Frequent Flares From the TRAPPIST-1 Star Could Seriously Shape the Habitability of Its Planets

The star known as TRAPPIST-1 has been a favorite target for astronomers ever since scientists discovered that it hosts seven Earth-sized planets, several of them located in what is considered the habitable zone. But new research suggests that this small star’s volatile personality may be making life much harder for those nearby worlds.

A recent study led by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder takes the most detailed look yet at the physics behind TRAPPIST-1’s frequent stellar flares. These energetic outbursts, which occur about six times a day, release powerful radiation that could play a decisive role in determining whether any of the system’s planets can hold onto atmospheres—or support conditions suitable for life.

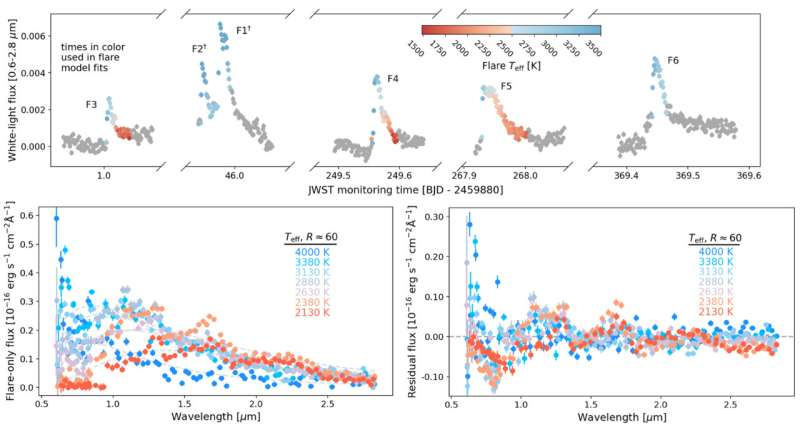

The findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and rely heavily on observations from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), combined with advanced computer modeling of stellar flare physics.

What Makes TRAPPIST-1 So Special

TRAPPIST-1 is a small, ultracool red dwarf star located about 40 light-years away in the constellation Aquarius. It has less than 10% the mass of the Sun and is only slightly larger than Jupiter, yet it packs an extraordinary planetary system around it.

All seven of its planets are similar in size to Earth, and three of them orbit within the star’s habitable zone, where surface temperatures could theoretically allow liquid water. That alone makes TRAPPIST-1 one of the most promising systems in the search for life beyond our solar system.

However, size is not everything. Red dwarf stars like TRAPPIST-1 are known for their intense magnetic activity, and this star is no exception.

A Star That Flares Constantly

Astronomers have long known that TRAPPIST-1 is highly active, but the new study reveals just how frequent and disruptive its flares really are. These flares are sudden bursts of energy caused by magnetic processes in the star’s atmosphere, and they release radiation across a wide range of wavelengths.

For scientists trying to study the atmospheres of TRAPPIST-1’s planets, this constant activity is a major obstacle. During planetary transits—when a planet passes in front of the star and blocks a tiny fraction of its light—large flares can overwhelm or distort the signal, making it difficult to separate what belongs to the planet from what comes from the star itself.

Early observations of TRAPPIST-1 did not fully anticipate just how often these flares would interfere with transit data, complicating efforts to study planetary atmospheres using powerful tools like JWST.

How Stellar Flares Actually Work

To understand what TRAPPIST-1’s flares mean for its planets, researchers needed to look beyond simple brightness measurements and dig into the physical mechanisms driving these events.

