Hidden Stars Are Changing How Scientists Search for Alien Technology in the Milky Way

The search for intelligent life beyond Earth has always depended on where we choose to look. A new scientific study suggests that astronomers may have been overlooking a vast number of potential targets—not because they were careless, but because many stars are effectively hidden in plain sight. By accounting for these unseen stars, researchers believe we can significantly improve how we search for technosignatures, the possible signs of advanced extraterrestrial civilizations.

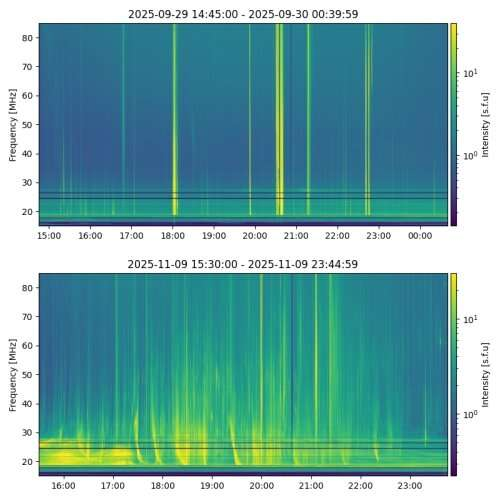

The study, recently published as a preprint on arXiv, explores how simulated star populations can reshape the way scientists interpret data from radio SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) surveys. Instead of focusing only on stars listed in well-known catalogs, the researchers show that radio telescopes are unintentionally surveying millions of additional stars every time they point at the sky. This overlooked population could play a crucial role in determining how common—or rare—technological civilizations really are.

What Are Technosignatures and Why Do They Matter?

Technosignatures are detectable signs of technology that could indicate the presence of intelligent life beyond Earth. The most familiar example is artificial radio transmissions, but technosignatures can take many forms. These include optical or infrared lasers, large-scale engineering projects like Dyson spheres, unusual atmospheric pollutants, or excess waste heat that cannot be explained by natural processes.

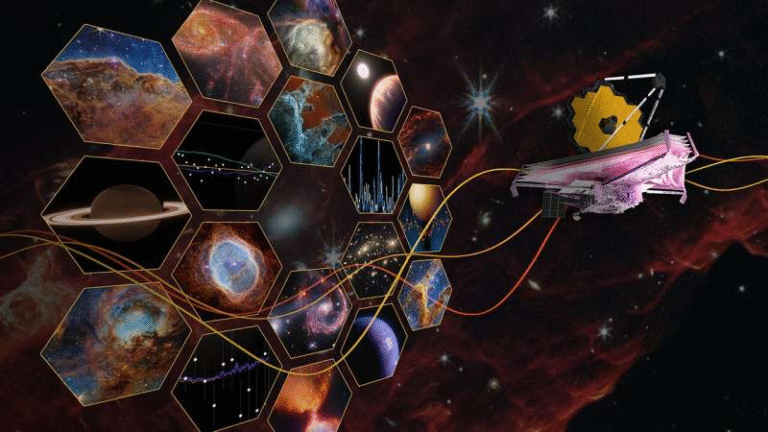

Radio technosignatures remain a major focus because radio waves travel vast distances through space and are relatively easy to detect with current technology. Large-scale projects such as Breakthrough Listen, launched in 2015, use some of the world’s most powerful radio telescopes to scan nearby stars and galaxies for artificial signals.

However, interpreting the results of these searches depends heavily on how many stars are actually being observed—and that number has been underestimated.

The Problem with Traditional Star Catalogs

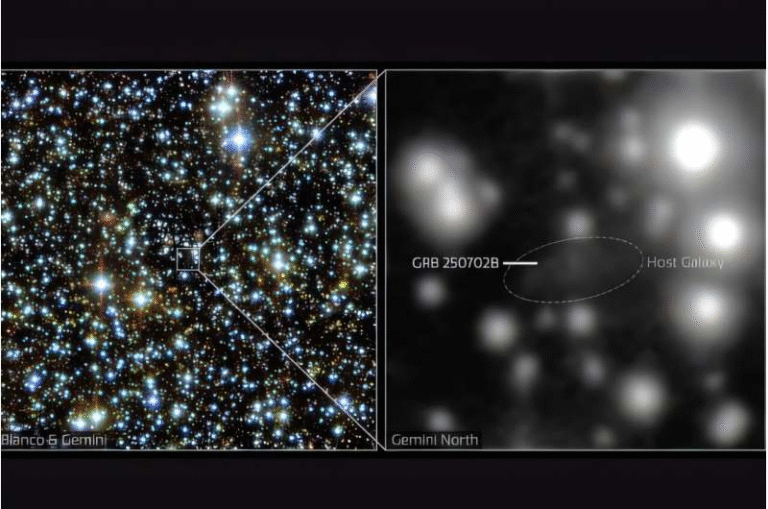

Most SETI surveys rely on stellar catalogs created by missions like Gaia, Kepler, and TESS to decide which stars are being observed. While these surveys are incredibly detailed, they are still incomplete. Some stars are too faint, too distant, or located in crowded regions of the Milky Way where detection becomes difficult.

This creates a bias. If astronomers only count cataloged stars, they may assume they have searched fewer stellar systems than they actually have. As a result, estimates about how rare technological civilizations might be could be skewed.

This is where the concept of stellar bycatch comes in.

Understanding Stellar Bycatch

When a radio telescope observes a specific target, its field of view is often quite large. Within that beam lie many other stars that were not the intended targets but are still being observed at the same time. These stars are known as stellar bycatch.

