Europa Clipper Captures Uranus Using a Star Tracker Camera During Its Long Journey to Jupiter

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission recently offered a quiet but fascinating reminder of how much science can happen even when a spacecraft is simply traveling through space. While still years away from its main destination, the spacecraft successfully captured images of Uranus using one of its star tracker cameras, turning a routine navigation test into a moment of planetary observation.

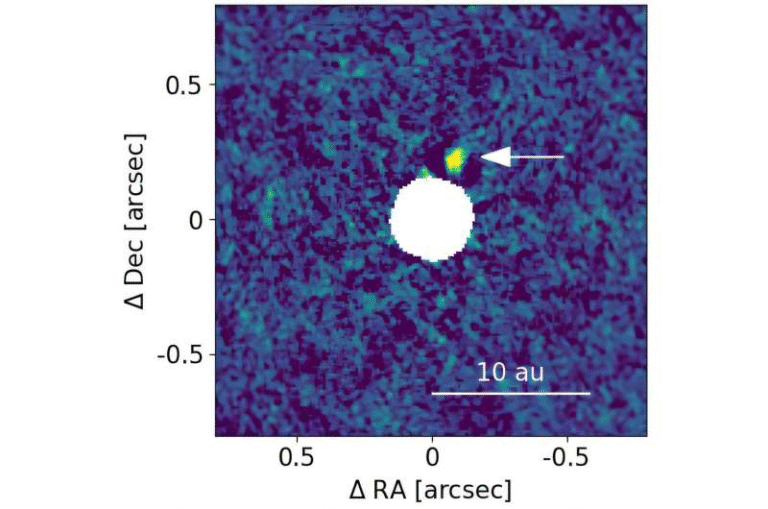

This image was taken on November 5, 2025, during Europa Clipper’s cruise phase as it continues its long journey toward the Jupiter system. The photograph shows a dense starfield, with Uranus appearing as a slightly larger, brighter dot near the left side of the frame. Though subtle at first glance, the image carries important technical and scientific meaning for the mission.

A Camera Built for Navigation, Not Photography

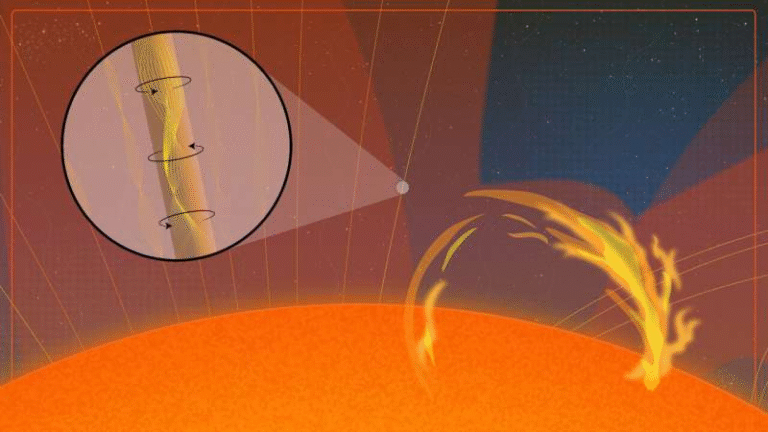

The image of Uranus was captured using one of Europa Clipper’s stellar reference units, commonly known as star trackers. These cameras are not designed for traditional science imaging. Instead, their primary job is to help the spacecraft maintain its orientation in space.

Star trackers work by continuously imaging small sections of the sky and comparing the observed star patterns with an onboard star catalog. By doing this, the spacecraft can precisely determine how it is oriented and make necessary adjustments to stay properly aligned. This function is critical for a mission like Europa Clipper, which must maintain extremely accurate pointing for its instruments, antennas, and solar arrays over a journey lasting many years.

In this case, the camera’s field of view covers only about 0.1% of the sky surrounding the spacecraft. Despite this narrow view, Uranus happened to pass through the frame during testing, making it clearly visible against the background stars.

Distance Makes the Image Even More Impressive

At the time the images were taken, Europa Clipper was approximately 2 billion miles, or about 3.2 billion kilometers, away from Uranus. From that enormous distance, the planet appears as a small dot, but still distinguishable from the surrounding stars.

