Boiling Oceans May Exist Beneath the Ice of the Solar System’s Smallest Moons

The outer regions of our solar system are filled with icy moons that, at first glance, seem frozen, lifeless, and inactive. But new research suggests that some of these small, ice-covered worlds may be hiding something far more dynamic beneath their surfaces: liquid oceans that can actually boil. A study published on November 24, 2025, in Nature Astronomy explores how this surprising phenomenon could occur and what it means for understanding the geology of icy moons like Mimas, Enceladus, and Miranda.

For decades, scientists have suspected that several moons orbiting the giant planets host subsurface oceans. Saturn’s moon Enceladus, famous for its water plumes blasting into space, is one of the best-known examples. What this new study adds is a deeper look at how oceans behave on very small icy moons and how changes in ice thickness can dramatically alter conditions below the surface.

How Subsurface Oceans Exist on Icy Moons

On Earth, geological activity is driven by heat from radioactive elements and the movement of molten rock deep inside the planet. On icy moons, things work very differently. Their geology is powered mainly by water, ice, and gravity.

These moons experience intense tidal forces from the planets they orbit. As a moon moves through its orbit, gravitational interactions stretch and squeeze it. This constant flexing generates heat inside the moon, a process known as tidal heating. In some cases, that heat is strong enough to melt ice beneath the surface, forming a layer of liquid water between the icy shell and the rocky interior.

Importantly, this heating is not constant. The amount of tidal heating can rise and fall over long periods of time. When heating increases, the ice shell becomes thinner as more ice melts. When heating decreases, the ice shell thickens again as liquid water freezes.

Why Ice Thickness Matters More Than You Might Think

The research team, led by planetary scientist Maxwell L. Rudolph from the University of California, Davis, focused on what happens during these cycles of thickening and thinning ice shells.

In earlier work, the researchers examined what occurs when an ice shell thickens. Because ice takes up more volume than liquid water, freezing causes pressure to build. That pressure can deform the ice shell and create surface features. On Enceladus, this process may help explain the formation of the moon’s famous “tiger stripe” fractures, which release water vapor and ice particles into space.

In the new study, the researchers explored the opposite scenario: what happens when an ice shell melts from below.

As ice turns into liquid water, it becomes denser and occupies less space. This leads to a drop in pressure within the subsurface ocean. On larger moons, this pressure decrease typically causes the ice shell to crack or fail before anything more extreme happens. But on very small moons, the situation is different.

The Surprising Idea of Boiling Oceans

The researchers found that on small icy moons such as Mimas, Enceladus, and Miranda, the pressure drop from ice melting can be so large that it reaches water’s triple point. The triple point is a specific set of conditions where ice, liquid water, and water vapor can all exist at the same time.

Reaching the triple point means that the subsurface ocean can begin to boil, not because it is hot, but because the pressure becomes extremely low. This is a strange but well-understood physical process. Even cold water can boil if the pressure drops far enough.

This idea challenges the traditional view that subsurface oceans on icy moons are always calm, stable layers of liquid water. Instead, at least on smaller moons, these oceans may go through violent phase changes, producing vapor and reshaping the overlying ice shell.

Explaining the Mysteries of Miranda and Mimas

This boiling-ocean model may help explain puzzling geological features seen on certain moons.

Miranda, a small moon of Uranus, has a bizarre surface filled with sharp ridges, deep cliffs, and oval-shaped regions called coronae. These features have long been difficult to explain. According to the new research, boiling beneath the ice shell could generate stresses and deformation that produce exactly this kind of terrain.

