Five Newly Confirmed Exoplanets Put Their Atmospheres to the Ultimate Test

One of the most exciting goals of modern astronomy is finding planets beyond our solar system that might have atmospheres—and, if conditions are right, maybe even the ingredients needed for life. This is a major reason why the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) exists. Its incredible sensitivity allows scientists to study the thin layers of gas surrounding distant worlds. But before JWST can analyze an atmosphere, astronomers first need to find planets that actually have one.

That turns out to be harder than it sounds.

Although scientists have identified around 6,000 exoplanets so far, many of them are unlikely to hold onto atmospheres. Others are far larger than Earth, making them less useful for studying rocky, potentially Earth-like worlds. And in many cases, the stars they orbit are simply too bright, drowning out the faint atmospheric signals astronomers are trying to detect.

That’s why a newly published study describing five newly confirmed exoplanets, some of which may still retain atmospheres, is drawing significant attention. The research, led by Jonathan Gomez Barrientos of Caltech, focuses on small planets orbiting M-dwarf stars, which are among the most promising targets for atmospheric studies.

How These Five Planets Were Found and Confirmed

The story begins with NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). TESS scans large portions of the sky, looking for tiny dips in starlight that occur when a planet passes—or transits—in front of its host star. When TESS spots a promising signal, it issues what’s known as a TESS Object of Interest (TOI) alert, flagging the object as a potential planet.

However, a TOI is only a candidate. Confirming that it’s truly a planet—and not a false signal caused by stellar activity or background stars—requires extensive follow-up observations.

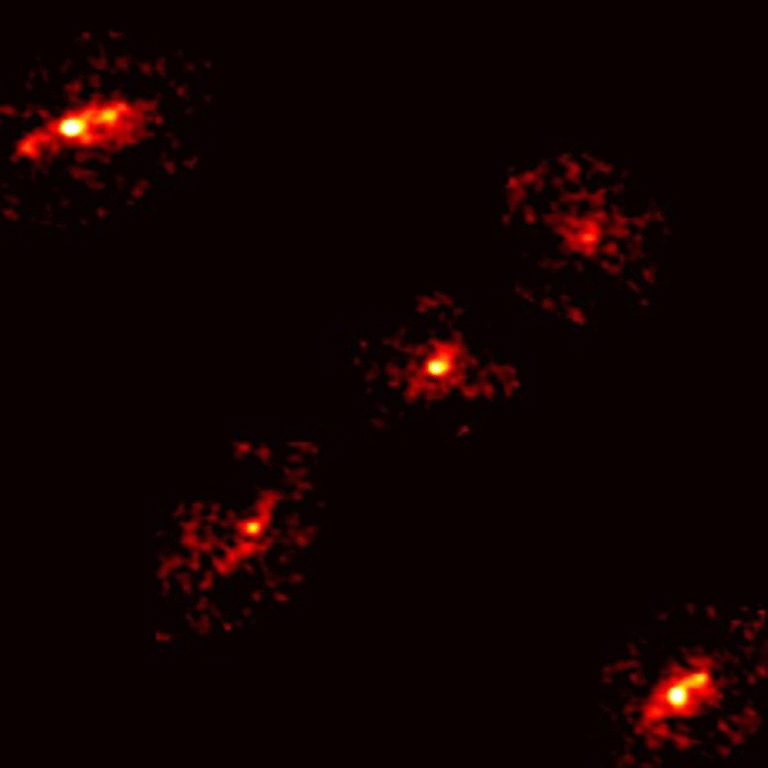

In this case, confirmation was a major collaborative effort. Scientists combined data from at least nine different telescopes, including powerful facilities like the Keck II Observatory and the Hale Telescope. These follow-up observations involved techniques such as transit photometry and high-resolution imaging, allowing the team to rule out alternative explanations and firmly confirm the planets’ existence.

The result: five planets across four planetary systems, with one system hosting two planets locked in orbital resonance, meaning their gravitational interactions keep their orbits in a stable, repeating pattern.

A Closer Look at the Planets Themselves

All five planets fall into the category of small exoplanets, which makes them especially valuable for atmospheric studies.

