Halloween Fireballs Could Bring an Elevated Cosmic Impact Risk in 2032 and 2036, Scientists Say

Every late October and early November, the Taurid meteor shower puts on one of the most captivating sky shows of the year. The slow, glowing meteors—sometimes called Halloween fireballs—radiate from the constellation Taurus and are fragments shed by Comet Encke. But according to new research, these pretty streaks might hint at something more serious: an increased risk of atmospheric explosions or cosmic impacts in the years 2032 and 2036.

The Study That Raised Eyebrows

The research, led by Mark Boslough, a physicist and research professor at the University of New Mexico, was presented at the 2025 Planetary Defense Conference in Cape Town, South Africa, and published in Acta Astronautica. The paper, titled “2032 and 2036 Risk Enhancement from NEOs in the Taurid Stream: Is There a Significant Coherent Component to Impact Risk?”, explores the potential for larger near-Earth objects (NEOs) hidden within the Taurid stream.

The study proposes that certain years—specifically 2032 and 2036—may bring Earth closer to what’s known as a Taurid Resonant Swarm (TRS), a dense cluster of debris that could include objects big enough to cause local or regional damage if they strike or explode in the atmosphere.

What Exactly Is the Taurid Resonant Swarm?

The Taurids are the result of Comet Encke slowly disintegrating, leaving a trail of dust, pebbles, and rocks that Earth crosses twice each year. The nighttime Southern and Northern Taurids peak around Halloween, while the Beta Taurids occur during the day in June and are typically invisible.

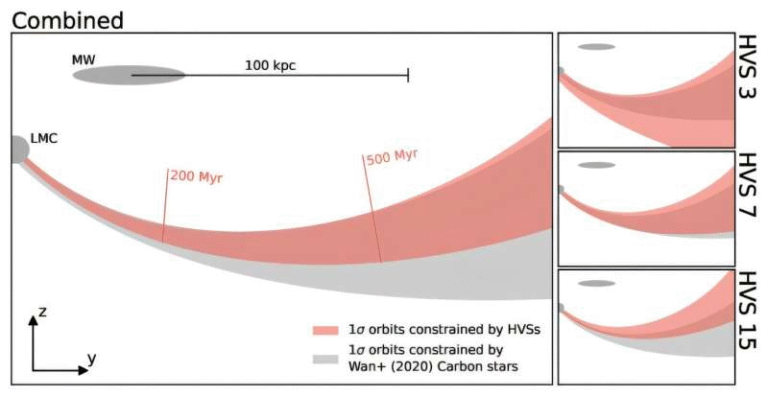

However, not all parts of this debris stream are the same. The new research focuses on a “resonant swarm”, a gravitationally trapped cluster of debris caused by Jupiter’s pull. Objects in this resonance orbit the Sun seven times for every two Jupiter orbits, concentrating them periodically in specific regions of space.

When Earth’s orbit intersects those dense clusters, it could encounter larger fragments—objects tens of meters wide—capable of producing airbursts (massive explosions in the atmosphere) like those seen in Chelyabinsk (2013) and Tunguska (1908).

Why 2032 and 2036 Matter

Boslough’s team found that the Taurid swarm’s orbit may bring a dense concentration of debris close to Earth in the years 2032 and 2036.

In 2032, the potential swarm would approach from Earth’s nighttime side, meaning any fireballs would be visible. In 2036, the swarm would approach from the sunward direction, making it much harder to detect visually unless the objects were extraordinarily bright.

If the hypothetical swarm does exist, Earth could temporarily face a higher-than-average impact risk. The researchers emphasize, however, that even an “enhanced” risk still means the overall probability of an impact remains low—just slightly elevated compared to baseline cosmic hazards.

How Dangerous Could It Be?

The study focuses on airburst-sized NEOs, objects large enough to explode in the atmosphere but not necessarily make it to the ground. These can still be powerful enough to cause significant local damage.

- The Chelyabinsk meteor in 2013 exploded with an estimated 0.5 megaton yield (roughly 30 times the Hiroshima bomb) and injured about 1,500 people—mostly from flying glass when they ran to windows after seeing a bright flash.

- The Tunguska event in 1908 released an estimated 3–5 megatons, flattening trees across 800 square miles in Siberia.

If a similar event occurred over a populated region, such as New Mexico, the primary injuries would again likely come from shattered glass and blast waves rather than direct impact.

The takeaway? The odds of a dangerous Taurid object hitting Earth are low, but the potential energy involved means it’s worth paying attention to.

Detecting and Preparing for the Swarm

One of the most encouraging points of the study is that we already have the technology to detect and track such objects if we know when and where to look. Telescopes could perform targeted sky surveys in 2032 and 2036 to determine if a Taurid Resonant Swarm truly exists.

The upcoming NEO Surveyor telescope—a NASA infrared mission scheduled to launch in the late 2020s—could play a major role in identifying potentially hazardous objects early enough for mitigation.

Mitigation strategies include deflection missions (like NASA’s DART test in 2022) or civil defense measures if impact avoidance isn’t possible. Knowing about a swarm well in advance would dramatically increase the world’s readiness.

Cutting Through the Misinformation

Boslough has long worked to debunk asteroid and airburst myths circulating online. He has corrected past claims that misunderstood impact science—including one suggesting an ancient Jordanian city was destroyed by a Tunguska-scale airburst, which was later retracted.

He also co-authored a paper refuting the fringe theory that the Taurid swarm triggered a climate catastrophe 12,900 years ago. His point is clear: while asteroid impacts are a legitimate natural hazard, misinformation about them often makes the threat seem exaggerated or mystical.

Reliable research—like this new Taurid analysis—helps clarify where the real risks lie and what science-based steps can be taken.

Taurids, Fireballs, and the Science of Airbursts

When small Taurid fragments hit Earth’s atmosphere, they burn up, creating those glowing streaks we call meteors. Larger ones—meters to tens of meters across—can survive deeper into the atmosphere, compressing air ahead of them until they explode in a fireball.

These airbursts occur when the object’s internal strength can no longer withstand atmospheric pressure. The resulting shockwave releases massive energy, as seen in the Chelyabinsk and Tunguska examples.

What makes the Taurids interesting is their low entry speed (compared to other meteor showers), which produces bright, slow-moving fireballs. That’s why the Taurids are called “Halloween fireballs”—they linger in the sky, glowing orange and golden.

Some planetary defense experts believe studying Taurids could reveal much about how near-Earth objects behave when entering our atmosphere and how we can model and prepare for future impacts.

When and How to Watch the Taurids

If you’re planning some skywatching, the Taurid meteor shower peaks around Halloween through early November. The best viewing is after 2 a.m. from dark-sky locations, when the Taurus constellation is high in the sky.

After the next full moon on November 5, the skies will be darker—perfect for catching those long, glowing streaks. Even without a swarm approaching, this shower often produces occasional bright fireballs, making it a favorite among stargazers.

The Bigger Picture of Planetary Defense

The research reminds us that planetary defense isn’t science fiction—it’s an active, international effort involving surveys, modeling, and mitigation strategies.

In New Mexico, facilities like the Magdalena Ridge Observatory and the Los Alamos and Sandia National Laboratories play important roles in observing, modeling, and planning for asteroid threats.

The 2032 and 2036 Taurid swarm windows are a test of our preparedness. Whether or not the swarm exists, these years offer a valuable opportunity for science to learn more about near-Earth debris and how our planet can stay safe.

As Boslough puts it, being aware of cosmic hazards is part of being responsible citizens of Earth. The same way we prepare for earthquakes, wildfires, or hurricanes, we can prepare—rationally and calmly—for celestial events.