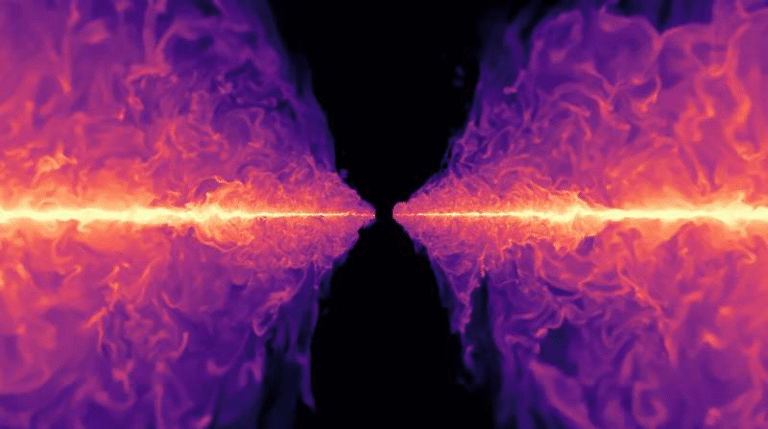

All stars are surrounded by magnetic fields that twist, stretch, and tangle over time. In stars like TRAPPIST-1, these magnetic fields can become so stressed that they suddenly snap and reconnect, releasing stored energy in a violent burst.

When this happens, high-energy electron beams are launched downward into the star’s atmosphere. As these electrons collide with ultra-hot plasma, they heat it rapidly, causing the plasma to glow and emit radiation. That glow is what astronomers detect as a stellar flare.

Using JWST data from six individual flares observed in 2022 and 2023, the research team applied a new grid of advanced flare models to reconstruct what kind of electron beams must have triggered each event.

Surprisingly Weak, But Still Dangerous

One of the study’s most surprising findings is that TRAPPIST-1’s flares appear to be weaker than expected when compared to flares from similar stars. The electron beams responsible for these flares were roughly ten times less powerful than those typically seen in other active red dwarfs.

That might sound like good news—but it does not mean the planets are safe.

Even relatively “weak” flares still generate visible light, ultraviolet radiation, and X-rays, all of which can significantly affect planetary atmospheres over time. When flares happen repeatedly, day after day, the cumulative impact can be severe.

What This Means for TRAPPIST-1’s Planets

Based on their models, researchers suspect that the innermost planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system have likely been stripped of their atmospheres entirely. Continuous exposure to flare-driven radiation would make it extremely difficult for these worlds to retain gases, leaving behind bare, rocky surfaces.

Planets farther out may have fared better, especially those in the habitable zone. One planet in particular, TRAPPIST-1e, stands out as a potential survivor. Some data suggest it may still retain a thin, possibly Earth-like atmosphere, although this remains uncertain and will require more observations to confirm.

Understanding how flares affect atmospheric chemistry is especially important because radiation can break apart molecules, alter chemical balances, and influence whether potential biosignatures could exist—or be detected at all.

Why JWST and Flare Modeling Matter

One major benefit of this research is methodological. By using computer models to simulate flare physics, scientists can separate flare signals from planetary signals in observational data. This allows for more accurate interpretations of what JWST is seeing when it studies exoplanet atmospheres.

Instead of treating flares as unwanted noise, researchers can now reverse-engineer them, predicting how much radiation they produce at different wavelengths and how that radiation interacts with nearby planets.

This approach opens the door to more precise studies not only of TRAPPIST-1, but of other flare-active stars that host potentially habitable planets.

Why Red Dwarf Stars Pose a Habitability Puzzle

Red dwarfs are the most common type of star in the Milky Way, which makes them extremely important in the search for life. However, their planets tend to orbit very close to them in order to stay warm enough for liquid water. That closeness exposes planets to strong magnetic activity and frequent flares.

This creates a delicate balance. On one hand, red dwarfs offer long lifespans and stable energy output over billions of years. On the other hand, their early and ongoing activity may erode atmospheres before life has a chance to take hold.

TRAPPIST-1 is now one of the best real-world laboratories for testing how that balance plays out.

Looking Ahead

The study marks an important step toward understanding how stellar behavior shapes planetary environments. As JWST continues to observe TRAPPIST-1 and similar systems, combining observational data with detailed flare modeling will be crucial.

Whether any of TRAPPIST-1’s planets can truly be considered habitable remains an open question. What is clear, though, is that the star’s frequent flares are not just a curiosity—they are a central factor in determining the fate of its planets.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ae1960