Lunar Micrometeoroid Storms Pose a Serious Threat to Future Moon Bases

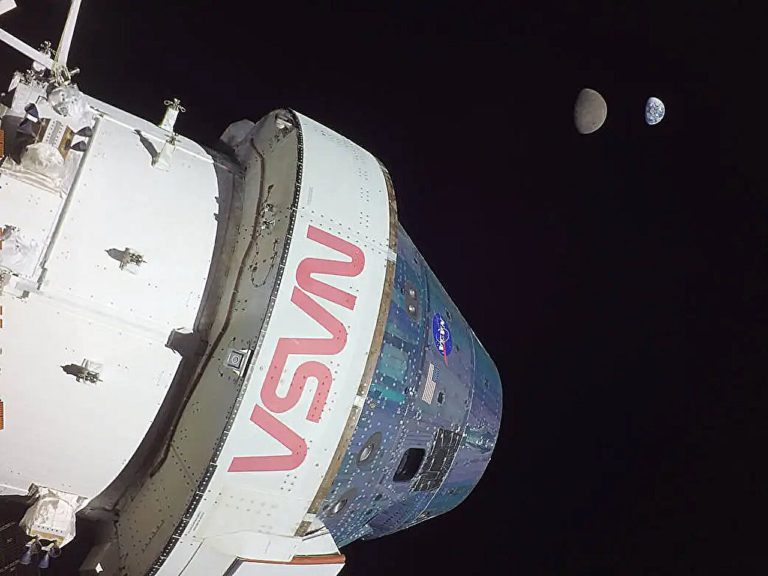

For decades we’ve imagined building long-term homes on the Moon, but one invisible danger has always lurked in the background: micrometeoroids. These are tiny pieces of rock and metal traveling at extraordinary speeds, and a new analysis suggests they may be far more threatening than previously understood. As NASA moves forward with the Artemis program and its plan for a permanent lunar base, researchers are working to quantify exactly what future astronauts will be up against.

A recent study led by Daniel Yahalomi, posted on the arXiv preprint server, takes a detailed look at the intensity of micrometeoroid bombardment across different regions of the lunar surface. The team used NASA’s Meteoroid Engineering Model to estimate how often a lunar base—assumed to be roughly the size of the International Space Station—would be struck by these high-speed particles. Their findings confirm what many space engineers already suspected: the Moon is constantly under attack.

According to the analysis, a lunar outpost of that size would be hit by anywhere between 15,000 and 23,000 micrometeoroids every year. The particles range in mass from a millionth of a gram to about 10 grams. Many are far too small to see with the naked eye, yet because they arrive at speeds up to 70 kilometers per second, even microscopic grains can create zap pits, crater metal, or puncture equipment. On Earth, our thick atmosphere vaporizes nearly all such debris long before it can reach the surface. On the Moon, there is no atmosphere, no wind, and no weather, meaning every incoming particle slams into the surface at full speed.

Interestingly, the danger isn’t uniform. The study reveals that micrometeoroid impact rates vary significantly depending on location. The lunar poles, including the south pole where NASA intends to build its first Artemis base, experience the lowest bombardment levels. This is encouraging, especially since the south pole is already appealing thanks to the presence of water ice, potential near-continuous sunlight in some areas, and good communication visibility with Earth.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the region of the Moon that perpetually faces Earth—the sub-Earth longitude—endures the highest impact rates. Between the safest and most hazardous areas, the study shows a variation factor of roughly 1.6. In practical terms, that means some parts of the Moon are naturally more shielded than others.

Location plays such an important role because of how the Moon interacts with both the Earth and the Sun. The Moon’s orbit and orientation can protect certain areas from specific meteoroid streams while exposing others. Earth’s gravitational influence can also alter the paths of incoming particles, sometimes focusing them toward regions of the Moon rather than shielding them. These dynamics create a complex distribution of micrometeoroid activity that NASA and mission planners must account for.

But even in the best locations, protection systems are not optional. The study examines how Whipple shields, already used on the International Space Station, might function on the lunar surface. These shields consist of an outer bumper layer that breaks up incoming particles and a deeper layer that absorbs the dissipated energy. When an ultrafast particle hits the bumper, it vaporizes or fragments, spreading the impact energy across a wider area before it can reach sensitive equipment.

Using detailed modeling, the researchers established a mathematical relationship describing how many impacts would be expected to penetrate different thicknesses and configurations of shielding. This is crucial because launching material from Earth is expensive, and engineers need precise measurements to avoid overbuilding the shields. Adding unnecessary mass could significantly increase mission costs.

Despite the alarming number of impacts, the study also offers reassurance. With properly designed shielding, the risk of micrometeoroids penetrating a lunar habitat’s defenses can be reduced to extremely low levels. The models allow engineers to determine exactly how thick the shield layers should be to achieve acceptable safety margins—balancing protection with practicality.

The real takeaway is that future astronauts will likely live under a constant, mostly invisible rain of high-speed debris. It won’t be as dramatic as dust storms or meteor showers, but it will be an everyday reality of life on the Moon. Every structure, vehicle, solar panel, and surface component will need to be engineered with this relentless hazard in mind.

Micrometeoroids are a natural part of the space environment, but on the Moon, their effects are magnified by the lack of atmospheric protection. They also vary in composition and structure. Scientists categorize them into multiple types—fine-grained, coarse-grained, scoriaceous, porphyritic, barred olivine, glass, I-type, G-type, and others. Most are silicate-rich and resemble stony material, while a few contain significant amounts of metal. These classifications matter because each type interacts with shielding differently. Some break apart more easily; others stay intact and deliver more concentrated energy on impact.

Understanding micrometeoroid behavior has been a long-standing scientific goal. Apollo missions returned samples with visible pitting on their surfaces, providing early evidence of the damage micrometeoroids can cause. These zap pits, etched into lunar rocks and equipment, are direct reminders that the Moon is far from the tranquil, unchanging landscape it appears to be.

To give readers a broader perspective, it’s worth noting that micrometeoroid impacts also affect spacecraft orbiting Earth. Satellites and the ISS are routinely hit by tiny particles, though Earth’s atmosphere filters out much of the debris before it can reach low-Earth orbit. Still, even in orbit, spacecraft rely on shielding to prevent failure from micrometeoroids and space debris.

On the Moon, however, the absence of natural protection makes the problem significantly more severe. The high velocity of particles is the main concern. At 70 kilometers per second—about 156,000 mph—even a particle weighing 1 microgram can strike with enough force to damage spacecraft materials. That’s a level of kinetic energy we rarely encounter on Earth outside of laboratory experiments.

The upcoming Artemis missions aim to build long-term habitats, mining systems, scientific labs, and other infrastructure. Every component must be able to withstand decades of micrometeoroid bombardment. While the study’s results are sobering, they are also extremely useful. Mission planners now have concrete data to work with, allowing them to design safer habitats and choose locations with naturally lower risk.

This new research adds an important layer of understanding to lunar exploration. The Moon, while close to Earth, remains a harsh environment. Even something as small as a grain of dust can become a threat in the vacuum of space. Yet with careful planning, engineering, and shielding, these dangers can be managed. Understanding these micrometeoroid storms is one more step toward building a sustainable human presence on the lunar surface.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2511.04740