Hubble Telescope Captures a Rare and Violent Collision in the Fomalhaut Planetary System

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has done something astronomers have long hoped for but never actually witnessed beyond our own solar system: it has captured the direct aftermath of massive space rocks colliding inside a nearby planetary system. This extraordinary observation offers scientists a rare, real-time look at how planetary systems evolve and how planets themselves may form from violent beginnings.

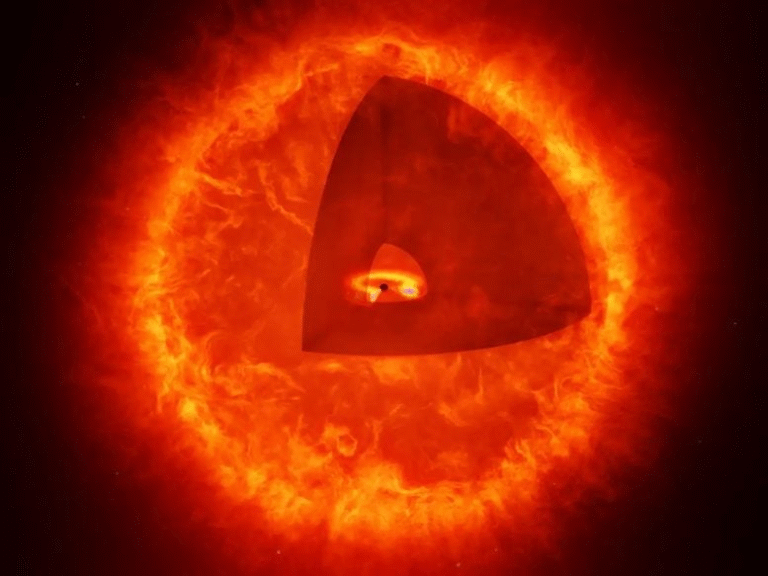

The event took place around Fomalhaut, a bright star located about 25 light-years from Earth in the constellation Piscis Austrinus. Fomalhaut has been studied for decades because it is surrounded by an enormous and complex disk of dust and debris, making it one of the most intriguing nearby stellar systems for understanding planetary formation.

A Discovery That Challenged Expectations

When astronomers first detected a bright point of light near Fomalhaut years ago, they assumed it was an exoplanet reflecting starlight. This object, known as Fomalhaut b, appeared stable and planet-like in early observations. However, something puzzling happened over time. The supposed planet slowly faded and eventually disappeared entirely from Hubble’s images.

Then, in a surprising twist, a new bright object appeared in a slightly different location within the same dust belt. This sudden change forced scientists to rethink everything they believed they were seeing. Rather than planets, these bright points turned out to be expanding clouds of debris, created by violent collisions between large rocky bodies called planetesimals.

Two Collisions in Just 20 Years

What makes this discovery truly remarkable is that astronomers now believe two separate collisions occurred in the Fomalhaut system within the last two decades. These debris clouds are now classified as Fomalhaut cs1 and Fomalhaut cs2, with “cs” standing for circumstellar source.

- Fomalhaut cs1, previously known as Fomalhaut b, was imaged in 2012 and has since faded away as its dust dispersed.

- Fomalhaut cs2, discovered in 2023, appears strikingly similar to cs1 in brightness, size, and location within the debris disk.

According to theoretical models, collisions between planetesimals of this scale should happen only once every 100,000 years or more. Yet astronomers witnessed two such events in just 20 years, suggesting the Fomalhaut system is far more dynamically active than expected.

Why These Collisions Matter

Planetesimals are the building blocks of planets. In the early stages of a planetary system, countless collisions occur as small rocky bodies smash together, gradually forming larger worlds. However, directly observing such events has always been nearly impossible due to vast distances and limited resolution.

This is the first confirmed observation of large planetesimal collisions outside our solar system, giving scientists invaluable data. By studying how the debris clouds expand, fade, and respond to stellar radiation, researchers can better understand the physical structure, composition, and behavior of these primordial building blocks.

These observations also have implications closer to home. Understanding how rocky bodies break apart during collisions informs models used in planetary defense, including missions like NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), which focuses on altering asteroid trajectories.

A Case of Mistaken Identity in Exoplanet Hunting

One of the most important lessons from this discovery is how easily debris clouds can masquerade as planets. Both cs1 and cs2 reflected starlight in a way that closely mimicked the appearance of a real exoplanet. For years, Fomalhaut b was considered a strong planetary candidate.

This misidentification serves as a cautionary reminder for future missions that aim to directly image planets around nearby stars. As next-generation observatories like the Giant Magellan Telescope and other large ground-based and space telescopes come online, astronomers will need to carefully distinguish between true planets and temporary dust clouds created by cosmic collisions.

Why Fomalhaut Is Such a Special Target

Fomalhaut is more massive and more luminous than our Sun, and its debris disk is one of the largest and brightest ever observed. This massive dust belt makes it easier for astronomers to detect transient events like collisions, which might go unnoticed in less dusty systems.

The system has been monitored by Hubble for over 20 years, providing a rare long-term dataset. Without this extended observation history, scientists may never have realized that these bright objects were fleeting debris clouds rather than permanent planets.

The Role of Hubble and the Transition to JWST

Although Hubble made this groundbreaking discovery, the telescope is now showing its age. Its instruments are no longer capable of collecting the detailed spectral data needed to fully analyze the dust clouds.

Fortunately, astronomers have secured observation time with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Using JWST’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), scientists will be able to study Fomalhaut cs2 in far greater detail. This includes analyzing the color, size, and composition of dust grains, as well as searching for signs of water ice or other volatile materials.

These observations could reveal whether the colliding planetesimals contained water-rich material, offering insights into how water might be delivered to forming planets elsewhere in the universe.

What These Collisions Tell Us About Planet Formation

Planet formation is not a gentle process. It is chaotic, violent, and shaped by countless impacts. The Fomalhaut collisions provide a rare snapshot of this process in action, rather than relying solely on simulations and indirect evidence.

Seeing two collisions in such a short span of time suggests that some planetary systems may experience extended periods of intense bombardment, far beyond what current models predict. This could reshape how scientists think about the early evolution of planetary systems, including our own.

Looking Ahead

Astronomers will continue monitoring the Fomalhaut system to track how cs2 evolves over time. There is also the possibility that more collisions could be detected in the future, turning this system into a natural laboratory for studying planetary construction in real time.

What began as a confusing disappearance of a suspected planet has turned into one of the most important observational breakthroughs in modern astronomy. By catching these rare cosmic smashups on camera, Hubble has once again demonstrated its lasting scientific legacy, even as newer telescopes prepare to take over the search for answers.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adu6266