NASA also released an animated GIF created from two images taken roughly 10 hours apart. In the animation, Uranus can be seen shifting slightly relative to the background stars. This apparent motion is not due to the planet racing across the sky, but rather the combined movement of Uranus and the spacecraft as they travel along their respective paths through the solar system.

This subtle motion is exactly the kind of detail star trackers are designed to detect, making the image a practical demonstration of the system working as intended.

Europa Clipper’s Current Mission Phase

Europa Clipper is currently in its interplanetary cruise phase, having launched in October 2024. The spacecraft is following a carefully planned trajectory that will eventually deliver it to Jupiter in 2030.

Rather than entering orbit around Europa, the spacecraft will conduct approximately 50 close flybys of the icy moon. This approach allows it to gather high-resolution data while minimizing exposure to Jupiter’s intense radiation environment.

The Uranus image does not represent a change in mission goals or an additional science target. Instead, it highlights how spacecraft systems are routinely tested and calibrated during long journeys, sometimes producing unexpected but valuable results along the way.

The Core Science Goals of Europa Clipper

Europa Clipper’s main objective is to determine whether Europa, one of Jupiter’s largest moons, could support life beneath its icy surface. Scientists have long suspected that Europa hides a global subsurface ocean beneath its thick shell of ice, making it one of the most promising locations to search for habitable conditions beyond Earth.

The mission is structured around three primary science goals:

- Determining the thickness of Europa’s ice shell and understanding how the surface interacts with the ocean below

- Investigating the moon’s composition, including surface materials and potential chemical ingredients necessary for life

- Characterizing Europa’s geology, including fractures, ridges, and regions where material from the ocean may have reached the surface

By addressing these objectives, Europa Clipper aims to assess the moon’s astrobiological potential rather than directly searching for life itself.

Why a Navigation Test Still Matters

Although the Uranus image was not taken by a dedicated science camera, it serves as a valuable confirmation that Europa Clipper’s navigation systems are performing reliably over extreme distances.

Deep-space missions rely heavily on autonomous systems. Communication delays can stretch from minutes to hours, meaning spacecraft must be capable of maintaining stability and orientation without constant input from Earth. A properly functioning star tracker is essential for:

- Maintaining accurate instrument pointing

- Ensuring antennas remain aligned with Earth for data transmission

- Supporting precise flybys and trajectory corrections

This successful test provides confidence that Europa Clipper will be able to execute its complex observation plan once it reaches the Jupiter system.

A Closer Look at Uranus in Passing

While Uranus was not the target of the mission, the image still adds to public interest in the distant ice giant. Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun and is best known for its extreme axial tilt, which causes it to rotate nearly on its side. This unusual orientation leads to dramatic seasonal changes that last decades.

Though Europa Clipper will not conduct follow-up observations of Uranus, moments like this highlight how spacecraft traveling through the outer solar system can occasionally capture rare perspectives of distant planets, even when science instruments are focused elsewhere.

The Value of Cruise-Phase Science and Testing

Many deep-space missions conduct extensive testing during cruise phases, long before reaching their destinations. These periods are used to:

- Calibrate instruments

- Test spacecraft subsystems under real conditions

- Validate navigation and orientation systems

- Identify and fix potential issues early

The Uranus image fits squarely within this tradition. It demonstrates that even routine operations can yield visually striking and technically meaningful results.

Looking Ahead to Jupiter and Europa

Europa Clipper’s journey is far from over. Over the next several years, the spacecraft will continue its cruise, using gravity assists and carefully timed maneuvers to reach Jupiter in 2030.

Once there, the mission will begin one of the most detailed explorations ever conducted of an icy moon. Data collected by Europa Clipper is expected to shape planetary science for decades, refining our understanding of ocean worlds and the conditions that may allow life to exist beyond Earth.

The brief glimpse of Uranus serves as a reminder that space missions often deliver moments of discovery long before their primary science even begins.

Research reference:

https://science.nasa.gov/mission/europa-clipper/