How the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope Will Use Bent Light to Reveal Complex Multi-Planet Systems

The discovery of planets beyond our solar system has always gone hand in hand with technological progress. Every major leap in telescope design, imaging sensitivity, or data processing has opened new windows into planetary systems that were previously invisible. One of the most anticipated tools in this ongoing search is NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, and scientists are already exploring what kinds of discoveries it is likely to make once it begins operations. A recent research study focuses on one particularly exciting possibility: using gravitational microlensing, or bent light, to detect and map complex planetary systems containing multiple planets.

This research, led by Vito Saggese of the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics along with collaborators from the Roman Galactic Exoplanet Survey Project Infrastructure Team, examines how effectively Roman could detect systems where a star hosts two planets. These so-called triple-lens systems—made up of one star and two orbiting planets—are rare and difficult to identify, but Roman may dramatically increase the number we know about.

What Gravitational Microlensing Really Means

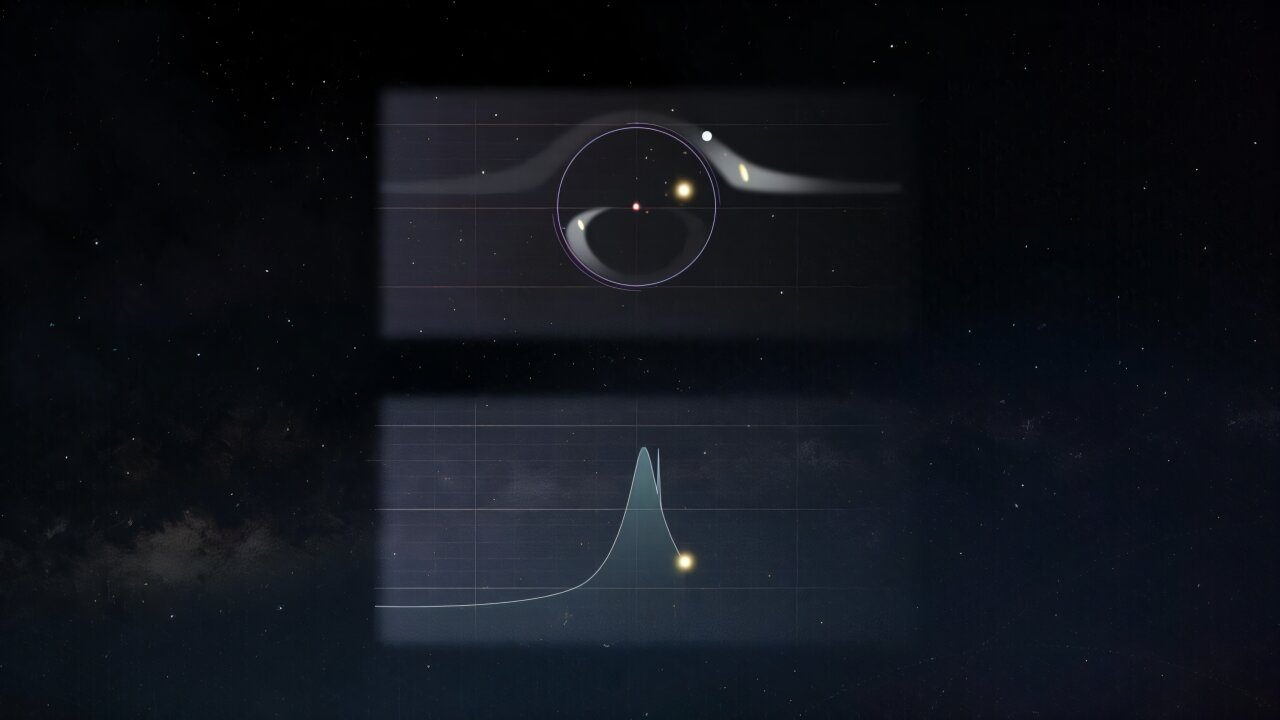

Gravitational microlensing is rooted in Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which predicts that massive objects can bend the path of light. When a foreground star passes almost directly in front of a more distant background star, the gravity of the closer star bends and magnifies the background star’s light. If the foreground star has planets, their gravity can create additional distortions in the light signal.

These distortions show up as subtle features in a light curve, a graph that tracks how the brightness of the background star changes over time. By carefully analyzing these curves, astronomers can infer the presence, mass, and position of planets orbiting the lensing star. Microlensing is especially valuable because it can detect planets that are far from their stars, including worlds located beyond the equivalent of Jupiter’s orbit, and even planets with relatively low masses.

Why Roman Is Especially Suited for Microlensing

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope has been designed with microlensing in mind. Its wide field of view and high-precision infrared detectors will allow it to monitor millions of stars simultaneously toward the dense stellar regions of the Milky Way’s bulge. This dramatically increases the chances of catching rare microlensing events.

Previous telescopes have detected multi-planet systems using microlensing, but only 11 confirmed cases exist so far. These detections required careful follow-up and were often at the limits of what older instruments could manage. Roman’s improved sensitivity and continuous monitoring capabilities make it uniquely positioned to expand this small sample.