- Four of the planets are Super-Earths, with sizes ranging from 1.28 to 1.56 times Earth’s radius.

- The fifth planet, TOI-5716b, is particularly interesting because it is roughly Earth-sized, placing it among the smaller rocky planets known to orbit M-dwarf stars.

Their orbital periods range from an incredibly short 0.6 days to a still-rapid 11.5 days. While these orbits are much shorter than Earth’s 365-day year, such tight orbits are common among currently detectable exoplanets. Short periods make planets easier to observe repeatedly, which is crucial when telescope time is limited.

Perhaps most importantly, all five planets orbit M-dwarf stars—small, cool, and relatively dim stars that make up the majority of stars in our galaxy.

Why M-Dwarf Stars Are Both Helpful and Hazardous

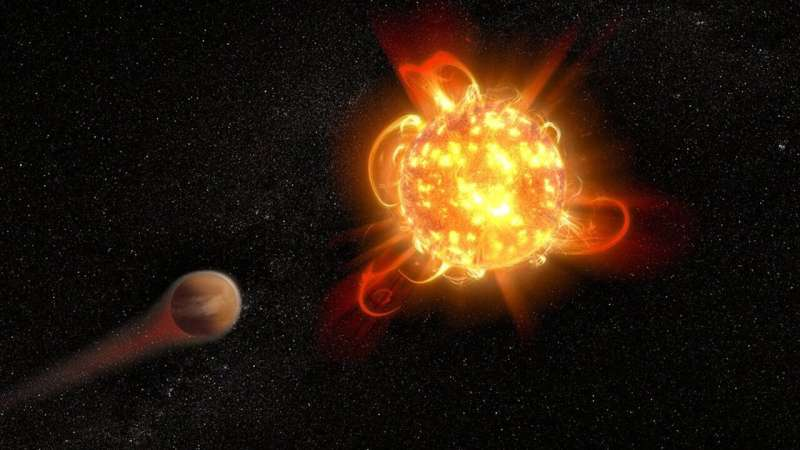

M-dwarf stars are a double-edged sword when it comes to planetary atmospheres.

On the positive side, their low brightness makes it easier for telescopes like JWST to isolate the faint atmospheric signals of orbiting planets during transits. Simply put, there’s less starlight to overwhelm the planet’s atmospheric fingerprint.

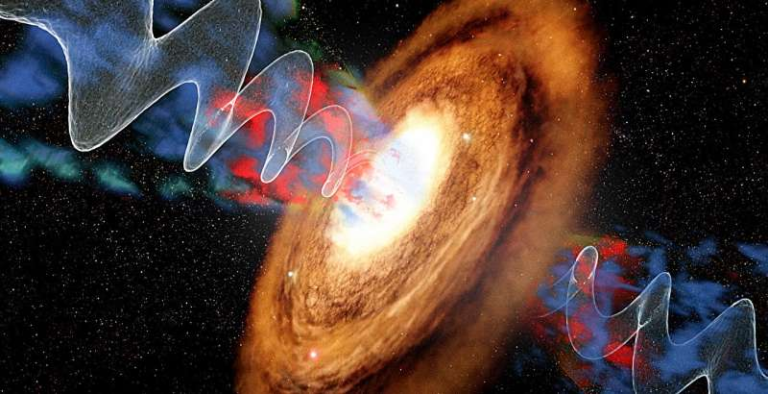

However, M-dwarfs are also known for being highly active and volatile, especially when they’re young. They frequently emit intense X-ray and ultraviolet flares, which can batter nearby planets. Over time, this radiation can strip away atmospheres, particularly for planets that orbit close to their stars.

This raises a critical question: which planets can hold onto their atmospheres, and which ones lose them entirely?

