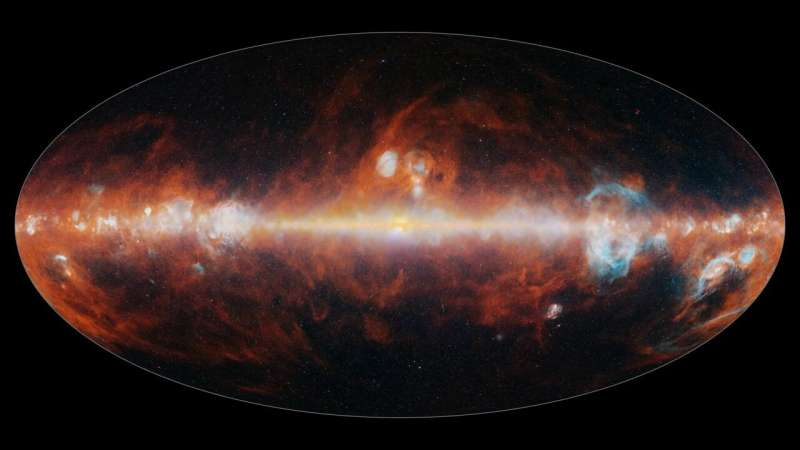

First Sky Map From NASA’s SPHEREx Observatory Reveals the Entire Universe in 102 Infrared Colors

NASA has reached a major milestone with its SPHEREx Observatory, releasing the first-ever full-sky map created in 102 distinct infrared wavelengths. The image, made public in December 2025, represents a new way of looking at the universe—one that goes far beyond what human eyes can see and opens the door to answering some of the most fundamental questions in modern cosmology.

At first glance, the map looks like a colorful, abstract portrait of the sky. But every color carries meaning. The blues, greens, and whites primarily highlight stars, bright and hot across multiple infrared bands. Shades of blue also trace hot hydrogen gas, while deep reds reveal cosmic dust, the raw material from which stars and planets form. This is not a decorative image; it is a densely packed scientific dataset that captures the entire sky in extraordinary spectral detail.

What makes this achievement especially important is not just the coverage of the whole sky, but the number of infrared “colors” involved. Previous all-sky surveys typically worked with a handful of infrared bands. SPHEREx uses 102 separate wavelengths, allowing scientists to detect subtle differences in how objects emit and absorb infrared light. These differences help identify what objects are made of, how far away they are, and how they have changed over time.

Infrared light itself is invisible to the human eye, but it is everywhere in the cosmos. Many of the universe’s most important processes—such as star formation, galaxy growth, and the movement of cosmic dust—are best observed at infrared wavelengths. By mapping the entire sky in this way, SPHEREx provides a new foundational dataset that researchers will rely on for decades.

One of the central scientific goals of SPHEREx is to study the earliest moments of the universe. Scientists believe that a dramatic event known as cosmic inflation occurred an incredibly tiny fraction of a second after the Big Bang. During this period, space itself expanded at an extraordinary rate, leaving behind subtle imprints in the large-scale structure of the universe. By mapping the positions and distances of hundreds of millions of galaxies, SPHEREx will help researchers understand how that early event shaped the three-dimensional distribution of matter we see today.

This is where the 102 infrared wavelengths become especially powerful. By measuring how galaxy light is stretched, or redshifted, as it travels through expanding space, SPHEREx can estimate distances across vast cosmic scales. The result is not just a flat image of the sky, but a true 3D map of the universe, showing how galaxies are arranged across billions of light-years.

Beyond probing the early universe, SPHEREx will also shed light on how galaxies evolve over nearly 14 billion years. Galaxies today look very different from their younger counterparts. Some are actively forming stars, while others are quiet and aging. Infrared observations are key to understanding these changes because they can peer through dust that blocks visible light and reveal hidden star-forming regions. With repeated scans of the entire sky over its mission lifetime, SPHEREx will track how galaxies grow, interact, and transform.

Closer to home, the observatory will also explore our own Milky Way galaxy. One of its objectives is to map the distribution of water, organic molecules, and cosmic ices—ingredients considered essential for life as we know it. These materials are found in cold regions of space, such as molecular clouds and protoplanetary disks, where new stars and planets are born. Infrared wavelengths are particularly sensitive to these substances, making SPHEREx an ideal tool for studying the chemical building blocks of planetary systems.

The way SPHEREx collects its data is just as impressive as the science it enables. The spacecraft orbits Earth in a Sun-synchronous low-Earth orbit, allowing it to maintain a consistent orientation relative to the Sun. As it circles the planet, SPHEREx scans strips of the sky from north to south. Over time, as Earth moves around the Sun, these strips shift, eventually covering the entire sky. The observatory captures thousands of images every day, gradually assembling them into a complete all-sky map.

To achieve its 102-color view, SPHEREx uses six detector arrays, each equipped with specialized filters that split incoming infrared light into multiple wavelength bands. Each array covers 17 wavelengths, and together they form the full spectral range of the mission. This design allows SPHEREx to perform spectral mapping on an unprecedented scale, combining imaging and spectroscopy into a single, efficient survey.

Importantly, this first sky map is only the beginning. During its planned two-year primary mission, SPHEREx is expected to scan the entire sky multiple times. Each new pass will improve the sensitivity of the data, revealing fainter objects and finer details. By stacking these maps together, scientists can reduce noise and uncover signals that would otherwise remain hidden.

Another notable aspect of the SPHEREx mission is its commitment to open science. The data collected by the observatory will be made publicly available, allowing researchers around the world to explore the dataset and pursue their own scientific questions. This openness ensures that the mission’s impact will extend far beyond its original goals, supporting discoveries that may not yet even be imagined.

To better understand why SPHEREx matters, it helps to compare it with earlier missions. Telescopes like WISE and Planck also mapped the sky in infrared and microwave wavelengths, but with far fewer spectral bands. SPHEREx fills a crucial gap between broad imaging surveys and targeted, high-resolution observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope. While Webb looks deeply at small regions of space, SPHEREx provides the big-picture context, showing where interesting objects are located across the entire sky.

In many ways, SPHEREx is designed to be a cosmic reference map. Astronomers studying galaxies, stars, or planetary systems can use its data to place their observations in a broader framework. The mission’s combination of full-sky coverage, spectral richness, and repeated observations makes it a uniquely powerful tool for modern astronomy.

The release of the first SPHEREx sky map marks a turning point. It demonstrates that the observatory is working as intended and already delivering on its ambitious promise. More importantly, it provides scientists with a new lens through which to explore the universe—from the earliest moments after the Big Bang to the chemical ingredients of life in our own galaxy.

As additional maps are completed and released, SPHEREx is poised to become one of the most widely used datasets in astrophysics. This first image is not just a snapshot of the sky; it is the foundation of a mission that aims to connect cosmic history, galaxy evolution, and the origins of life into a single, coherent picture.

Research reference: https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.4872