How Tracking a Pulsar’s Radio Twinkle Helps Scientists Sharpen Cosmic Timekeeping

For decades, pulsars have been treated as some of the most reliable natural clocks in the universe. These dense, rapidly spinning remnants of massive stars emit radio pulses with astonishing regularity, allowing astronomers to measure time across vast cosmic distances with extreme precision. But new research shows that even these cosmic clocks are subtly influenced by their journey through space. A recent study led by the SETI Institute reveals that slow changes in a pulsar’s radio “twinkle” can nudge pulse arrival times by mere billionths of a second, a tiny effect with big implications for precision astronomy.

The research focuses on a well-known and particularly bright pulsar called PSR J0332+5434, also known as B0329+54. Over a period of 10 months, scientists carefully monitored this pulsar using the Allen Telescope Array (ATA) at the Hat Creek Radio Observatory in Northern California. Their goal was to understand how the pulsar’s radio signals are distorted as they pass through the gas and electrons that fill the space between stars, a region known as the interstellar medium.

Why Pulsar Timing Matters

Pulsars are formed when massive stars explode as supernovae and collapse into neutron stars, packing more mass than the Sun into a sphere roughly the size of a city. As they spin, beams of radio waves sweep across space like lighthouse beams. When one of these beams crosses Earth, radio telescopes detect it as a pulse. For many pulsars, these pulses arrive with incredible regularity, making them ideal tools for experiments that demand extreme timing accuracy.

One of the most important applications of pulsar timing is the search for low-frequency gravitational waves. Networks of precisely timed pulsars, known as pulsar timing arrays, are used to detect subtle ripples in spacetime caused by events such as the mergers of supermassive black holes. To succeed, scientists must measure pulse arrival times with accuracies down to tens of nanoseconds.

However, pulsar signals do not travel through empty space. Along the way, they pass through clouds of ionized gas containing free electrons. These electrons scatter the radio waves, spreading them out and slightly delaying their arrival at Earth. Understanding and correcting for these delays is essential if pulsars are to remain reliable cosmic clocks.

The Science of Radio Scintillation

The effect at the heart of this study is known as radio scintillation. It is closely related to the twinkling of stars seen with the naked eye, which is caused by turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere. In space, a similar phenomenon occurs when radio waves pass through irregularities in the interstellar medium.

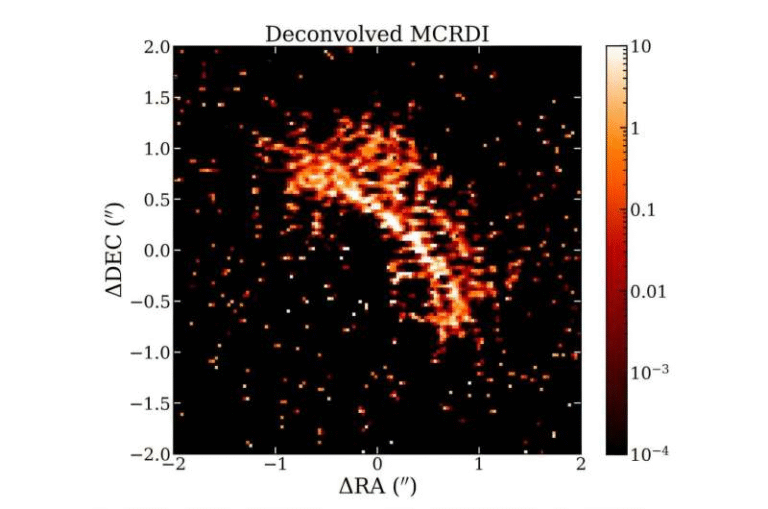

As pulsar radio waves travel through clouds of electrons, they form patterns of bright and dim patches across different radio frequencies. These patterns are not fixed. They evolve over time as the pulsar moves, the interstellar gas shifts, and Earth changes position in its orbit. This evolving “twinkle” directly affects how much the pulsar signal is delayed.

The key insight of the new research is that the strength of scintillation is closely tied to timing delays. When scintillation changes, the arrival time of pulses changes too, even if only by billionths of a second.

A Long-Term Monitoring Effort

To study this effect in detail, the research team used the Allen Telescope Array to observe PSR J0332+5434 across a wide range of radio frequencies, from 900 to 1,956 megahertz. The ATA is particularly well suited for this kind of work because it combines wide bandwidth coverage with the ability to carry out frequent, short observation sessions over long periods.

Over roughly 300 days, the team measured the pulsar’s scintillation bandwidth, which describes the size of the bright patches in the twinkling pattern. These measurements were taken almost daily, providing an unusually detailed view of how scintillation evolves over time.

What the scientists found was striking. The amount of scintillation did not remain constant but changed significantly on timescales ranging from days to months. On top of these shorter fluctuations, the data revealed a broader, long-term variation lasting around 200 days. This slow evolution suggests that large-scale structures in the interstellar medium are influencing the pulsar’s signal over extended periods.

Turning Twinkles Into Timing Corrections

One of the major achievements of the study was translating changes in scintillation into quantitative timing delays. These delays were often on the order of tens of nanoseconds, small enough to be invisible in most astronomical measurements but critically important for high-precision pulsar timing experiments.

The researchers also developed a new, more robust method for estimating how scintillation changes with radio frequency. Thanks to the ATA’s wide frequency coverage, they were able to measure how scintillation increases at higher frequencies and confirm that the behavior matches theoretical expectations for turbulence in the interstellar medium.

This improved understanding allows scientists to better correct for timing distortions caused by interstellar scattering. In practical terms, it means pulsar timing arrays can become more accurate, improving their sensitivity to gravitational waves and other subtle cosmic signals.

Implications for SETI and Radio Astronomy

The findings have relevance beyond pulsar timing and gravitational wave research. All radio signals traveling through the interstellar medium experience scintillation, not just those from pulsars. This includes any potential technosignatures, or radio signals from advanced extraterrestrial civilizations, that SETI researchers hope to detect.

Because interstellar scintillation affects distant cosmic signals but not most human-made radio interference, understanding these patterns helps scientists distinguish between natural or extraterrestrial signals and local noise. In this way, studying pulsar twinkling contributes directly to the broader goals of SETI.

The study also highlights the value of instruments like the Allen Telescope Array, which are capable of long-term, dedicated monitoring projects that might be difficult to carry out on more oversubscribed telescopes.

What This Tells Us About the Interstellar Medium

Beyond its practical applications, the research provides a window into the structure of the space between stars. The observed scintillation variations reflect turbulence and density changes in the interstellar medium, offering clues about how gas and electrons are distributed across our region of the galaxy.

By carefully tracking a single, nearby pulsar over many months, scientists can probe these otherwise invisible structures and refine models of how radio waves propagate through space. This kind of knowledge benefits not only pulsar studies but radio astronomy as a whole.

A Small Effect With Big Consequences

At first glance, a timing shift of a few billionths of a second may seem insignificant. But in the world of precision astrophysics, these tiny delays matter. As pulsar timing experiments push toward ever greater accuracy, effects like slow changes in scintillation can no longer be ignored.

This study shows that with careful monitoring, wide frequency coverage, and long-term commitment, scientists can measure and correct for these subtle influences. The result is a clearer, more stable cosmic clock and a deeper understanding of the space between the stars.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ae0fff