Lunar Soil Studies Reveal How Space Weathering Changes the Moon’s Ultraviolet Reflectance

Scientists studying tiny grains of lunar soil brought back during NASA’s Apollo missions have uncovered new details about how the Moon’s surface changes over time and how those changes affect the way it reflects far-ultraviolet (FUV) light. This research offers important clues for interpreting orbital data, especially when scientists are searching for signs of water ice in the Moon’s permanently shadowed regions.

The study is a collaboration between researchers at Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) and The University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA). By combining advanced laboratory instruments with state-of-the-art microscopy, the team has shown that space weathering plays a major role in shaping how lunar soil interacts with ultraviolet light.

What Space Weathering Means for the Moon

Unlike Earth, the Moon does not have a thick atmosphere or a global magnetic field to shield its surface. Over billions of years, lunar soil has been continuously exposed to solar wind particles and micrometeoroid impacts. This constant bombardment slowly alters the physical and chemical properties of surface grains, a process scientists call space weathering.

Space weathering does not happen overnight. Instead, it gradually changes individual soil grains at the nanoscale. These changes influence how light is absorbed, scattered, and reflected—especially at shorter wavelengths such as the far-ultraviolet, which is invisible to the human eye but extremely valuable for scientific observations.

Revisiting Apollo Samples with Modern Tools

One of the most exciting aspects of this research is that it relies on Apollo-era lunar soil samples, specifically from Apollo 11, Apollo 16, and Apollo 17. These samples were collected between 1969 and 1972 and have been studied for decades. However, modern instruments now allow scientists to extract new information that simply wasn’t accessible in earlier years.

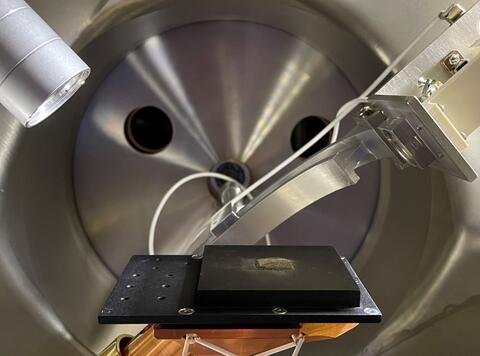

Using SwRI’s Slater Crater ultra-high vacuum instrument suite, the team measured how individual grains reflect far-ultraviolet light. Even more impressively, researchers examined the grains at the atomic level using a high-resolution transmission electron microscope housed at UTSA’s Kleberg Advanced Microscopy Center (KAMC). This microscope is powerful enough to image individual atoms and identify minute chemical features within each grain.

Nanophase Iron Is the Key Player

The analysis revealed a crucial finding: heavily weathered lunar grains develop outer rims filled with nanophase iron particles. These particles are extraordinarily small—about one ten-thousandth the width of a human hair—yet they have a dramatic effect on how the soil reflects ultraviolet light.

Grains with a high concentration of nanophase iron appear darker in the far-ultraviolet and scatter light differently compared to less weathered grains. In contrast, grains that experienced less exposure to space weathering contain far fewer nanophase iron inclusions and reflect more ultraviolet light, making them appear brighter in FUV measurements.

This discovery clearly links the degree of space weathering to changes in ultraviolet reflectance, providing a physical explanation for brightness variations seen in orbital data.

Why Far-Ultraviolet Reflectance Matters

Far-ultraviolet reflectance is not just an academic curiosity. It plays a vital role in interpreting data from spacecraft, particularly NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO). One of LRO’s instruments, the Lyman-Alpha Mapping Project (LAMP), was designed and is led by SwRI scientists.

LAMP observes the Moon using far-ultraviolet light from stars rather than sunlight. This approach allows the instrument to peer into permanently shadowed craters near the lunar poles, regions that never receive direct sunlight and are prime candidates for storing water ice.

To confidently identify ice, scientists must first understand how dry lunar soil reflects ultraviolet light. If space weathering alters that reflectance, it becomes essential to account for those changes. Otherwise, variations caused by weathered soil could be mistaken for hydration or ice signatures.

Improving the Search for Lunar Water Ice

The new findings directly improve scientists’ ability to interpret LAMP data. By understanding how space weathering modifies ultraviolet reflectance, researchers can more accurately isolate signals that may indicate the presence of water ice or hydroxyl compounds.

This is especially important for future lunar exploration. Water ice could support long-term human presence on the Moon by providing drinking water, breathable oxygen, and even rocket fuel. Accurate identification of ice-rich regions depends heavily on precise interpretations of remote sensing data, making this research highly relevant beyond basic lunar science.

Collaboration Across Disciplines

The project highlights a close collaboration between SwRI’s Center for Laboratory Astrophysics and Space Science Experiments (CLASSE) and UTSA’s Kleberg Advanced Microscopy Center. Scientists combined expertise in spectroscopy, planetary science, and nanoscale imaging to connect microscopic grain features with global-scale observations of the Moon.

The research was led by Caleb Gimar, who completed his doctoral work through the joint SwRI–UTSA graduate program, with funding support from NASA’s Lunar Data Analysis Program. The project’s principal investigator was Dr. Ujjwal Raut of SwRI, with additional contributions from experts involved in the LAMP instrument and advanced microscopy.

Why Apollo Samples Still Matter

More than 50 years after the Apollo missions, lunar samples continue to serve as an invaluable scientific resource. Unlike meteorites or remote observations, Apollo samples provide direct physical evidence of the Moon’s surface history.

As analytical techniques improve, these samples reveal new layers of information about surface evolution, radiation exposure, and space weathering processes. This study is a clear example of how revisiting historic samples can lead to fresh insights that directly support modern space missions.

Space Weathering Beyond the Moon

While this research focuses on the Moon, space weathering affects many airless bodies across the solar system, including asteroids, Mercury, and moons of other planets. Understanding how nanophase iron forms and alters reflectance helps scientists interpret observations of these bodies as well.

In fact, lessons learned from lunar soil studies often serve as a benchmark for understanding space weathering throughout the solar system. The Moon’s well-documented samples make it a natural laboratory for studying these universal processes.

A Clearer Picture of the Lunar Surface

By linking atomic-scale features within lunar grains to far-ultraviolet reflectance patterns observed from orbit, this research bridges the gap between laboratory science and planetary exploration. It provides a stronger foundation for interpreting ultraviolet maps of the Moon and improves confidence in identifying valuable resources like water ice.

As new missions prepare to return humans to the Moon and expand robotic exploration, studies like this ensure that scientists are reading the Moon’s surface correctly—down to the smallest grain of dust.

Research Paper Reference:

The Influence of Space Weathering on the Far-Ultraviolet Reflectance of Apollo-Era Soils

Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1029/2025JE009304