James Webb Space Telescope Reveals Unprecedented Details Inside the Sagittarius B2 Star-Forming Giant

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has delivered one of its most striking and scientifically valuable views yet, turning its powerful Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) toward the Sagittarius B2 molecular cloud, the most massive and active star-forming region in the Milky Way. The image, released on September 24, 2025, offers an extraordinarily detailed look at glowing dust, dense gas, and newborn massive stars hidden deep within one of the galaxy’s most extreme environments.

Sagittarius B2, often shortened to Sgr B2, sits only a few hundred light-years from the Milky Way’s central supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*. Despite its relatively compact size compared to the broader Galactic Center region, Sgr B2 plays an outsized role in stellar production. Astronomers estimate that while it contains only about 10% of the gas found in the Galactic Center, it is responsible for nearly 50% of the stars forming there. Understanding why this single cloud is so extraordinarily productive has become a major focus of modern astrophysics, and Webb’s new observations are providing critical clues.

What Makes the New Webb Image So Important

The latest image was captured using MIRI, an instrument designed to observe the universe in mid-infrared wavelengths. This part of the electromagnetic spectrum is particularly valuable for studying star formation because it can penetrate thick clouds of dust that block visible and near-infrared light. In regions like Sagittarius B2, where dense dust cocoons surround newborn stars, mid-infrared observations are often the only way to see what is truly happening inside.

The image reveals glowing cosmic dust heated by extremely young, massive stars, many of which are still deeply embedded in their natal material. Bright points of light mark the most energetic stars capable of shining through the dust, while vast clouds of warm gas and dust appear as luminous, textured structures spread across the scene. The result is a colorful but scientifically precise map of one of the galaxy’s most intense stellar nurseries.

MIRI is not just a camera. It also includes a spectrograph, which allows astronomers to break incoming light into its component wavelengths. This capability makes it possible to identify chemical signatures, measure temperatures, and estimate the masses and ages of stars forming within the cloud. Follow-up studies using this spectral data are expected to reveal how stars in Sagittarius B2 grow and evolve under extreme conditions.

Sagittarius B2: A Stellar Factory Near the Galactic Core

Sagittarius B2 is widely regarded as the largest molecular cloud complex in the Milky Way. With a mass estimated at around three million times that of the Sun, it dwarfs most star-forming regions found in the galaxy’s spiral arms. Its density is also remarkable, with hydrogen concentrations tens of times higher than typical molecular clouds.

Its location near the Galactic Center adds another layer of complexity. This region of the galaxy is turbulent, crowded, and influenced by strong gravitational forces, magnetic fields, and shock waves. These harsh conditions would seem, at first glance, unfavorable for star formation. Yet Sagittarius B2 defies expectations by forming stars at an exceptionally high rate, particularly massive stars, which play a key role in shaping galaxies through radiation, stellar winds, and supernova explosions.

One of the biggest mysteries astronomers hope to solve is why Sgr B2 is so efficient. Is it being compressed by gravitational tides from the Galactic Center? Are cloud-cloud collisions triggering bursts of star formation? Or does its chemical richness give it an advantage? Webb’s observations are designed to help answer these questions.

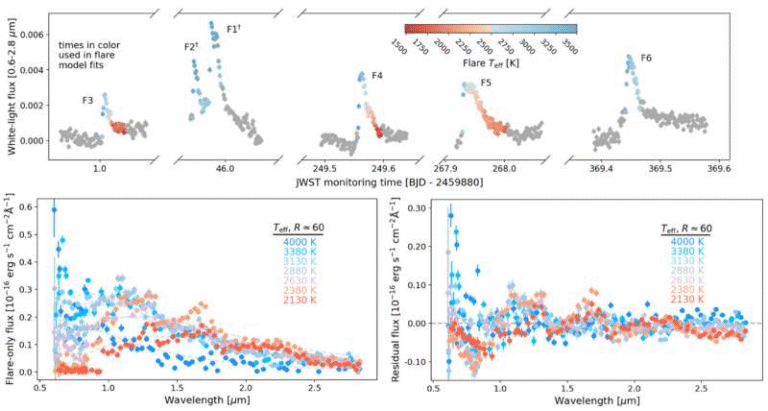

What the Image Reveals About Star Formation

The new MIRI image shows that Sagittarius B2 is far from uniform. Some regions shine brightly, filled with heated dust and active star formation, while others appear surprisingly dark, even at mid-infrared wavelengths. These darker zones are believed to contain extremely dense and cold material, possibly hiding stars that are so young they have not yet begun heating their surroundings.