The new study focuses on identifying and quantifying this bycatch using a powerful simulation tool called the Besançon Galactic Model (BGM). This model recreates the Milky Way’s stellar population by accounting for star types, distances, brightness, motions, and spatial distribution throughout the galaxy.

By simulating where stars actually are—not just where catalogs say they are—the researchers were able to estimate how many stars truly fall within the field of view of radio SETI observations.

What the Researchers Found

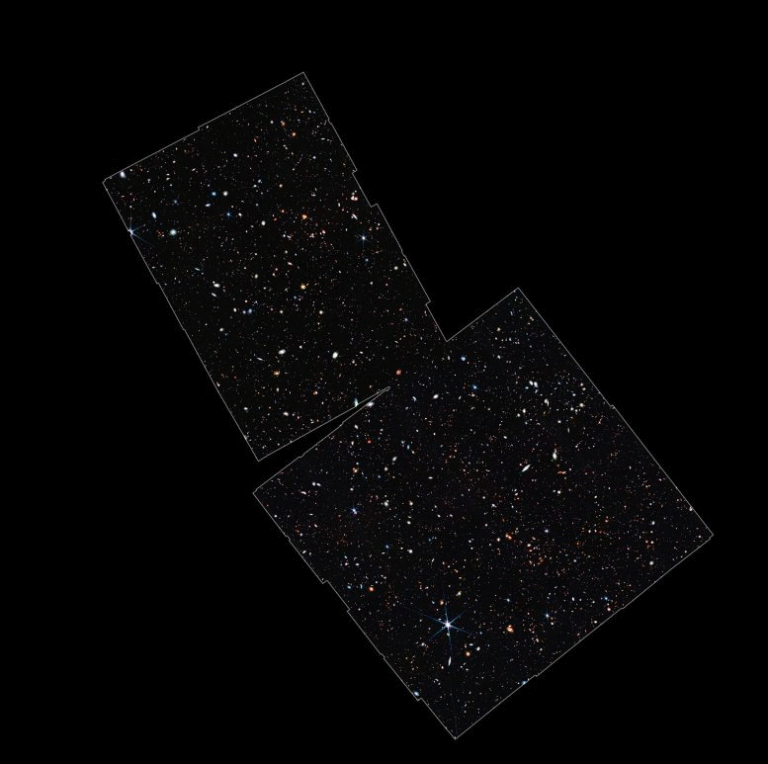

Applying this method to past Breakthrough Listen radio surveys, the team found something remarkable. Instead of surveying tens of thousands of stars, these observations likely included millions of stars when stellar bycatch is taken into account.

Specifically, the simulations suggest that approximately 6.18 million stars were included across 1,229 radio telescope pointings, extending out to distances of nearly 25 kiloparsecs, which covers much of the Milky Way galaxy.

This dramatically increases the effective sample size of SETI searches and allows scientists to place much stronger constraints on how common extraterrestrial transmitters might be.

Stronger Limits on Alien Transmitters

Using the expanded star count, the researchers calculated new upper limits on the prevalence of persistent radio transmitters. Their results suggest that fewer than about 0.001 percent of stellar systems within roughly 2.5 kiloparsecs host a continuously active, powerful radio transmitter detectable by current surveys.

This does not mean intelligent life is rare in the universe. Instead, it shows that loud, continuous radio transmitters—the kind easiest for us to detect—are uncommon in our galactic neighborhood. Advanced civilizations may communicate differently, transmit intermittently, or use technologies we have not yet learned how to detect.

Reducing Human Bias in SETI

One of the most important contributions of this study is its ability to reduce human selection bias. Traditionally, astronomers choose which stars to observe based on assumptions about which systems are most likely to host life. By including stellar bycatch, SETI surveys become more agnostic and comprehensive, sampling a wider and more representative portion of the galaxy.

Interestingly, the researchers note that radio SETI surveys may already be less biased than often claimed, simply because of how many unintended stars fall within their observational beams.

A New Tool for Future Searches

To help other scientists apply this approach, the team developed a web-based tool called the SETI-Stellar-Bycatch-Simulator. This calculator allows users to input sky coordinates and telescope parameters to simulate which stars fall within a given field of view and where potential extraterrestrial transmitters might be located.

This tool is expected to play a key role in designing and interpreting future SETI surveys, making it easier to compare results across different telescopes and observation strategies.

The Bigger Picture in the Search for Life

This research arrives at a time when interest in technosignatures is expanding beyond radio waves. Astronomers are increasingly exploring optical, infrared, and even atmospheric technosignatures as new telescopes come online.

Despite decades of searching, the most famous potential technosignature remains the Wow! Signal, detected in 1977 by the Big Ear Radio Telescope. Although never repeated, it demonstrated how a single unexplained signal can reshape scientific curiosity and public imagination.

Studies like this one remind us that how we search is just as important as what we search for. By accounting for hidden stars, astronomers are gaining a clearer picture of the true scale of our observations—and refining our understanding of humanity’s place in the galaxy.

Why This Study Matters

By showing that SETI surveys already include far more stars than previously recognized, this research strengthens the scientific foundation of technosignature searches. It helps clarify what non-detections actually mean and provides a roadmap for making future searches more rigorous and less biased.

As technology improves and methods evolve, hidden stars may no longer remain hidden. Instead, they could become key contributors in humanity’s ongoing effort to answer one of its oldest questions: Are we alone?

Research Paper:

Simulating the Stellar Bycatch: Constraining the Prevalence of Extraterrestrial Transmitters within Radio SETI Surveys

https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.20231