The Cosmic Shoreline and Atmospheric Survival

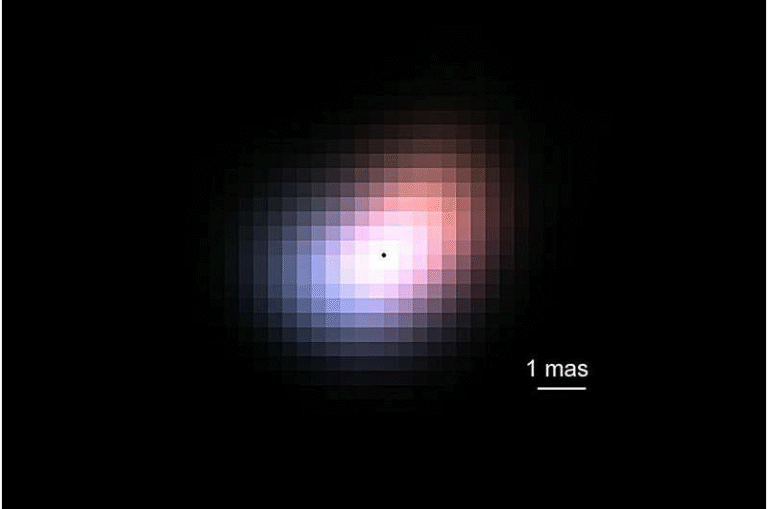

To answer that question, astronomers use a concept known as the cosmic shoreline. This idea plots a planet’s stellar radiation exposure (insolation) against its gravity.

- Planets receiving high radiation are more likely to lose their atmospheres.

- Planets with strong gravity, usually due to higher mass, are better at holding onto their gaseous envelopes.

When these factors are plotted together, a surprisingly clear boundary emerges—the cosmic shoreline. Planets above this line are likely atmosphere-free, while those below it may retain atmospheres, at least partially.

In the new study, the five planets fall into three distinct categories based on this framework.

Which of the Five Planets Might Have Atmospheres?

According to the analysis:

- Three of the planets lie well above the cosmic shoreline, suggesting that intense stellar radiation has probably stripped away any atmospheres they once had.

- TOI-5736b, the planet with the shortest orbital period, occupies a category of its own. Despite being bombarded by radiation, its large size and mass mean it could theoretically retain a volatile-rich, heavy atmosphere—though this remains uncertain.

- The most intriguing case is TOI-5728b.

Despite orbiting an active M-dwarf star, TOI-5728b appears to sit in a region where its gravity may be sufficient to counteract atmospheric loss. Combined with its host star’s low brightness, this makes TOI-5728b an excellent candidate for follow-up observations with JWST.

Habitability: Realistic Expectations Matter

While the possibility of detecting an atmosphere is exciting, scientists are careful not to overstate the chances of life.

With an 11.5-day orbital period, TOI-5728b orbits very close to its star, making Earth-like conditions unlikely. Surface temperatures and radiation levels would probably be extreme by human standards. That said, researchers don’t rule out the potential for extremophiles—organisms capable of surviving in harsh environments—especially if the planet has protective atmospheric or geological features.

Ultimately, the only way to know is to observe the planet directly.

Why This Discovery Matters for Exoplanet Science

This study highlights how modern exoplanet science works as a step-by-step pipeline:

- Discovery by wide-field surveys like TESS

- Confirmation using multiple ground-based telescopes

- Physical and atmospheric characterization

- Targeted follow-up with flagship observatories like JWST

Each step narrows down the most promising targets, ensuring that precious telescope time is used effectively.

Even though JWST is extremely busy, planets like TOI-5728b are exactly the kind of worlds astronomers hope to study in detail. Detecting or ruling out an atmosphere on such a planet would provide valuable insights into atmospheric erosion, planetary evolution, and the limits of habitability around small stars.

For planetary scientists and astrobiologists alike, these five newly confirmed worlds represent more than just additional dots on a star map. They are natural laboratories, helping researchers understand why some planets cling to their atmospheres while others lose them to space.

As observations continue and JWST eventually turns its gaze toward these systems, the answers may take time—but that patient, methodical progress is exactly how science moves forward.

Research paper:

Jonathan Gomez Barrientos et al., From Earths to Super-Earths: Five New Small Planets Transiting M Dwarf Stars, arXiv (2025).

https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2512.11971