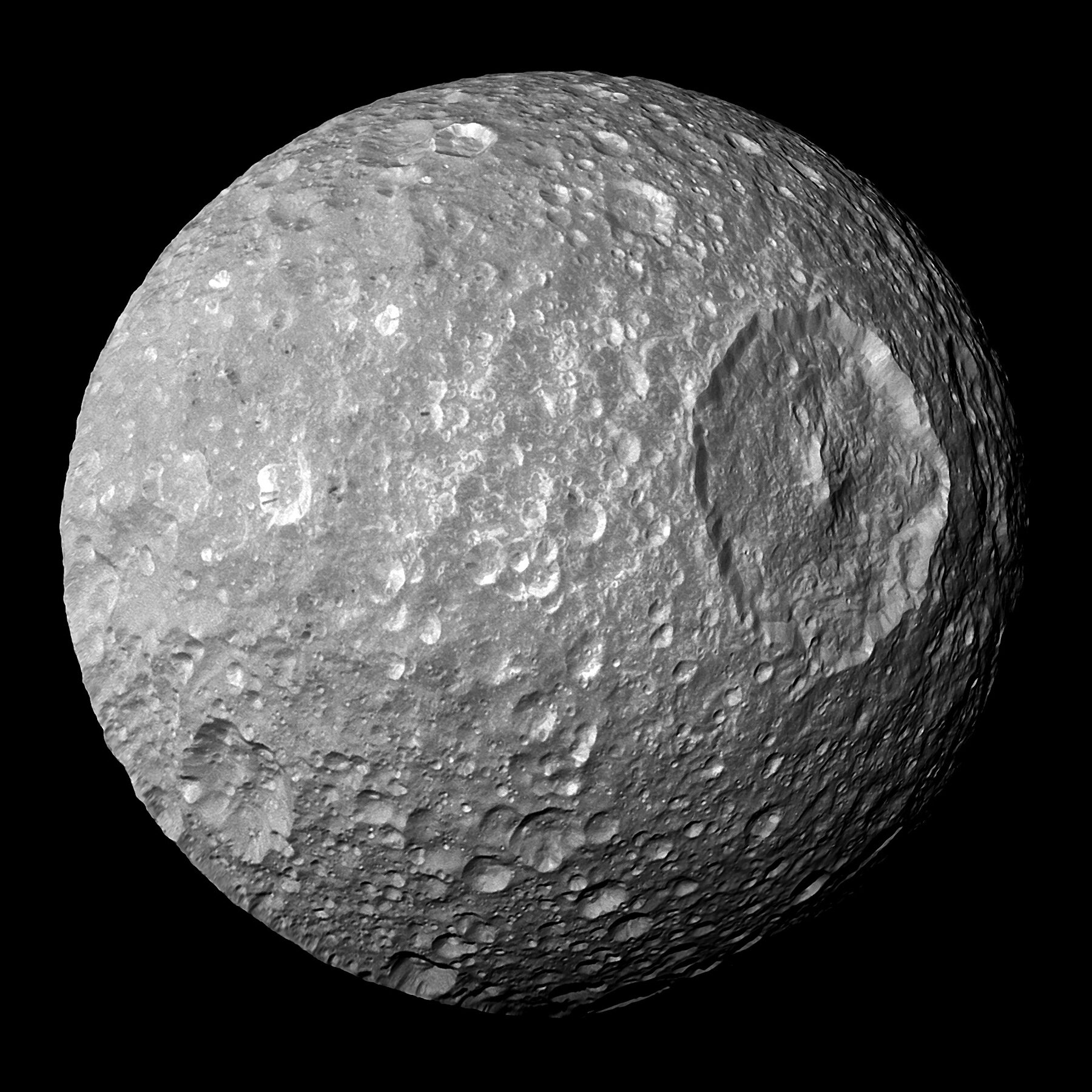

Saturn’s moon Mimas presents a different mystery. Mimas is small—less than 250 miles across—and heavily cratered, giving it the appearance of a geologically dead world. Its massive crater even earned it the nickname “Death Star” because of its resemblance to the fictional space station.

Yet measurements of Mimas’ motion show a subtle wobble that suggests a hidden ocean beneath the ice. The new study explains how Mimas can host an ocean without showing obvious surface fractures. Because its ice shell may thin without breaking, pressure can drop enough to allow boiling below while leaving the surface largely unchanged.

Why Moon Size Changes Everything

One of the key conclusions of the study is that size matters enormously when it comes to icy moon geology.

On larger icy moons such as Titania, another moon of Uranus, gravity is stronger. When ice melts and pressure drops, the ice shell tends to crack before the triple point of water is reached. This leads to surface fractures and tectonic features instead of boiling oceans.

The researchers suggest that Titania’s surface may record a history of ice shell thinning followed by thickening, producing compressional features as the ice refroze. In contrast, smaller moons cross into low-pressure regimes that allow phase changes in water to occur without catastrophic surface failure.

Why This Matters for Planetary Science and Life

Understanding how subsurface oceans behave helps scientists interpret what they see on the surfaces of distant moons. Geological features are like records of a moon’s internal history, shaped over millions or even billions of years.

These findings also matter for the ongoing search for extraterrestrial life. Liquid water is one of the key ingredients for life as we know it. Knowing which moons can sustain oceans—and how stable or unstable those oceans are—helps prioritize targets for future space missions.

Boiling does not necessarily rule out habitability. In fact, changing pressure, heat, and chemistry can create energy gradients, which are important for biological processes. However, it does suggest that the environments inside small icy moons may be more dynamic and complex than previously thought.

What This Study Adds to Our Understanding of Icy Worlds

This research highlights that icy moons cannot be treated as a single category. Their internal processes depend on size, gravity, orbital dynamics, and ice shell thickness. Even small differences can lead to dramatically different geological outcomes.

By combining physics, geophysical modeling, and observations from spacecraft like Cassini and Voyager 2, scientists are building a clearer picture of how these frozen worlds evolve. Rather than being static blocks of ice, many of them are active systems shaped by water in all its forms—solid, liquid, and vapor.