Can Philanthropy Fast-Track a Flagship Telescope Like Lazuli Space Observatory?

The idea of building a flagship-level space telescope usually comes with certain expectations: decades-long development timelines, multi-billion-dollar budgets, and layers of government oversight designed to reduce risk as much as possible. But a new proposal suggests a very different path forward. A privately funded space telescope called the Lazuli Space Observatory aims to apply the fast-moving philosophy of the commercial space sector to one of the most complex challenges in astronomy. The big question is whether philanthropy can truly accelerate a mission of this scale without sacrificing scientific ambition.

The concept is outlined in a recently released preprint paper on arXiv by researchers from Schmidt Space and several academic institutions. Schmidt Space operates under Schmidt Sciences, the philanthropic organization backed by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and his wife Wendy Schmidt. Together, they are funding Lazuli as a roughly $500 million experiment in doing flagship astronomy differently.

At its core, Lazuli is inspired by the New Space movement. This term is commonly used to describe the modern, Silicon Valley–influenced approach to space development that prioritizes speed, iteration, and cost reduction. The same mindset has helped drive down launch costs and dramatically increase the number of satellites in orbit. Lazuli’s backers believe similar principles could be applied to large space observatories, which have traditionally followed much slower and more conservative development models.

Why Flagship Telescopes Are So Expensive

To understand why Lazuli is such a radical idea, it helps to look at how major space telescopes are normally built. Government-funded observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope rely heavily on flight-proven technology. Every component must be thoroughly tested, re-tested, and validated to minimize the risk of failure, because the stakes are incredibly high when taxpayer money is involved.

This cautious approach works, but it comes at a steep price. JWST ultimately cost around $10 billion, while Roman is expected to reach about $3 billion. These observatories also take a very long time to develop. From early concept to launch, timelines of 20 to 30 years are not unusual.

Lazuli intentionally challenges this model. Because it is privately funded, it does not have to meet the same political or bureaucratic requirements. The project can accept higher levels of technical risk, something that would be far more controversial for a government agency. If something goes wrong, the financial consequences fall on its benefactors rather than the public.

What Lazuli Is Designed to Do

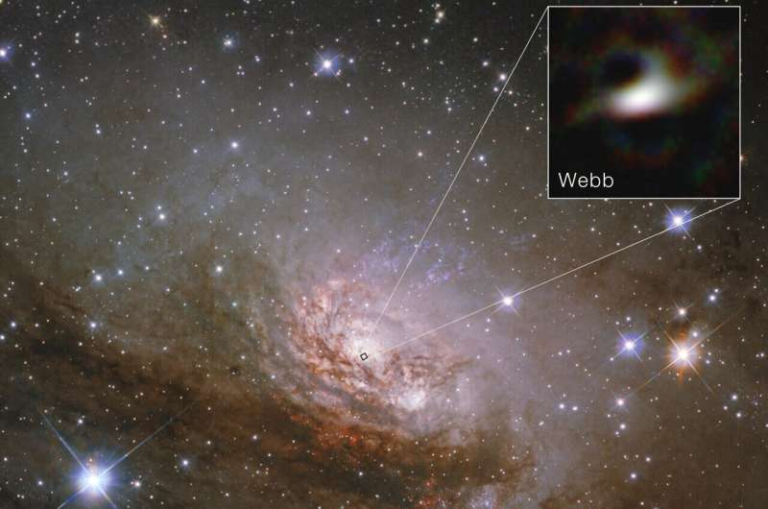

Lazuli is envisioned as a flagship-class space observatory, meaning it is comparable in scale and ambition to the largest space telescopes ever flown. In fact, it is planned to be larger than the Hubble Space Telescope, with a mirror size that puts it firmly in the top tier of astronomical instruments.

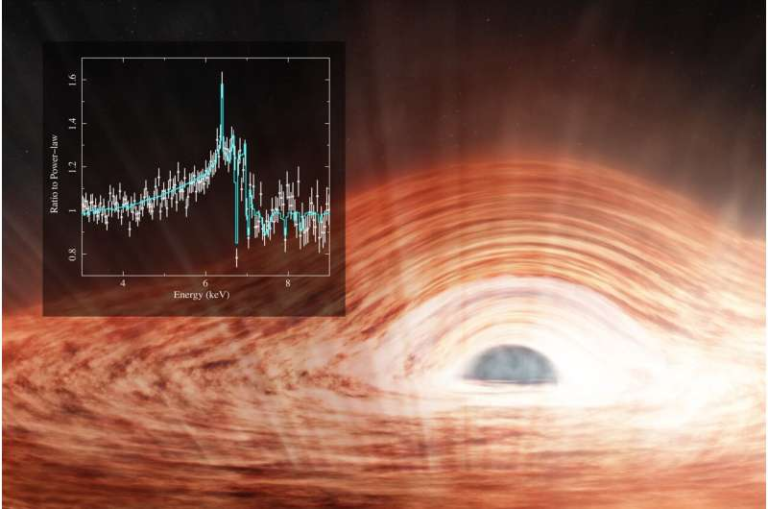

One of Lazuli’s defining features is its ability to respond rapidly to transient cosmic events. These are short-lived phenomena such as kilonovae, supernovae, and black hole or neutron star mergers that generate gravitational waves. Many of these events evolve on timescales of hours rather than days, and the earliest moments are often the most scientifically valuable.

