Life Might Be Best Understood as Matter That Uses Meaningful Information to Stay Alive

What exactly is life, when you strip it down to its most fundamental components? Is it just chemistry behaving in complicated ways, or is there something deeper going on beneath the molecules? A new scientific study suggests that life may be best understood not simply as matter or energy, but as matter that processes meaningful information in order to survive.

A recent paper by physicist Stuart Bartlett of Caltech, along with several co-authors from fields ranging from physics to astronomy and astrobiology, proposes a fresh framework for defining life. Published in the journal PRX Life, the study argues that information—specifically semantic information—plays a central and defining role in what makes something alive.

This perspective doesn’t replace biology or chemistry. Instead, it adds another layer to how scientists think about living systems, especially when considering life beyond Earth.

Life as an Information-Processing System

Traditional definitions of life usually focus on chemistry, metabolism, or thermodynamics. Living things consume energy, maintain order, and reproduce. While all of that is true, Bartlett and his colleagues argue that these definitions miss something essential.

According to the new framework, life is characterized by its ability to process information that has meaning for its survival. This type of information is called Semantic Information, or SI.

Semantic Information is not just raw data. It is information that directly affects whether an organism continues to exist. For example, recognizing that a certain chemical signal means “toxin” or that a temperature drop threatens survival are forms of semantic information. Acting on this information helps the organism remain viable.

By contrast, Syntactic Information refers to raw, meaningless data. It may exist in the environment, but if it has no impact on survival, living systems can safely ignore it.

Viability Is the Key Distinction

A central concept in this framework is viability. The authors define living systems as entities that have an intrinsic goal: to avoid death. This goal doesn’t need to be conscious or intelligent. Even the simplest organism behaves in ways that maintain its own continued existence.

This sharply separates life from complex but non-living systems. A hurricane, for instance, has intricate dynamics and consumes enormous amounts of energy, but it has no concern for its own survival. If conditions change and it dissipates, nothing is lost from the system’s point of view.

Living systems, on the other hand, continuously monitor their surroundings. They track food availability, temperature, toxins, and other environmental factors because those variables directly influence their survival. The information they gather and act upon is semantic because it matters.

The Lyfe Framework and the Role of Learning

This paper builds on Bartlett’s broader Lyfe Framework, which aims to describe life in universal terms rather than Earth-specific biology. The framework is made up of four main pillars:

- Dissipation: the use and management of energy

- Autocatalysis: self-sustaining growth and chemical feedback loops

- Homeostasis: maintaining internal stability

- Learning: processing information to improve future viability

The new paper focuses heavily on the fourth pillar, Learning, and provides a precise physical definition of what that means. Learning, in this context, is not intelligence or consciousness. It is the ability of a system to use semantic information to improve its chances of survival over time.

Rethinking the Origin of Life

This informational perspective has important implications for abiogenesis, the study of how life began. Traditionally, scientists have searched for the moment when key molecules like RNA or DNA first appeared. Bartlett’s framework shifts the focus.

Instead of asking when the right molecules formed, the more important question may be when matter first began to process information in a way that enhanced its own viability. This moment, described as an information transition, could mark the true origin of life.

Crucially, this idea is not purely philosophical. The authors propose a way to test it experimentally.

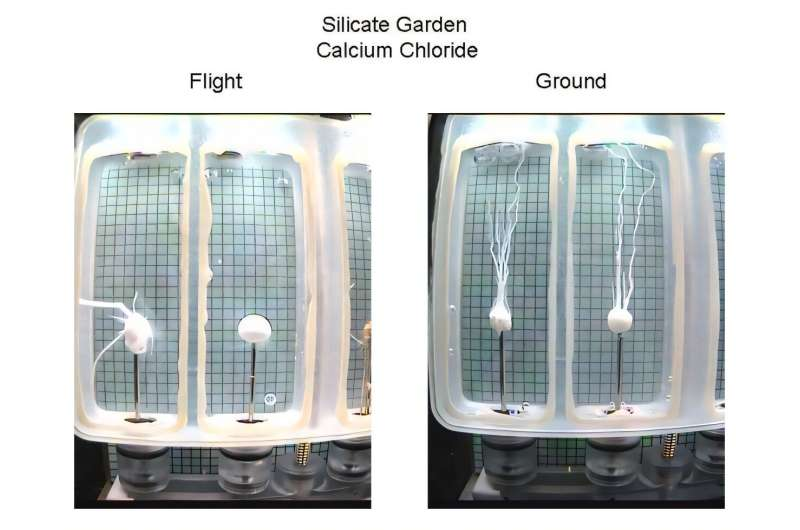

Chemical Gardens and a Falsifiable Test

One proposed test involves structures known as chemical gardens. These are self-assembling mineral structures that form when metal salts are placed in certain solutions. At first glance, they appear to be simple, non-living chemical systems.

The experiment introduces a tool called an Epsilon Machine, an algorithm capable of generating complex patterns while hiding them behind layers of apparent randomness. When this algorithm is connected to a function generator, it produces electrical signals that encode those hidden patterns.

By feeding these signals into a chemical garden and carefully measuring its growth, researchers can check whether the structure begins to mirror the internal state of the Epsilon Machine. If the chemical garden’s internal structure reflects the encoded pattern, it would suggest that the system is processing information, not merely reacting randomly.

This provides a rare thing in origins-of-life research: a falsifiable experimental test.

Physical Limits on the Size of Life

The framework also places constraints on the minimum size of a living cell. For a system to detect its environment and act on semantic information, it must have physical sensors capable of reliable measurement.

According to the paper, physics imposes a lower limit of about 0.4 micrometers in diameter. Below this size, Brownian motion becomes too disruptive. Random collisions with surrounding molecules would spin the cell uncontrollably and introduce too much noise into its sensory data.

This would make it impossible for the cell to reliably detect temperature, chemical gradients, or toxins—leading to actions that harm rather than help viability.

Importantly, this limit is universal. Whether life exists on Earth, Titan, or an exoplanet orbiting another star, the same physical constraints apply.

Implications for Finding Life Beyond Earth

Detecting cells that small across interstellar distances is currently impossible. However, the informational framework suggests alternative approaches.

One idea involves actively probing other planets. If a planet responds to an external signal in a way that increases informational complexity, it may indicate the presence of life. The response does not need to be intelligent or communicative—only non-random and adaptive.

Another promising method comes from Assembly Theory, which examines how complex molecules are constructed. Some molecular structures are so intricate that they are extremely unlikely to form by chance. Their presence could indicate a process driven by information, such as evolution.

Why This Framework Matters

This approach provides a way to think about universal life, not just life as we know it. It helps separate living systems from complex non-living ones and offers new tools for studying the origin and detection of life.

Equally important, it encourages scientists to look beyond familiar biological markers and focus on how systems use information to persist.

The framework is still under debate, and its experimental tests remain to be carried out. But if supported by evidence, it could reshape discussions about life’s beginnings and its possible existence elsewhere in the universe.

Research Paper:

Physics of Life: Exploring Information as a Distinctive Feature of Living Systems

https://journals.aps.org/prxlife/abstract/10.1103/rsx4-8x5f