Gaia Data Suggests a Supernova May Have Passed Dangerously Close to Earth 10 Million Years Ago

Scientists are piecing together evidence that a nearby supernova explosion may have influenced Earth around 10 million years ago, during the late Miocene epoch. A recent study published in Astronomy & Astrophysics combines geological data from Earth’s oceans with precise stellar motion measurements from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission, offering one of the most detailed investigations yet into whether an ancient stellar explosion left a measurable mark on our planet.

At the center of this research is a mysterious spike in an isotope called beryllium-10 (10Be) found in deep-sea samples from the central and northern Pacific Ocean. This anomaly has intrigued scientists for years, and the new study explores whether a supernova occurring relatively close to Earth could be responsible.

Why Beryllium-10 Matters

Beryllium-10 is a cosmogenic isotope, meaning it forms when cosmic rays collide with atoms in Earth’s atmosphere. These high-energy particles originate from powerful astrophysical sources, including supernova explosions. Once created, 10Be falls to Earth’s surface and eventually settles into sediments, ice cores, or ocean crusts, where it can be measured millions of years later.

What makes 10Be especially useful is its half-life of about 1.39 million years. This allows scientists to trace changes in cosmic ray intensity over geological timescales. An unusually high concentration of 10Be can indicate a period when Earth was bombarded by more cosmic rays than usual, potentially due to a nearby astrophysical event.

In this case, researchers identified elevated levels of 10Be in Pacific Ocean ferromanganese crusts that date to between 9.0 and 11.5 million years ago, with a clear peak around 10 million years ago.

Using Gaia to Look Back in Time

To investigate what might have caused this anomaly, the research team turned to Gaia Data Release 3 (DR3), one of the most detailed star catalogs ever created. Gaia has mapped the positions, motions, and distances of over 1.8 billion stars, making it possible to reconstruct how stars and star clusters moved through space millions of years ago.

The scientists compared the timing of the 10Be spike with the past locations of thousands of open star clusters. These clusters are particularly important because they contain massive stars that end their lives as supernovae.

By modeling the orbits of both the Sun and these star clusters backward in time, the team estimated the probability of a supernova occurring close enough to Earth during the relevant period.

How Close Could the Supernova Have Been?

The study found that the 10Be anomaly could be explained by a supernova that exploded between 35 and 100 parsecs from Earth. To put that in perspective, that range corresponds to roughly 114 to 326 light-years away.

At around 35 parsecs, the probability of such an event is small but not zero. As the distance increases toward 70–100 parsecs, the probability becomes significantly higher. Within this range, cosmic rays from a supernova could plausibly reach Earth in sufficient numbers to explain the observed increase in 10Be.

Two star clusters stand out as the most promising candidates:

- ASCC 20, which dominates the probability of a nearby supernova up to about 70 parsecs

- OCSN 61, which becomes more relevant beyond 70 parsecs

Both clusters are linked to the broader Orion star-forming region, an area that was much closer to the Solar System 10 million years ago than it is today.

Earth’s Proximity to the Orion Region

One of the key insights from the study is the Solar System’s changing position within the Milky Way. Around 10 million years ago, Earth was likely closer to active star-forming regions, including Orion. These regions are rich in massive, short-lived stars, making them prime locations for supernova explosions.

This proximity increases the plausibility that Earth experienced enhanced cosmic radiation from a nearby stellar death during the late Miocene.

What Would a Nearby Supernova Do to Earth?

Distance is everything when it comes to supernova impacts. Astronomers estimate that supernovae occurring more than 150 parsecs (about 489 light-years) away pose no serious threat to life on Earth.

However, at closer distances, the effects become more interesting and potentially more disruptive. A supernova within tens to a hundred parsecs would not instantly wipe out life, but it could lead to:

- Increased cosmic ray bombardment

- Long-term radiation exposure lasting 10,000 to 100,000 years

- Changes in atmospheric chemistry, including possible ozone depletion

- Subtle but global geological and climatic effects

The study does not claim that the 10-million-year-old event caused mass extinctions or dramatic biological upheaval. Instead, it suggests that Earth may have experienced a prolonged period of elevated radiation, detectable today through isotopic signatures like 10Be.

How This Fits with Other Supernova Evidence

This possible late Miocene supernova is not the only one scientists have identified through geological records. Previous studies have found clear evidence of nearby supernovae using iron-60 (60Fe), another radioactive isotope produced almost exclusively in stellar explosions.

Notable events include supernovae that occurred around 2.6 million years ago and between 6 and 8 million years ago. Together, these findings suggest that Earth has encountered the effects of nearby supernovae multiple times during its recent geological past.

Could There Be Other Explanations?

The researchers are careful not to claim a definitive answer. While a nearby supernova is a viable explanation, other possibilities remain.

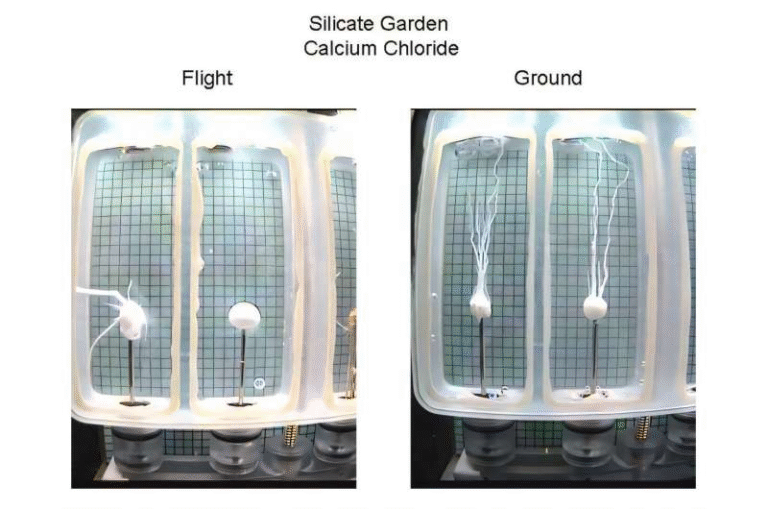

One alternative is that the 10Be anomaly reflects regional oceanographic processes rather than a global cosmic event. Changes in ocean circulation could concentrate 10Be in the Pacific basin without requiring a supernova.

Another possibility involves variations in the heliosphere, the magnetic bubble created by the solar wind. If the Solar System passed through a denser interstellar environment, cosmic rays could have penetrated more easily, increasing 10Be production without a supernova.

To resolve this, scientists emphasize the need for additional 10Be records from other parts of the world, including different oceans and terrestrial archives. A global signal would strongly support an astrophysical origin, while a localized one would point toward Earth-based processes.

Why This Research Matters

Understanding how supernovae interact with Earth has implications far beyond this single study. It helps scientists:

- Reconstruct the history of cosmic events near our planet

- Understand how astrophysical processes influence climate, atmosphere, and life

- Improve models of Milky Way star formation

- Inform the search for life on other planets, where nearby supernovae could play a role in habitability

This research sits at the crossroads of astrophysics, geology, atmospheric chemistry, climate science, biology, and cosmochemistry, highlighting how interconnected these fields truly are.

Looking Ahead

The Gaia mission continues to refine our understanding of stellar motions, and future geological measurements will add more data points to Earth’s cosmic history. Together, they may soon confirm whether a supernova truly lit up the skies near Earth 10 million years ago—or whether another, more subtle process was at work.

For now, the evidence suggests that Earth’s story is deeply intertwined with the life and death of stars, even on timescales that stretch far beyond human imagination.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556253