Simulating Millions of Planetary Systems

To estimate Roman’s capabilities, the researchers ran an extensive simulation. They created 1.3 million synthetic light curves, each representing a hypothetical triple-lens system with one star and two planets. These simulations intentionally included noise and observational imperfections to closely mimic real astronomical data.

The goal was to test how often Roman’s detection infrastructure could correctly identify both planets in a system rather than mistaking the signal for a simpler configuration. Overall, the results were encouraging: the system successfully identified 66.3% of all triple-lens configurations as multi-planet systems.

Planet Positions Make a Big Difference

One of the strongest factors influencing detection success is where the planets are located relative to their host star. The researchers divided planetary configurations into three main categories: close, wide, and resonant.

Resonant configurations occur when planets are located near the Einstein ring, the region where light bending effects are strongest during a microlensing event. These turned out to be the easiest systems to detect, with detection efficiency jumping to an impressive 93%.

At the other extreme are systems where both planets are classified as wide, meaning they orbit far from their star. In these cases, detection efficiency dropped to around 55%. While still significant, this is well below the resonant case. Systems with close-in planets fell somewhere in between, reflecting the complex geometry of how gravitational signals overlap during lensing events.

Planetary Mass Also Matters

The mass of the planets plays an equally important role. When both planets in a system are massive—comparable to Jupiter or larger—the detection rate climbs to around 90%. Massive planets create stronger gravitational signatures, making them easier to distinguish in the light curve.

Smaller planets, however, can be much harder to spot. Their signals are more easily drowned out by noise, especially when both planets are low in mass. Mixed systems, where one planet is massive and the other is small, produced mixed results. In some cases, the gravitational influence of the larger planet overshadowed the smaller one, making the system appear simpler than it really was.

What Roman Is Expected to Discover

By combining all these results, the researchers estimated how many multi-planet microlensing events Roman is likely to detect over its mission lifetime. Their calculations suggest Roman could observe 64 triple-lens events, representing about 4.5% of all microlensing exoplanet detections the telescope is expected to make.

This may sound like a modest fraction, but the impact is substantial. Detecting 64 such systems would increase the total number of known multi-planet microlensing systems by a factor of six. That alone would provide astronomers with a much richer dataset for studying planetary formation and orbital dynamics in environments very different from our own solar neighborhood.

Why Multi-Planet Microlensing Systems Are Important

Most exoplanet detection methods, such as the transit method, are biased toward close-in planets that orbit near their stars. Microlensing, by contrast, is sensitive to planets located at wider separations and even to planets orbiting faint or distant stars.

Multi-planet systems detected through microlensing can reveal how planets form and evolve in regions of space that are otherwise difficult to study. They also help scientists test whether planetary systems like our own are common or unusual within the Milky Way.

A Broader Look at Gravitational Microlensing

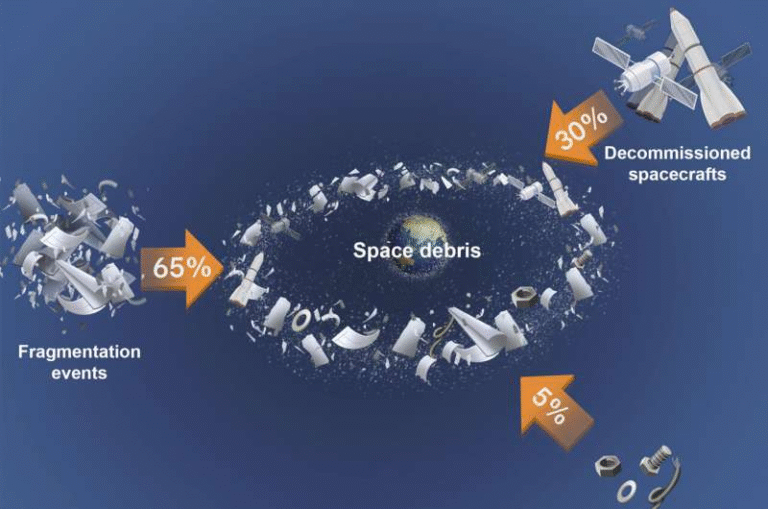

Beyond detecting planets, microlensing has been used to study stellar populations, measure stellar masses, and even probe dark objects like isolated black holes. Roman’s microlensing survey is expected to detect thousands of exoplanets overall, including free-floating planets that are not bound to any star.

The study by Saggese and colleagues shows that Roman will not only expand the number of known exoplanets but also deepen our understanding of planetary system architectures, especially those involving multiple worlds interacting gravitationally.

A Clear Example of Technology Driving Discovery

Ultimately, this research highlights a familiar theme in astronomy: new technology enables new science. The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will allow astronomers to explore planetary systems that have remained hidden until now, using the subtle bending of light itself as a detection tool. Even if some systems only offer incremental insights, the overall leap in capability promises a far clearer picture of how planetary systems are built across our galaxy.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.05182