Astrophysicists Use a New Patch of the Sky to Sharpen Tests of Dark Matter and Dark Energy

Astrophysicists from the University of Chicago have taken a major step forward in studying the universe’s most mysterious components by analyzing a completely new region of the sky. Using data from the Dark Energy Camera (DECam), the research team has measured subtle distortions in the shapes of more than 100 million galaxies, allowing them to probe the behavior of dark matter and dark energy with unprecedented independence from earlier surveys.

In the standard picture of cosmology, roughly 95% of the universe is invisible. About 27% is dark matter, which does not emit or absorb light but exerts gravity, while nearly 68% is dark energy, a poorly understood phenomenon responsible for the universe’s accelerating expansion. Only about 5% of the cosmos consists of ordinary matter—stars, planets, gas, and dust. Understanding how dark matter and dark energy shape the universe remains one of the biggest challenges in modern physics.

Because these components cannot be observed directly, scientists infer their properties by studying how they affect visible matter and light. The new research focuses on doing exactly that, but in a way that provides a fresh and independent test of the leading cosmological model.

Expanding Beyond the Dark Energy Survey

Between 2013 and 2019, the Dark Energy Survey (DES) mapped roughly 5,000 square degrees of the sky—about one-eighth of the full celestial sphere—using DECam mounted on the 4-meter Blanco Telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. DES measured the shapes of more than 150 million galaxies, producing some of the most influential weak gravitational lensing results to date.

However, DECam observed far more sky than the region officially included in DES. Much of this additional data came from observations taken for entirely different scientific goals, such as studying stars, dwarf galaxies, and galaxy clusters. These images were not originally intended for weak lensing analysis and were largely ignored for cosmological purposes.

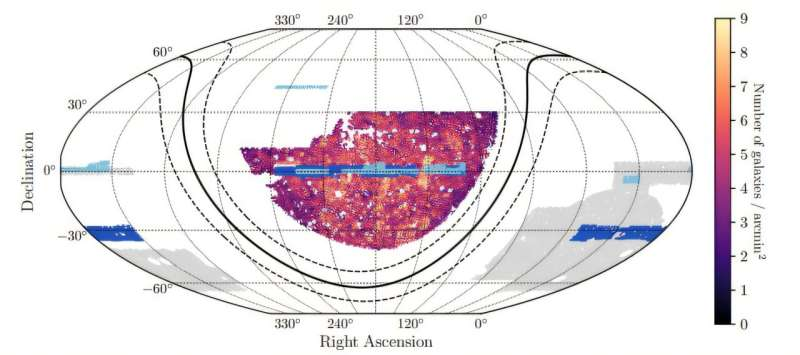

The new project, called DECADE (Dark Energy Camera All Data Everywhere), set out to change that. By carefully reanalyzing archival DECam images outside the original DES footprint, researchers were able to roughly double the number of galaxies with reliable shape measurements available for weak lensing studies.

The resulting catalog contains 107 million galaxies spread across 5,412 square degrees of sky. When combined with DES data, the total dataset reaches an impressive 270 million galaxies covering about 13,000 square degrees, or nearly one-third of the sky.

Using Weak Gravitational Lensing to Map Matter

The backbone of this work is weak gravitational lensing, a technique that measures how light from distant galaxies is slightly distorted as it passes through matter on its way to Earth. Massive structures—especially dark matter—bend spacetime, causing background galaxies to appear subtly stretched or sheared.

These distortions are extremely small and cannot be detected in individual galaxies. Instead, scientists rely on statistical analyses of millions of galaxies to detect patterns that reveal how matter is distributed throughout the universe.

Weak lensing is especially powerful because it is sensitive to all matter, not just luminous matter. This makes it one of the most direct ways to study dark matter and to test how cosmic structures grow over time under the influence of dark energy.

In the DECADE project, researchers measured galaxy shapes and also estimated galaxy distances using photometric redshifts—a method based on how much a galaxy’s light has shifted toward redder wavelengths due to cosmic expansion. With both shape and distance information, the team could model how matter clusters across vast cosmic scales.

Testing the Standard Cosmological Model

The researchers used their measurements to test the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (LCDM) model, the widely accepted framework describing the universe’s evolution. LCDM includes dark energy (represented by the cosmological constant, Lambda), cold dark matter, ordinary matter, neutrinos, and radiation.

In recent years, LCDM has faced growing scrutiny due to reported tensions between measurements of the early universe, such as those from the cosmic microwave background (CMB), and measurements of the nearby universe, including galaxy surveys and weak lensing studies. Some analyses have suggested discrepancies in how clumpy matter appears to be or how fast the universe is expanding.

The DECADE results provide an important independent check. According to the study, the growth of cosmic structure measured through weak lensing is consistent with LCDM predictions. Even more notably, when the DECADE findings are compared with constraints derived from the CMB, the results show good agreement, with no significant tension detected.

This outcome strengthens confidence in the standard cosmological model and suggests that previously reported discrepancies may be due to statistical fluctuations, data systematics, or differences in analysis methods rather than a fundamental failure of LCDM.

An Unconventional but Successful Survey Strategy

One of the most striking aspects of the DECADE project is its unconventional approach to data quality. Traditional weak lensing surveys rely on highly controlled observing strategies, often discarding large numbers of images that do not meet strict image-quality criteria.

DECADE took a different path. Because it relied on archival data collected for many purposes, the team adopted more permissive image-quality thresholds. This raised an important question: could reliable cosmological measurements still be extracted from such heterogeneous data?

The answer, demonstrated by the results, is yes. Through meticulous image inspection and extensive validation tests, the researchers showed that robust weak lensing analyses are possible even without lensing-dedicated imaging campaigns.

This finding has important implications for future surveys, particularly the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST). If more images can be used without compromising scientific reliability, future analyses could achieve higher precision than previously expected.

Why Weak Lensing Matters for Cosmology

Weak gravitational lensing has become one of the most important tools in observational cosmology. Unlike galaxy clustering or supernova measurements, lensing does not rely heavily on assumptions about how galaxies form or evolve. It directly traces the total matter distribution, making it a clean probe of fundamental physics.

Lensing measurements are especially valuable for constraining parameters related to structure growth, such as how quickly matter clumps together over cosmic time. These parameters are sensitive to both dark matter properties and the influence of dark energy.

As datasets grow larger and more precise, weak lensing is increasingly used alongside the CMB, baryon acoustic oscillations, and supernova observations to build a more complete and cross-checked picture of the universe.

A Resource for the Wider Scientific Community

The full DECADE catalog has already been released publicly and is attracting attention from researchers worldwide. Beyond cosmology, the data are being used to study dwarf galaxies, map mass distributions, and explore other astrophysical questions.

The DECADE collaboration itself includes scientists from the University of Chicago, Fermilab, the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign, Argonne National Laboratory, the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and many other institutions.

By turning overlooked archival data into a powerful cosmological tool, the project highlights how creative data reuse can unlock new scientific value—sometimes in places researchers were not initially looking.

Research Papers

The study is detailed across four peer-reviewed papers published in The Open Journal of Astrophysics:

https://astro.theoj.org/article/146158