How Astronomers Explained the ‘Impossible’ Merger of Two Massive Black Holes

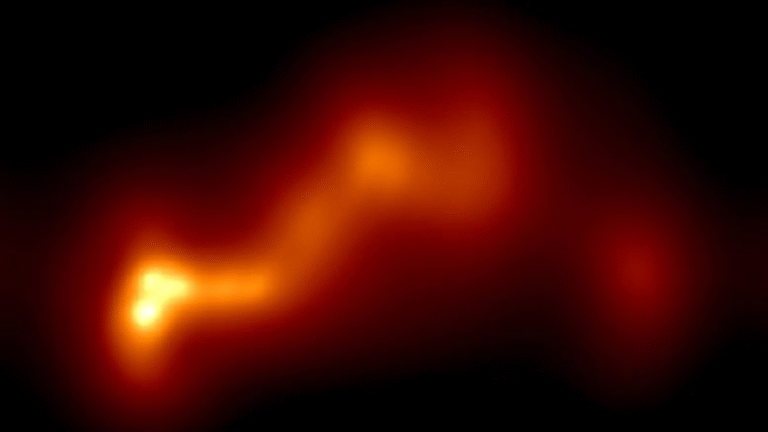

A strange gravitational-wave detection in 2023 left astronomers scratching their heads. Two unusually large black holes—far heavier and far faster-spinning than expected—had collided about 7 billion light-years from Earth. The event was labeled GW231123, and it didn’t fit neatly into any previously understood formation scenario. Black holes of this size were not supposed to exist, at least not from normal stellar evolution. Now, thanks to a new set of highly detailed simulations, researchers have finally uncovered a clear and scientifically grounded explanation for this “impossible” merger.

Understanding Why GW231123 Was So Mysterious

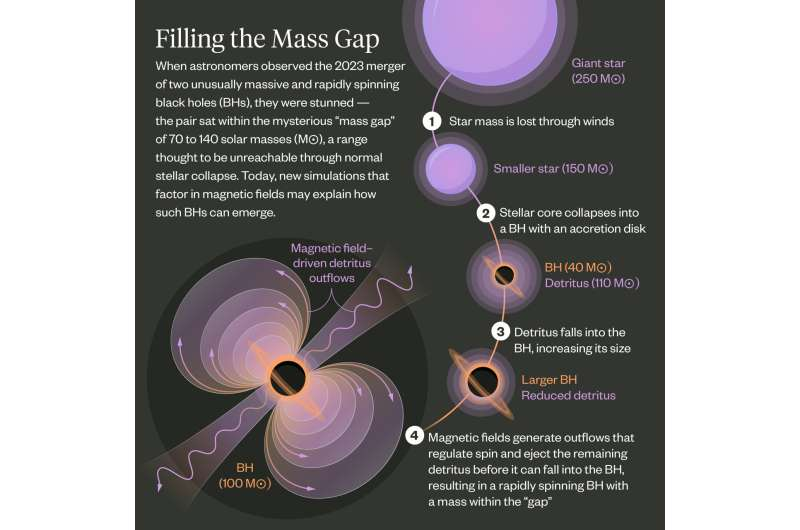

The two black holes involved in GW231123 were both exceptionally massive, falling right inside the so-called pair-instability mass gap. In standard astrophysics, stars in a specific mass range undergo pair-instability supernovae, explosions so extreme that the entire star is obliterated, leaving no black hole behind. That means black holes with masses between roughly 70 and 140 times the mass of the Sun shouldn’t form directly from collapsing stars.

Yet GW231123 featured two black holes right in that forbidden range. Even more puzzling, both were spinning incredibly fast—close to the speed at which spacetime itself is dragged around. Normally, if such massive black holes formed from earlier black hole mergers (a concept known as hierarchical merging), their spins would not align so neatly or reach such extreme values. In other words, their combination of high mass and high spin was extremely unlikely under any existing model.

The new research tackled this puzzle by following a different line of thought: what if astronomers had previously overlooked a crucial physical ingredient?

Credit: Lucy Reading-Ikkanda/Simons Foundation

The Missing Piece: Magnetic Fields

A team from the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics (CCA), led by Ore Gottlieb, created a series of end-to-end simulations tracking a massive star from its birth to its final collapse. Unlike earlier studies, their work included the full effects of magnetic fields, and this changed everything.

The first stage of the simulation followed a 250-solar-mass star through its entire life cycle. As it burned through its fuel and approached collapse, stellar winds reduced its mass to about 150 solar masses, placing it just above the range where pair-instability supernovae completely destroy the star. That made it possible—at least in principle—for the star to leave behind a very large black hole.

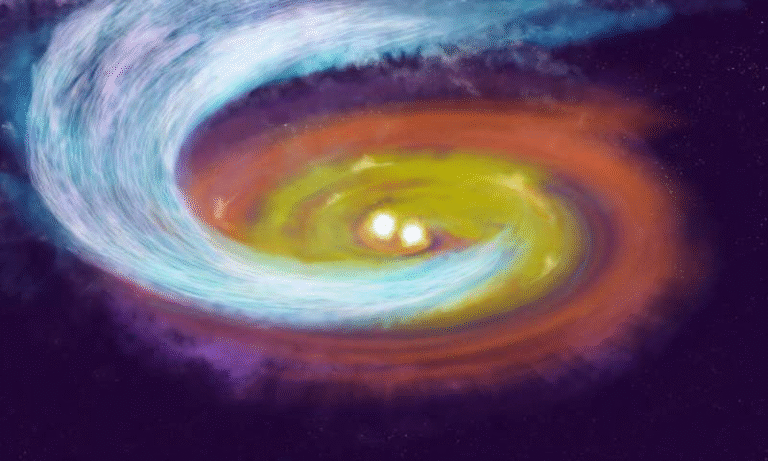

The second simulation stage examined what happens after collapse. This is where rotation and magnetic fields dramatically reshaped the outcome.

