Icarus Returns to Space With a New Satellite Constellation for Global Wildlife Tracking

The Icarus wildlife-tracking project is preparing for a major comeback after a three-year pause, and this time it’s returning with upgraded technology, new partners, and a long-term plan to build a full satellite constellation in orbit. A new SpaceX launch scheduled for 11 November 2025 will carry the first next-generation Icarus receiver into space, marking the beginning of a new phase in global animal-movement research.

This first receiver will be hosted on the GENA-OT CubeSat, a satellite platform developed by OroraTech. After reaching orbit, the system will undergo about three months of testing. Once operational, the receiver will connect with miniature sensors attached to animals around the world, providing researchers with continuous data about movement, behaviour, health, and environmental conditions. Unlike earlier versions of Icarus, this new setup will finally allow full global coverage, making it possible to follow the lives and migrations of species ranging from migratory birds and bats to sea turtles and large mammals.

The 2025 launch is just the first step. A second Icarus receiver is already built and scheduled for another SpaceX mission in 2026, jointly operated by the Max Planck Society and the space company Talos. Additional satellites are already in planning. By mid-2027, the goal is to operate a constellation of six Icarus receivers, which will significantly increase data frequency, speed, and coverage.

How Icarus Began and Why It Paused

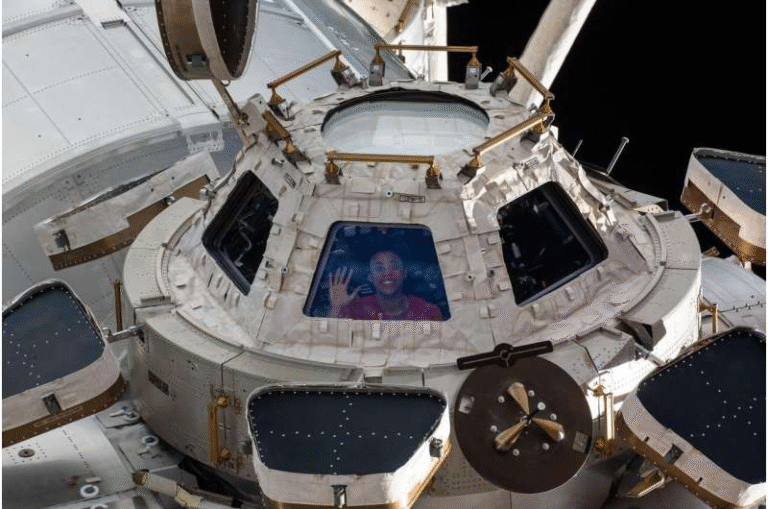

Icarus originally launched in 2020 as an experiment aboard the International Space Station (ISS). An antenna mounted on the ISS collected signals from lightweight tracking tags attached to animals. Researchers gained new insights into migration routes, breeding patterns, and survival strategies, creating one of the largest global databases of animal movement ever recorded.

However, in 2022, the war in Ukraine abruptly ended the collaboration between the original project partners, including the Russian space agency. Because key components of the Icarus system relied on this cooperation, operations had to be paused. Instead of abandoning the project, the team took this break as an opportunity to re-engineer the system from the ground up.

This redesign was carried out with Talos, a Munich-based NewSpace company. Their work led to a major leap in miniaturization: the new receiver fits into a ten-centimeter CubeSat payload, uses only one-tenth the energy, reads four times as many sensors, and supports faster data downloads and remote software updates. All of this was successfully tested during an experimental orbital flight in 2023. What once required a massive, power-hungry antenna on the ISS now fits into the palm of a hand.

The Launch Partners and Their Roles

The new space mission is being carried out through a collaboration between the Icarus project and the Seranis research mission at the University of the Bundeswehr Munich. Seranis operates a fleet of small satellites designed to serve as a laboratory in orbit. The GENA-OT CubeSat, built by OroraTech, is one of these platforms and will host the first new Icarus receiver.

After the test phase in orbit at around 500 kilometers altitude, the receiver will begin two-way communication with the animal sensors. Not only will the miniature tags send precise GPS and environmental data to the satellite, but researchers will also be able to remotely reprogram the sensors, which avoids the need to physically retrieve them from animals.

The Vision for ICARUS 2.0

The upcoming constellation is being referred to as ICARUS 2.0, and it represents a significant evolution of the project. With a second receiver launching in 2026 and four more planned, the system aims to create continuous, near-real-time monitoring of global animal movement by 2027.

This improved coverage means researchers will be able to track animal well-being with much finer detail, detect biological threats such as disease outbreaks earlier, and better understand how wildlife responds to ecological disruptions like climate change or habitat shifts. The expansion will make Icarus one of the most powerful biodiversity-monitoring systems on the planet.

To support this, Talos is developing a new generation of Icarus tags. These tags will be among the lightest and most energy-efficient sensors available. In addition to GPS location, they will measure environmental variables such as temperature, humidity, air pressure, and acceleration, giving researchers a detailed picture of both animal health and their surroundings. On-board data processing will help filter and structure information before transmission, conserving energy and improving data quality.

A Tool for Conservation and Global Biodiversity Research

Icarus 2.0 comes at a moment when both biodiversity loss and climate pressures are accelerating. To strengthen the project’s scientific reach, Icarus is now embedded within the Animal Movement Biodiversity Observation Network (Move BON). This integration ensures that the data collected by Icarus can be translated into indicators used in global biodiversity monitoring systems.

These indicators can identify environmental degradation, track migratory connectivity across continents, measure species resilience, and guide decisions in conservation policy. By tying animal movement directly to ecological health, Icarus offers a powerful way to understand how Earth’s living systems are changing.

The information could also help predict the spread of zoonotic diseases, track endangered species under pressure from environmental change, and support national and international conservation planning.

Understanding CubeSat Technology

Since CubeSats are central to ICARUS 2.0, it’s worth learning how they work. CubeSats are standardized mini-satellites based on units of 10 × 10 × 10 cm, called “1U.” A satellite might be 1U, 3U, 6U, or even 12U depending on its mission. They are far lighter and cheaper than traditional satellites, which makes it possible for scientific missions like Icarus to scale up quickly.

CubeSats can carry scientific instruments, Earth-observation sensors, communication systems, and more. Their compact size means they can piggyback on larger rocket launches—such as SpaceX’s rideshare missions—dramatically lowering costs. For wildlife tracking, this flexibility is exactly what allows Icarus to plan a multi-satellite constellation without the massive expense of older systems.

How Animal Tracking Sensors Work

Modern wildlife tags pack surprising technology into tiny devices weighing just a few grams. A typical Icarus tag includes:

- GPS modules for location

- Accelerometers for behaviour and movement

- Environmental sensors (temperature, humidity, pressure)

- Solar cells or long-life batteries

- A radio transmitter to send data to satellites

- On-board computing for data filtering

This combination allows scientists to understand not just where an animal moves, but how it behaves hour by hour, how it interacts with weather patterns, and how it adapts to changes in its habitat. These tags can track migration routes, detect unusual movement patterns that might signal illness, and monitor population shifts in response to climate change.

Why This Relaunch Matters

The transformation from the original ISS-based system to the new CubeSat constellation is a major step toward building a planet-wide wildlife observatory. More frequent data, global coverage, and the ability to update sensors remotely will give scientists tools they simply didn’t have before.

As the world faces challenges such as climate change, habitat loss, and biodiversity decline, understanding how animals move and adapt is essential. Projects like Icarus help connect individual animal journeys to the health of entire ecosystems, revealing patterns that otherwise remain invisible.

Research Reference: Max Planck Society