This is where existing observatories struggle. JWST, while extraordinarily powerful, cannot slew, or rotate, quickly enough to catch many of these fleeting events before they fade. Roman, on the other hand, is optimized for wide-area surveys and does not have the resolution needed for detailed follow-up of individual objects.

Lazuli is designed to fill this gap. Its goal is to respond to a Target of Opportunity alert and reposition itself within about 90 minutes. Working alongside ground-based facilities like LIGO, which detects gravitational waves, Lazuli would be able to observe these events from space without worrying about cloud cover, daylight, or atmospheric distortion.

Instruments and Capabilities

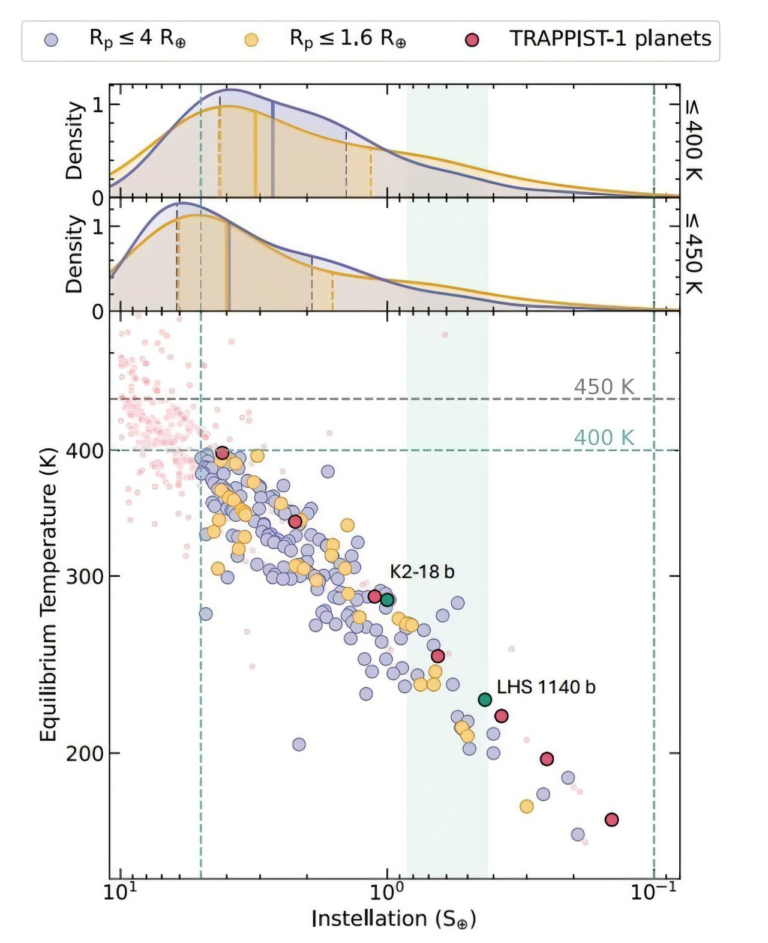

The observatory will carry a diverse set of instruments tailored to time-domain and high-contrast astronomy. One key component is the Widefield Context Camera, which uses 23 separate CMOS sensors to monitor large portions of the sky. This camera will not only provide contextual data for transient events but also detect small changes in stellar brightness that signal exoplanet transits.

In addition to detecting exoplanets, Lazuli is expected to directly image them, something that remains extremely challenging even with today’s best telescopes. To do this, it will employ a Vector Vortex Coronagraph combined with deformable mirrors. This setup can suppress starlight by a factor of up to 10 million, allowing faint planets to be seen next to their much brighter host stars.

This technology is especially notable because a similar coronagraph is planned for NASA’s future Habitable Worlds Observatory, which is still decades away from launch. Lazuli could therefore serve as a real-world technology demonstration, helping reduce risk for future taxpayer-funded missions.

Speed, Cost, and Risk

Perhaps the most striking claim made by the Lazuli team is the development timeline. The entire mission—from concept to launch—is expected to take just 3 to 5 years. For a flagship-class space telescope, this would be unprecedented. Even if the timeline slips and ends up taking twice as long, it would still represent a dramatic acceleration compared to traditional programs.

Cost control is another major focus. Around 80% of the telescope’s components are expected to be off-the-shelf hardware, rather than custom-built systems. This approach significantly reduces both cost and development time, though it also introduces additional risk.

Critics note that New Space companies are often optimistic about schedules, and large, complex projects have a habit of uncovering unexpected challenges. Still, even a partial success would provide valuable insights into how future space observatories might be built.

How Lazuli Fits Into the Bigger Picture

Lazuli is not meant to replace JWST or Roman. Instead, it is designed to complement them. JWST excels at deep, high-resolution observations of pre-selected targets, while Roman will survey vast regions of the sky. Lazuli’s strength lies in speed and flexibility, allowing it to chase events that neither of the other observatories can respond to quickly enough.

Beyond its scientific role, Lazuli is also an experiment in alternative funding models for astronomy. As flagship missions become more expensive, philanthropy may play an increasingly important role in enabling ambitious projects that would otherwise struggle to secure government approval.

Whether Lazuli becomes a landmark success or an expensive lesson remains to be seen. Either way, it represents a bold attempt to rethink how humanity builds its most powerful eyes on the universe.

Research paper reference:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.02556