JWST’s Deep Search for an Exomoon Around Kepler-167e Likely Found a Starspot Instead

The idea of finding a moon orbiting a planet outside our solar system has fascinated astronomers for decades. When the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) launched in late 2021, one of its most anticipated capabilities was the possibility of detecting these elusive worlds, known as exomoons. After several years of operation and multiple attempts, JWST has yet to confirm a single exomoon. A new study led by David Kipping of Columbia University helps explain why this challenge is far tougher than many originally hoped.

The research focuses on Kepler-167e, a Jupiter-like exoplanet that initially appeared to be one of the best possible candidates for hosting a detectable moon. Using an enormous amount of JWST observing time, the team searched carefully for signs of an exomoon. What they found, however, is a reminder of how subtle and complex astronomical data can be. The most likely explanation for the signal they detected is not a moon at all, but a starspot on the host star.

Why Finding Exomoons Is So Difficult

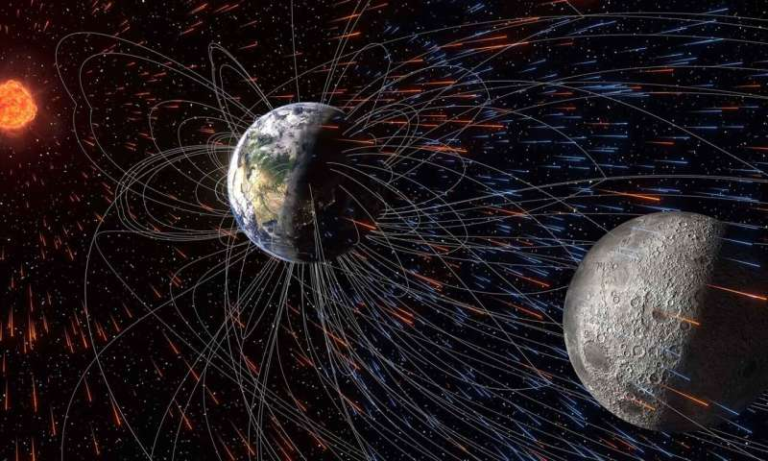

Exomoons are small compared to planets, and planets themselves are tiny compared to stars. When a planet passes in front of its star, it creates a small dip in brightness called a transit. A moon orbiting that planet would create an even smaller, secondary dip, often buried deep within noise from instruments and natural stellar variability.

JWST is the most powerful space telescope ever built, but even it struggles with this task. The telescope must distinguish between a true astrophysical signal and subtle effects caused by detector systematics, thermal changes, or stellar surface features. This difficulty is the backdrop for the new study, which shows just how close astronomers can come to finding a moon, and how easily that signal can still be explained by something else.

Kepler-167e: A Near Twin of Jupiter

Kepler-167e stands out among known exoplanets. It is about 0.91 times the mass of Jupiter and orbits its star at roughly 1.88 astronomical units, placing it between the orbital distances of Mars and Jupiter in our own solar system. The star it orbits lies about 1,119 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus.

This planet is often described as one of the closest Jupiter analogs ever discovered. That matters because Jupiter hosts more than 70 known moons, including Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system. If any exoplanet were likely to host a detectable moon, Kepler-167e seemed like an excellent bet.

The system also contains three inner super-Earths, which complicate the analysis. Their gravitational and photometric effects had to be carefully modeled and removed from the data before any potential moon signal could be examined.

An Extraordinary JWST Observation Campaign

To search for a moon, Kipping and his colleagues were awarded 60 hours of JWST observing time using the NIRSpec instrument. This is an extraordinary amount of time for a single target, highlighting how important and competitive exomoon science has become.

The observations were divided into six separate 10-hour segments, each separated by short breaks. Over these long sessions, the researchers noticed something concerning. The light curves showed a gradual decrease in brightness over each 10-hour window, an effect attributed to detector behavior rather than astrophysical changes.

Unfortunately, this detector drift occurred on nearly the same timescale as the signal expected from an exomoon transit. That overlap made it extremely difficult to tell whether any dip in brightness was real or artificial.

Multiple Pipelines and Competing Models

To minimize bias, the team processed the data through three independent pipelines. One was custom-built specifically for this dataset, while the other two, ExoTiC-JEDI and katahdin, are well-established tools in exoplanet research.

Each pipeline’s output was then tested against four different models, ranging from simple mathematical fits to more sophisticated approaches using Gaussian processes with a Matérn-3/2 kernel. These models are designed to handle correlated noise and complex systematics, but they also introduce flexibility that can sometimes fit multiple physical scenarios equally well.

Out of 12 total pipeline-model combinations, seven showed evidence consistent with an exomoon. At first glance, this seemed promising. But astronomy demands extreme caution, especially when extraordinary claims are involved.

Exomoon or Starspot?

The problem lies in interpretation. The signal that matched an exomoon model could also be explained by a syzygy-like event, a configuration where the star, planet, and an apparent feature align in a way that mimics a moon transit. In this case, the alignment was most likely caused by the planet crossing over a large starspot.

Although Kepler-167 is considered a relatively quiescent star, earlier observations from the Kepler and Spitzer space telescopes showed that it can produce starspots large enough to cause noticeable dips in brightness. These spots can easily masquerade as a moon signal if the timing is just right.

Another red flag came from the inferred size of the hypothetical moon. To explain the observed dip, the moon would need to be about 30 percent larger than formation models predict is realistic for a planet like Kepler-167e. That discrepancy further weakened the exomoon interpretation.

Taken together, the evidence strongly favored the starspot explanation over the existence of a moon.

A Valuable Negative Result

While it may seem disappointing, the researchers emphasized that this outcome is still scientifically valuable. Ruling out false positives is just as important as making discoveries. The study provides a clear example of how instrumental effects, stellar activity, and data modeling choices can all conspire to produce convincing but misleading signals.

The team concluded that, despite the massive effort and observing time invested, they could not confidently claim the detection of an exomoon. This honesty reflects the rigorous standards required in modern astrophysics.

What This Means for the Search for Exomoons

So far, JWST has identified two other potential exomoon candidates, but neither has been confirmed. One involves WASP-39b, a hot Saturn-like planet with unusual sodium and sulfur dioxide variability that could be explained by a volcanic moon. Another involves W1935, a brown dwarf with unexplained methane emissions that might originate from an unseen companion. In both cases, the evidence remains indirect.

The Kepler-167e study shows that even under ideal conditions, exomoon detection pushes current technology to its limits. It also highlights the need for repeat observations. A second transit observation would allow astronomers to see whether the same signal appears again in the same way, something a starspot is unlikely to replicate perfectly.

Looking Ahead to 2027 and Beyond

The authors have proposed another JWST observation during Kepler-167e’s next transit in October 2027. Whether JWST will allocate another large block of time remains uncertain, given the telescope’s heavy demand.

Even if this specific follow-up does not happen, several dedicated exomoon search programs are already underway or planned for upcoming JWST cycles. As data analysis techniques improve and more transits are observed, the odds of a genuine detection continue to rise.

For now, the hunt for exomoons remains open. This study does not close the door on their existence. Instead, it provides a clear roadmap for how careful astronomers must be when claiming one of the most exciting discoveries in planetary science.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.15317