How Rotation and Magnetism Alter Black Hole Formation

If a massive star is non-rotating, the material around the newborn black hole simply falls straight in, producing a black hole whose mass closely matches the mass of the collapsing core.

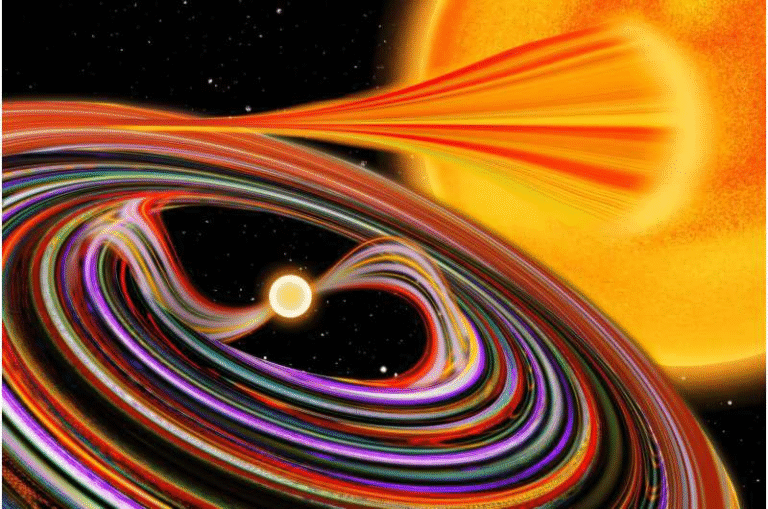

But in a rapidly rotating star, the story is different. The collapsing material forms an accretion disk around the new black hole. When this disk contains magnetic fields, those fields begin exerting pressure and launching powerful outflows—jets and winds that blast surrounding matter outward at nearly the speed of light.

This ejection significantly reduces the amount of material that ends up feeding the black hole.

The simulations revealed that:

- Stronger magnetic fields create stronger outflows

- These outflows can eject up to half of the star’s remaining mass

- The black hole ends up much lighter than the collapsing star

- The black hole’s spin depends directly on how much mass and angular momentum remain

In other words, rotation plus magnetism allow the creation of black holes inside the mass gap, something conventional models struggle to explain.

Why This Explains GW231123 Perfectly

The GW231123 merger involved two black holes with large masses and near-maximal spins. According to the new simulation results:

- Weaker magnetic fields mean less material is expelled, producing heavier black holes

- Weaker fields also allow black holes to retain high spin

- This combination—high mass and high spin—is exactly what the GW231123 system displayed

Essentially, the black holes that merged to create GW231123 likely formed from two separate massive stars with:

- Extremely fast rotation

- Relatively weak magnetic fields

- Enough mass to collapse without total destruction

- Little mass loss before collapse

The result was a pair of unusually massive, unusually fast-spinning black holes that eventually merged billions of years later.

A Possible Mass-Spin Relationship for Black Holes

One of the most interesting implications of this research is the idea that black holes may follow a mass-spin connection:

- Stronger magnetic fields → more mass ejection → lighter, slower-spinning black holes

- Weaker magnetic fields → less mass ejection → heavier, faster-spinning black holes

This suggests a natural pattern that determines the properties of black holes born from massive stars. If future gravitational-wave detections reveal similar trends, this could become a key tool for understanding black hole populations.

Additional Clues: Possible Gamma-Ray Bursts

The simulations also showed that the collapse of these massive rotating stars with magnetic fields can produce jets—and jets often create gamma-ray bursts (GRBs). If these GRBs are observed in the right place and time, they could provide independent confirmation of this formation process.

While none were detected for GW231123, the universe is enormous and conditions for observing GRBs are specific. Future detections may line up with the predictions of this model.

Why This Discovery Matters

Understanding how black holes form is fundamental to astrophysics. This research is important because it:

- Explains how mass-gap black holes can form directly from stars

- Shows that magnetic fields are not optional—they’re central to massive-star collapse

- Gives us a new framework for interpreting gravitational-wave events

- Helps refine models of stellar evolution and extreme astrophysics

- Suggests new observable signs, such as GRBs, that can verify the theory

GW231123 is now considered one of the clearest examples of how complex—and fascinating—black-hole formation can be.

Extra Background: What Is a Pair-Instability Supernova?

Because it’s central to this mystery, here’s a quick, clear explanation.

Very massive stars can reach temperatures where gamma-ray photons convert into electron-positron pairs, removing radiation pressure that supports the star’s core. The result is a runaway collapse followed by a catastrophic explosion that destroys the star entirely.

This process prevents stars in a specific mass range from forming black holes, creating the so-called mass gap.

The new research shows that rotation and magnetic fields can change how much mass is left behind, thereby allowing stars near that range to still produce black holes—even large ones.

Extra Background: Why Black-Hole Spins Matter

Black-hole spin isn’t just a small detail. High spins influence:

- The shape of spacetime around a black hole

- How matter falls into it

- How jets are launched

- How gravitational-wave signals look

A spin close to the maximum possible value means the black hole formed under highly energetic, highly asymmetric, and extremely dynamic conditions. The GW231123 black holes being such fast spinners is one of the biggest clues that pointed scientists toward a new formation scenario.