy through a stellar explosion would require converting nearly 10% of the Sun’s mass directly into energy over just a few weeks, something current physics says is not realistic for any known type of supernova.

This ruled out the idea that LFBOTs are simply an exotic kind of exploding star.

A Violent Encounter With a Black Hole

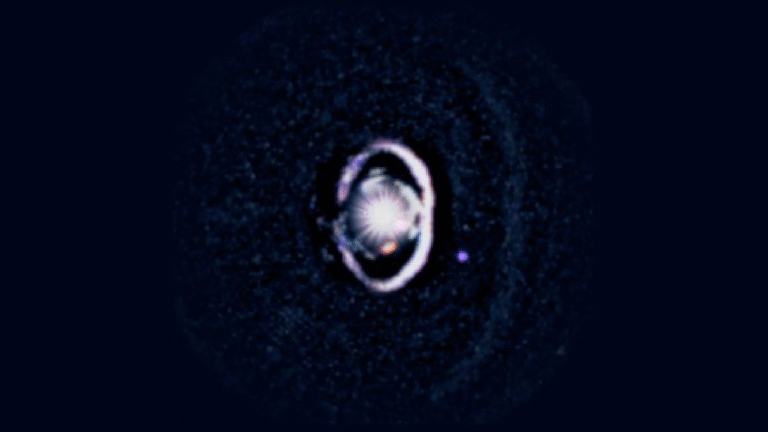

The new interpretation points to an extreme tidal disruption event involving a black hole roughly 100 times the mass of the Sun. In this scenario, the black hole and a massive companion star formed a close binary system. Over a long period, the black hole gradually siphoned material from its companion, surrounding itself with a thick cloud of gas that it could not immediately swallow.

Eventually, the companion star ventured too close. The black hole’s gravity ripped the star apart completely, shredding it in a matter of days. The newly torn stellar material slammed into the already-existing accretion disk around the black hole, releasing enormous amounts of blue, ultraviolet, and X-ray radiation.

This violent interaction explains both the extreme brightness and the rapid evolution of AT 2024wpp.

Jets, Shockwaves, and Radio Emission

The destruction of the star did not just produce light. A large fraction of the gas was funneled toward the black hole’s poles and expelled outward as powerful jets. These jets were calculated to travel at around 40% of the speed of light, making them mildly relativistic.

As the jets plowed into surrounding gas, they generated radio waves, which were detected months after the initial flash. This combination of early high-energy radiation and later radio emission matches what astronomers observed in AT 2024wpp and several earlier LFBOTs.

The Role of the Companion Star

The shredded companion star is estimated to have been more than ten times the mass of the Sun. Astronomers suspect it may have been a Wolf–Rayet star, a type of very hot, evolved star that has already lost much of its hydrogen envelope. This would explain why AT 2024wpp showed weak hydrogen emission, a feature seen in many LFBOTs.

These stars are common in actively star-forming galaxies, and AT 2024wpp fits this pattern. Like most LFBOTs, it occurred in a galaxy where young, massive stars are abundant.

Why Intermediate-Mass Black Holes Matter

The black hole involved in AT 2024wpp falls into a particularly intriguing category. Black holes with masses of tens to hundreds of solar masses are often referred to as intermediate-mass black holes, and they are notoriously difficult to study.

While gravitational wave observatories like LIGO have detected mergers involving black holes larger than 100 solar masses, astronomers have rarely observed such objects directly. Events like AT 2024wpp provide a rare opportunity to study how these black holes form, grow, and interact with massive companion stars.

By pinpointing the exact location of these events within their host galaxies, astronomers can also learn more about the stellar environments that give rise to such extreme systems.

The Telescopes Behind the Discovery

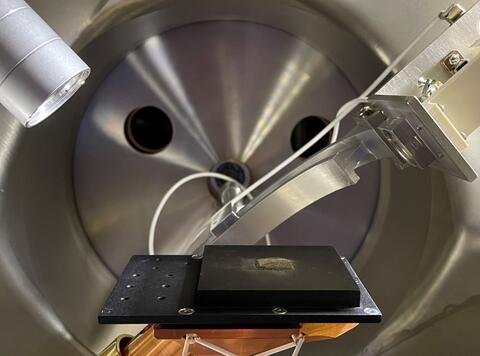

AT 2024wpp was studied using an impressive array of instruments. X-ray data came from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, Swift-XRT, and NuSTAR. Radio observations were conducted with facilities such as ALMA and the Australia Telescope Compact Array. Optical and ultraviolet measurements were gathered using Swift’s UVOT and major ground-based observatories including Keck, Lick, and Gemini.

This multi-wavelength coverage was crucial. Only by combining data across the electromagnetic spectrum could astronomers reconstruct the full physical picture of the event.

Why Future UV Telescopes Are Critical

Despite their extreme brightness, LFBOTs are hard to catch because they evolve so quickly. At present, astronomers detect only about one LFBOT per year. This is expected to change with the launch of new space-based ultraviolet observatories such as ULTRASAT and UVEX.

Because LFBOTs emit enormous amounts of UV light early on, these telescopes will be able to detect them before they reach peak brightness, allowing scientists to observe their earliest stages in detail. This will help determine whether all LFBOTs share the same origin or if multiple physical processes can produce similar-looking events.

A Broader Lesson About Cosmic Explosions

The discovery surrounding AT 2024wpp resolves a long-standing mystery but also highlights how diverse and extreme stellar deaths can be. Each catastrophic event leaves behind a distinct light signature, shaped by the physics of black holes, stellar structure, and surrounding material.

By decoding these signals, astronomers are not just solving isolated puzzles. They are testing our understanding of gravity, high-energy physics, and stellar evolution in some of the most extreme conditions the universe can offer.

Research papers:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.00952

https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.00951