ESA’s Comet Interceptor Mission Plans to Chase a Comet That Hasn’t Even Been Found Yet

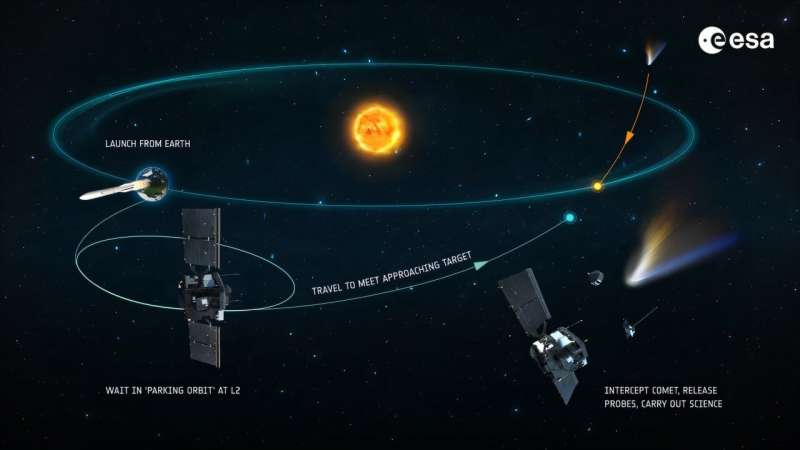

The idea of launching a space mission without knowing its final destination might sound risky, but that is exactly what the European Space Agency (ESA) is preparing to do with its ambitious Comet Interceptor mission. Instead of targeting a known comet years in advance, this spacecraft will patiently wait in space for the right object to appear, then rapidly set off to intercept it. The goal is simple but bold: study a pristine comet entering the inner solar system for the very first time, or, if fortune truly smiles, observe an interstellar visitor passing through our cosmic neighborhood.

This approach marks a major shift in how planetary science missions are planned and executed, and a new scientific study has now laid out in detail just how difficult, constrained, and fascinating this challenge really is.

What Comet Interceptor Is and Why It’s Different

Comet Interceptor, often shortened to CI, is an ESA F-class mission, meaning it is designed to be developed and launched relatively quickly and at a lower cost than flagship missions. CI is scheduled to launch in 2029, sharing a ride into space with ESA’s Ariel exoplanet mission.

After launch, CI will not immediately head toward a known target. Instead, it will travel to the Earth–Sun L2 Lagrange point, a gravitationally stable region about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth. There, the spacecraft will essentially sit and wait, sometimes for years, until astronomers discover a suitable target.

The ideal target is a Dynamically New Comet (DNC)—a comet making its first-ever journey into the inner solar system, likely originating from the distant Oort Cloud. These objects are scientifically priceless because their material has remained largely unchanged since the solar system formed over 4.5 billion years ago.

A Backup Dream: Catching an Interstellar Object

While dynamically new comets are the primary goal, Comet Interceptor could theoretically observe an interstellar object, similar to ‘Oumuamua or 2I/Borisov. These objects come from other star systems and pass through our solar system only once, never to return.

However, the chances of this happening are extremely slim. An interstellar object would need to be discovered at exactly the right time, pass close enough to Earth’s orbital plane, and move at a speed that CI could safely intercept. According to current estimates, this alignment of conditions is astonishingly unlikely, though not impossible.

The Harsh Engineering Limits of the Mission

A recent research paper by Professor Colin Snodgrass of the University of Edinburgh and his colleagues carefully examined what kinds of comets CI could realistically reach. The study highlights just how tight the mission’s constraints are.

One of the biggest limitations is delta-v, the change in velocity the spacecraft can achieve using its onboard fuel. For Comet Interceptor, this is capped at about 1.5 kilometers per second, which is modest by interplanetary standards.

The comet must also pass through a very specific region of space:

- It needs to cross between 0.9 and 1.2 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun, roughly the distance of Earth’s orbit.

- It must cross the ecliptic plane, the flat plane in which Earth and most planets orbit.

- The spacecraft must keep the Sun at an angle between 45° and 135° to ensure its solar panels function properly.

Speed is another critical issue. If the comet flyby occurs faster than 70 kilometers per second, dust particles released from the comet could severely damage or even destroy the smaller probes CI will deploy.

A Delicate Balance of Comet Activity

Not all comets are safe or useful targets. CI needs a comet that is active enough to release gas and dust, creating a scientifically interesting coma, but not so active that it becomes dangerous.

The study suggests that Halley’s Comet represents a reasonable upper limit for acceptable outgassing. Anything more intense could overwhelm the probes, while a weaker comet might not provide enough data to justify the mission.

Testing the Idea Against Real Comets

To see how realistic the mission truly is, the researchers analyzed historical comet data in two different ways.

First, they selected comets that were scientifically interesting, focusing on objects entering the solar system for the first time and reaching a brightness of magnitude 10, used as a proxy for activity. This method initially produced nine promising candidates.

Unfortunately, none of them were actually reachable. Every single one violated at least one engineering constraint, usually requiring too much delta-v or missing Earth’s orbital path by too wide a margin.

Next, the team reversed the process and filtered for feasibility first. They looked only at comets that could be reached within the 1.5 km/s delta-v limit and then checked whether those comets were active enough.

This stricter method produced just three viable candidates, all discovered within the last 25 years.

The Best Near-Miss: Comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT)

Among the feasible candidates, C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) stood out as the most interesting. Discovered in 2001, about 2.5 years before perihelion, it had strong activity and could have been intercepted within CI’s fuel budget.

The problem was speed. The flyby would have occurred at around 57 km/s, fast enough to risk damage to the probes and severely limit observation time. Even in the best-case scenario, CI would only have had a brief window to collect data.

Why Finding the Perfect Target Is Unlikely

Based on their analysis, the researchers concluded that the odds of finding an ideal comet during CI’s expected 2–3 year operational window are not great. More realistically, mission planners will have to choose a target that is simply “good enough.”

This uncertainty is an unavoidable consequence of designing a mission before the target exists. Once CI launches, the team must work with whatever nature provides, even if the comet turns out to be less active, faster, or riskier than hoped.

How LSST Changes the Game

One reason CI is still worth the gamble is the upcoming Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) at the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. LSST is expected to discover far more dynamically new comets than ever before, often years in advance of their arrival in the inner solar system.

Earlier detection gives scientists time to analyze a comet’s orbit, brightness, and potential activity, improving the odds of selecting a viable target before CI’s decision window closes.

Why Dynamically New Comets Matter

Dynamically new comets are essentially time capsules. Unlike short-period comets that have repeatedly passed near the Sun, DNCs still contain unaltered ices and dust from the early solar system. Studying them can reveal:

- How planets formed

- What materials were present in the solar nebula

- How water and organic molecules may have been delivered to Earth

A Mission Built on Patience and Probability

Comet Interceptor is a rare example of a mission built around uncertainty. It accepts risk in exchange for the chance to study something humanity has never observed up close before. Whether CI ends up visiting a faint, fragile comet or, against all odds, an interstellar traveler, the mission represents a bold experiment in how we explore space.

Sometimes, the most exciting discoveries come from simply being ready when the universe decides to send something our way.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.20521