Particularly notable are areas known as Sgr B2 North and Sgr B2 Main, which are among the richest chemical environments ever observed in space. These regions are famous for containing a wide variety of complex organic molecules, making them important laboratories for studying interstellar chemistry and the building blocks of life.

By comparing MIRI data with observations from Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and older radio telescope studies, astronomers can build a layered understanding of how stars form at different stages. Near-infrared images show more exposed stars, while mid-infrared images highlight dust heating and deeply embedded stellar embryos.

Why Mid-Infrared Observations Matter

Mid-infrared astronomy plays a crucial role in modern astrophysics because it bridges the gap between visible light and radio waves. Dust grains heated by stars emit strongly in this range, making instruments like MIRI uniquely suited to tracing energy flow in star-forming regions.

In Sagittarius B2, this means astronomers can directly observe how young stars affect their environment, how radiation escapes dense clouds, and how feedback from massive stars might regulate future star formation. These insights are not limited to our galaxy. Understanding extreme regions like Sgr B2 helps scientists interpret starburst regions in other galaxies, including those seen in the early universe.

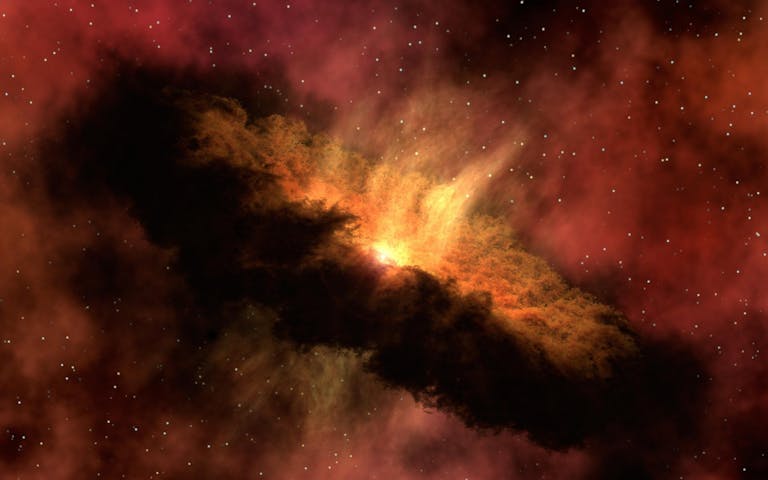

Additional Context: Molecular Clouds and Galactic Evolution

Molecular clouds like Sagittarius B2 are the birthplaces of stars, composed primarily of hydrogen molecules along with dust and trace chemicals. Their internal balance between gravity, turbulence, and radiation determines whether they collapse to form stars or remain dormant.

Massive stars formed in clouds like Sgr B2 have short but influential lives. They enrich the surrounding medium with heavy elements, sculpt nearby gas through intense radiation, and eventually explode as supernovae. These processes help drive galactic evolution, influencing everything from star formation rates to the structure of spiral arms.

Sagittarius B2 stands out because it combines enormous mass, extreme density, and proximity to the Galactic Center, making it one of the most valuable natural laboratories for studying how stars form under conditions very different from those near the Sun.

Looking Ahead

The newly released image is only the beginning. Astronomers plan to use Webb’s spectroscopic data to measure stellar ages, chemical compositions, and physical conditions across Sagittarius B2 in unprecedented detail. These studies are expected to refine models of star formation, particularly in environments shaped by strong gravity and high turbulence.

By revealing what was once hidden behind thick curtains of dust, the James Webb Space Telescope is not just providing beautiful images. It is offering a deeper understanding of how stars are born, how galaxies evolve, and why certain regions of the universe are far more productive than others.

Research paper reference: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.11771