Did a Rogue Planet Help Reshape the Solar System as We Know It?

For a long time, it was easy to assume that the planets in our solar system formed more or less where we see them today. But decades of research have shown that this calm picture is far from the truth. According to a new study, the giant planets—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—may have experienced a dramatic reshuffling early in the Sun’s life, possibly triggered by a close encounter with a rogue planet or low-mass brown dwarf passing nearby.

This idea adds an intriguing new twist to one of planetary science’s most important theories: the giant planet instability.

The Giant Planets Were Once Packed Much Closer Together

Scientists now believe that the four giant planets formed in a much more compact configuration than the wide spacing we see today. In their early days, these planets were locked into a delicate resonant chain, meaning their orbits were synchronized in a stable gravitational rhythm. Under normal conditions, this configuration could have remained stable for hundreds of millions of years.

Yet something clearly disrupted that balance.

Evidence across the solar system points to a period of chaos when the giant planets scattered outward to their current positions. This instability helps explain several long-standing mysteries, including Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids, the presence of irregular moons around the giant planets, and the unique orbital structures of both the asteroid belt and the Kuiper belt.

Meteorite data suggests this upheaval happened relatively early—within roughly 5 to 20 million years after the solar system formed. What remained unclear was the exact trigger.

A Passing Object From Interstellar Space

Researchers Sean Raymond and Nathan Kaib, working with the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux and the Planetary Science Institute, explored whether a close flyby from a wandering object could have started the instability.

The Sun did not form in isolation. Like most stars, it was born inside a dense stellar cluster containing hundreds or even thousands of stars. In such environments, close encounters with other stars or free-floating objects are not rare events.

To test this idea, the researchers ran 3,000 computer simulations. Each simulation began with the giant planets arranged in a resonant chain that would remain stable for over 100 million years if left undisturbed. Then, the team introduced a single flyby object and observed how the system responded.

Testing a Wide Range of Flyby Scenarios

The simulations explored a broad range of possibilities. The passing objects varied in mass from one Jupiter mass all the way up to ten times the mass of the Sun. Flyby distances ranged from 1 to 1,000 astronomical units, and encounter speeds reached up to 5 kilometers per second.

The results showed clear patterns:

- Very massive or very close flybys were too destructive, often ejecting planets entirely or leaving them on wildly distorted orbits.

- Very distant or low-impact flybys had almost no effect on the planetary system.

- Only a narrow middle range produced outcomes resembling our present-day solar system.

The Sweet Spot: Brown Dwarfs and Rogue Planets

The successful scenarios shared several key traits. The flyby object needed to have a mass between 3 and 30 times that of Jupiter, placing it squarely in the category of a low-mass brown dwarf or a free-floating planet. It also had to pass within roughly 20 astronomical units of the Sun—close enough to directly disturb the planets, not just the outer disk of debris.

Out of all 3,000 simulations, only 20 cases—less than 1%—managed to reproduce both the current orbits of the giant planets and the survival of the cold classical Kuiper belt. This group of small, distant objects has nearly circular, low-inclination orbits and is thought to preserve a pristine record of the solar system’s early days. Any viable instability model must leave this population largely intact.

How Likely Is This Scenario?

At first glance, a success rate below 1% may seem discouraging. But probability depends heavily on how common free-floating planets and low-mass brown dwarfs actually are.

Recent observations of young star clusters suggest that these wandering objects may be more abundant than traditional models predicted. If their numbers have been underestimated by even a factor of four, the probability of a flyby-triggered instability rises from about 1% to roughly 5%. In astronomical terms, that is a meaningful increase.

A Fourth Possible Trigger for Planetary Chaos

Until now, scientists have focused on three main mechanisms that could have triggered the giant planet instability:

- Gas disk dispersal, where the disappearance of the Sun’s natal gas disk destabilized planetary resonances

- Spontaneous instability, driven by slow gravitational interactions between the planets themselves

- Interactions with the outer planetesimal disk, where countless small bodies gradually altered planetary orbits

This new study introduces a fourth possibility: a close flyby from a substellar object. Importantly, the encounter itself does not need to immediately trigger chaos. The simulations show that instability could be delayed by tens of millions of years, making it difficult to distinguish this mechanism from others using geological or astronomical evidence alone.

Why Stellar Neighborhoods Matter

The Sun’s birth environment plays a crucial role in this hypothesis. Dense stellar clusters dramatically increase the odds of close encounters, not just with stars but also with rogue planets and brown dwarfs that roam freely through space.

Such flybys have already been proposed to explain other features of the solar system, including the strange orbits of distant objects like Sedna and the capture of irregular moons around the giant planets. This new work ties those ideas directly into the broader narrative of planetary migration.

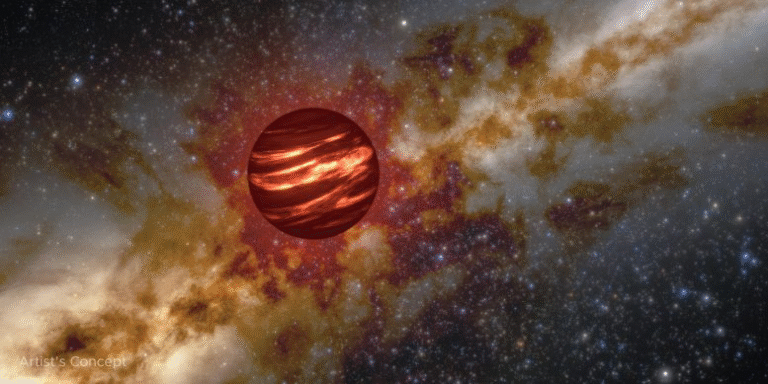

What Are Rogue Planets and Brown Dwarfs?

Rogue planets are planetary-mass objects that drift through space without orbiting a star. Some may have formed in isolation, while others were likely ejected from their original planetary systems during violent gravitational interactions.

Brown dwarfs occupy the blurry boundary between planets and stars. They are too massive to be considered planets but too small to sustain hydrogen fusion like true stars. Both types of objects are increasingly being detected in star-forming regions, strengthening the case that early solar systems faced a much busier and more chaotic neighborhood than once imagined.

What This Means for Planetary Systems Elsewhere

If a flyby can trigger large-scale rearrangements, it suggests that planetary systems may be far more sensitive to their birth environments than previously thought. Systems forming in dense clusters could experience early disruptions that permanently alter their architecture, while isolated stars may evolve more gently.

This also means that the solar system’s current layout—so familiar and orderly today—may be the result of a rare but perfectly timed encounter in its youth.

A Solar System Shaped by Chance

While this study does not overturn existing models, it adds an important piece to the puzzle. The idea that a passing rogue planet or brown dwarf helped set the stage for the solar system we see today is both scientifically plausible and deeply fascinating.

As more observations refine our understanding of free-floating planets and stellar birth environments, researchers may get closer to answering whether our cosmic neighborhood was reshaped by a brief but powerful interstellar encounter.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.07979