Evidence From Bleached Clay Rocks Suggests Ancient Mars Once Had a Rain-Driven Climate

White, bleached rocks scattered across the dusty red surface of Mars are offering some of the strongest evidence yet that the planet was once far warmer and wetter than it is today. New findings from NASA’s Perseverance rover suggest that parts of Mars may have experienced sustained rainfall and humid conditions, potentially similar to tropical climates on Earth, billions of years ago.

The discovery centers on unusual light-colored rocks found in Jezero crater, the landing site of the Perseverance rover. These rocks stand out sharply against the surrounding reddish terrain and are composed of aluminum-rich kaolinite clay, a mineral that is extremely difficult to form without long-lasting exposure to water.

What Makes These Rocks So Important

Kaolinite is not just any clay. On Earth, it typically forms when rocks and sediments are exposed to intense chemical weathering caused by persistent rainfall over thousands to millions of years. In many cases, kaolinite is associated with warm, humid, tropical environments, such as rainforests, where constant water flow leaches away most other minerals.

Finding kaolinite on Mars is significant because modern Mars is cold, dry, and largely inhospitable to liquid water at its surface. The presence of this mineral strongly suggests that Mars once had far more water circulating through its environment than it does today.

The kaolinite rocks discovered by Perseverance range in size from small pebbles to larger boulders and appear scattered across the rover’s exploration path. These are not part of a visible, continuous rock layer but rather isolated fragments, often referred to as “float rocks,” resting on the surface.

How Perseverance Identified the Kaolinite

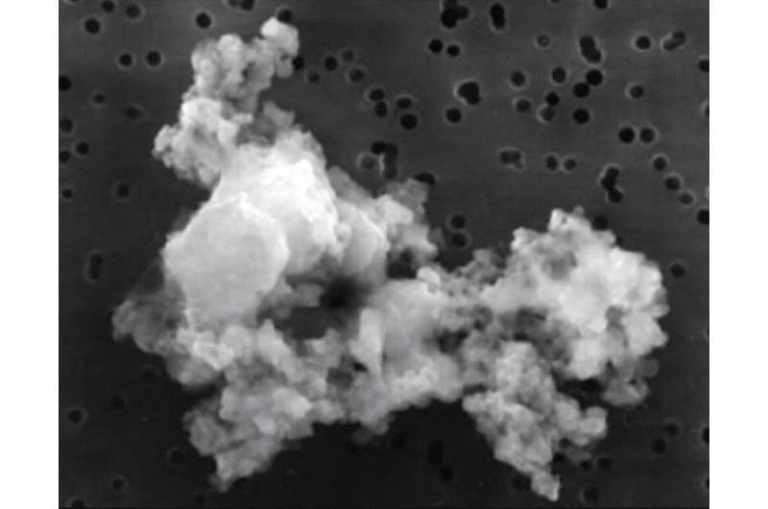

NASA’s Perseverance rover used its onboard instruments, including SuperCam and Mastcam-Z, to analyze the composition and appearance of these rocks. By comparing the spectral signatures of the Martian samples with known Earth rocks, scientists were able to confirm that the light-colored fragments were indeed rich in kaolinite.

To strengthen their conclusions, researchers compared the Martian rocks with kaolinite samples collected from Earth, including sites near San Diego, California, and regions in South Africa. These Earth samples formed under well-understood environmental conditions, allowing scientists to directly evaluate how similar formation processes might have occurred on Mars.

The results showed a close match between the Martian rocks and Earth kaolinite formed through low-temperature, rainfall-driven chemical weathering, rather than through volcanic or hydrothermal activity.

Ruling Out Other Formation Scenarios

Kaolinite can also form in hydrothermal systems, where hot water alters rocks underground. However, this process leaves behind a different chemical signature than rainfall-driven weathering. To test this possibility, the research team analyzed data from three different geological datasets, comparing hydrothermal kaolinite formation with the Martian samples.

The chemical evidence from Jezero crater did not align with hydrothermal alteration. Instead, it strongly pointed toward long-term exposure to surface water, consistent with rainfall or sustained water flow at relatively low temperatures.

This distinction is crucial because it suggests that Mars did not just experience isolated wet events, such as volcanic heating or short-lived floods, but may have supported stable, long-lasting wet climates.

Jezero Crater’s Watery Past

Jezero crater itself plays an important role in this discovery. Billions of years ago, the crater contained a lake roughly twice the size of Lake Tahoe, fed by rivers that formed a large delta. This lake environment made Jezero an ideal location to search for signs of past water activity and potential habitability.

One mystery remains: the exact origin of the kaolinite fragments. There is no large kaolinite outcrop visible near where the rocks are currently found. Scientists are exploring several possibilities. The rocks may have been transported into the crater by rivers, washed downstream and deposited in the lake basin. Another possibility is that they were ejected by meteorite impacts from distant locations and scattered across Jezero’s surface.

Satellite imagery has identified large kaolinite outcrops in other regions of Mars, but Perseverance has not yet reached those locations. For now, these scattered surface rocks provide the only direct, ground-level evidence of how such minerals formed on Mars.

What This Means for Mars’ Climate History

The discovery adds weight to a growing body of evidence that ancient Mars was not uniformly cold and dry. Instead, the planet may have gone through extended periods of warm, wet conditions, with rainfall playing a significant role in shaping its surface.

Many previous findings pointed to lakes, rivers, and groundwater on Mars. However, kaolinite formed by rainfall suggests something even more Earth-like: a functioning hydrological cycle, where water evaporated, condensed, and fell back to the surface as rain over long periods of time.

This challenges simpler models of Mars’ climate and suggests the planet may have been capable of supporting stable surface water for millions of years, rather than only brief wet episodes.

Implications for the Search for Life

Water is one of the most fundamental requirements for life as we know it. On Earth, environments with abundant liquid water and chemical stability are often rich in biological activity. The potential existence of rain-fed, humid environments on Mars raises intriguing questions about whether life could have once emerged or survived there.

Rocks like kaolinite act as geological time capsules, preserving chemical information from billions of years ago. If life ever existed on Mars, environments shaped by rainfall would have been among the most habitable places for it to thrive.

This is one reason Jezero crater was chosen as Perseverance’s landing site. The rover’s ongoing mission includes collecting samples that may eventually be returned to Earth, allowing scientists to analyze Martian materials with far greater precision.

Why Kaolinite Is Rare and Valuable on Mars

Kaolinite is considered one of the hardest clay minerals to form, even on Earth. It requires not just water, but a lot of it, acting over long time periods. Its presence on Mars therefore represents some of the strongest mineralogical evidence yet for a warm and wet ancient climate.

Elsewhere on Mars, orbital instruments have detected clays, but surface-level confirmation like this is rare. These small, bleached rocks may seem unremarkable at first glance, but scientifically, they are among the most informative materials the rover has encountered so far.

As Perseverance continues its journey, scientists hope to identify the source of these kaolinite fragments and learn even more about the environmental conditions that shaped early Mars.

Looking Ahead

This discovery does not just tell us that Mars once had water. It suggests that the planet may have experienced complex, Earth-like weather systems, including rainfall, capable of reshaping landscapes over geological timescales.

Understanding how Mars transitioned from a potentially habitable world to the cold, dry planet we see today remains one of the biggest questions in planetary science. Each new finding, including these bleached kaolinite rocks, helps fill in another piece of that puzzle.

For now, these pale stones scattered across Jezero crater stand as quiet but powerful reminders that Mars was once a very different world.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02856-3