Machine Learning Framework LifeTracer Could Transform the Search for Extraterrestrial Life

A new machine learning framework called LifeTracer is gaining attention for its ability to tell apart molecules created by biological processes from those formed through non-biological chemistry. This tool, described in a recent peer-reviewed paper, could become a major asset for analyzing samples from planetary missions—especially as multiple space agencies prepare to return material from Mars, asteroids, and other worlds. The real excitement comes from the fact that LifeTracer doesn’t depend on classic, Earth-centric biomarkers. Instead, it looks at overall chemical patterns, using advanced data analysis and machine learning to spot subtle differences between life-driven chemistry and chemistry that comes purely from physics and geology.

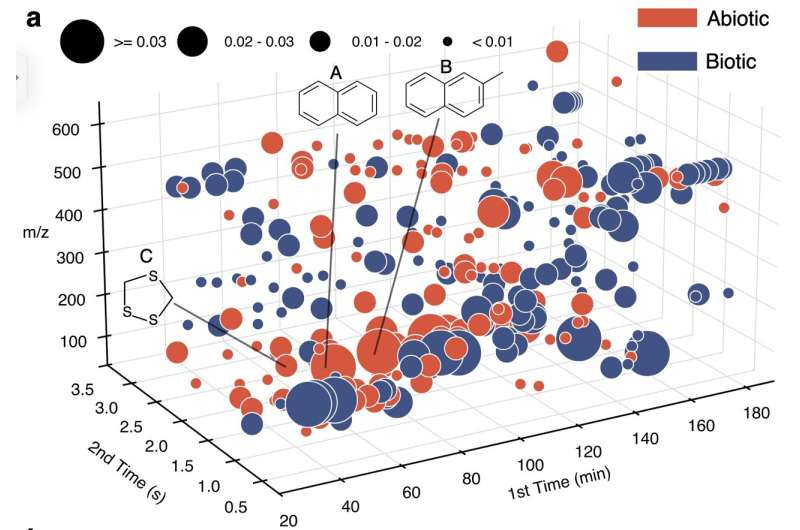

The framework comes from the work of researchers including José C. Aponte, Amirali Aghazadeh, and their collaborators. The team analyzed eight carbonaceous meteorites and ten terrestrial geological samples, processing them with cutting-edge laboratory instrumentation—specifically two-dimensional gas chromatography combined with high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC×GC-HRTOF-MS). This method produces incredibly rich chemical data, revealing thousands of peaks that represent different organic compounds. From this chemically dense dataset, the team built LifeTracer, which trains a model to recognize distinct characteristics that separate abiotic samples from biotic ones.

One of the most interesting outcomes is the scale of information the system handled. The meteorite samples contained 9,475 detected peaks, while the terrestrial samples contained 9,070 peaks. Each peak corresponds to pieces of organic molecules—fragments, ions, or sometimes full compounds—identified through mass spectrometry. LifeTracer processes all of these peaks, identifies patterns, and uses them to classify samples. The model they trained, based on logistic regression, achieved an accuracy of over 87% when distinguishing meteorite-derived organics from terrestrial organic material. That’s impressive considering the vast chemical overlap that can exist between abiotic and biotic organics.

One of the main chemical differences the framework detected involves retention times—that is, how long compounds take to travel through the chromatographic columns in the GC×GC system. Organic molecules in meteorite samples tended to have significantly lower retention times, showing that abiotic organics tend to be more volatile. This makes sense based on existing knowledge: abiotic pathways like photochemistry, irradiation, and inorganic reactions often produce smaller, simpler, more volatile molecules, while biological systems on Earth typically produce longer, more complex, and often less volatile compounds.

LifeTracer also identified specific chemical families as strong indicators. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their alkylated variants played a major role in classification. Among these, naphthalene stood out as the single most predictive compound for identifying abiotic (meteorite) samples. PAHs are commonly found in interstellar dust, comets, and meteorites, so their presence isn’t surprising—but it’s notable that LifeTracer automatically recognized their diagnostic power without being programmed with any assumptions. This ability to spot meaningful patterns without human bias is one of the tool’s major strengths.

For astrobiology, the development of LifeTracer is exciting because it offers a scalable and unbiased way to search for biosignatures. Traditional life-detection strategies often rely on targeted searches for molecules we already know—like amino acids, lipids, or nucleic-acid components. But these biomarkers may not always be present, or they might degrade over time due to radiation, oxidation, or geological processing. LifeTracer moves beyond that limitation by evaluating the overall distribution of organic molecules in a sample, instead of looking for anything specific. This pattern-based approach is well-suited for analyzing material from other planets where life may not follow Earth’s biochemistry.

Another practical advantage is that future sample-return missions will likely bring back complex mixtures of organics. The Mars Sample Return mission, for example, will collect rocks and regolith that may contain a combination of ancient organics, modern contamination, volcanic compounds, or photochemically altered molecules. Interpreting such a mixture manually would be slow and error-prone. A machine learning system like LifeTracer could quickly identify whether the chemical profile shows biotic-like organization or whether it fits patterns more typical of abiotic chemistry.

To give some broader scientific context, the difficulty of distinguishing biotic from abiotic organics is one of the biggest challenges in astrobiology. Many molecules associated with life can also form without life. For example, amino acids and simple hydrocarbons have been found in meteorites, comets, and interstellar clouds. Meanwhile, biological processes often produce messy, diverse mixtures of organics rather than just a few signature compounds. Researchers increasingly believe that patterns—such as molecular diversity, branching patterns in hydrocarbons, or statistical distributions—may serve as more reliable biosignatures than single molecules. LifeTracer fits perfectly into this evolving strategy by focusing on distributions and patterns rather than targeted biomarkers.

Another interesting point is how mass spectrometry, the technology behind the dataset used in this study, has become one of the most important tools for searching for extraterrestrial life. Mass spectrometers can detect extremely small amounts of organic material, identify molecular fragments, and even hint at molecular structures. Planetary missions like NASA’s Perseverance rover, ESA’s Rosalind Franklin rover, and instruments planned for future missions to icy moons often include mass spectrometers for precisely this reason. But raw mass-spectrometry data is incredibly dense, and interpreting it requires sophisticated analysis tools. LifeTracer—or systems built on similar principles—could eventually run on Earth-based labs to quickly analyze returned samples, or perhaps even be adapted to operate directly on spacecraft.

The authors of the study emphasize that tools like LifeTracer don’t automatically “detect life.” Instead, they help classify the origin of organic signatures. A sample classified as “biotic-like” would still need further confirmation, including isotope analysis, environmental context, contamination checks, and structural studies. But such classification dramatically speeds up the process of identifying the most promising samples for deeper investigation.

From a broader perspective, LifeTracer also opens the door to detecting unknown forms of life—or at least recognizing chemical organization that differs from typical abiotic processes. Because the method does not depend on pre-selected biomarkers, it could detect patterns consistent with biology even if the underlying chemistry is unfamiliar. This flexibility is essential when searching for life beyond Earth, where conditions might favor alternative biochemical systems.

In the coming years, with Mars Sample Return, asteroid missions, and potential future sample retrievals from icy worlds like Enceladus or Europa, frameworks like LifeTracer will likely become increasingly important. They provide a way to handle vast, complex chemical datasets rapidly and with reduced human bias. The fact that this early version already performs with more than 87% accuracy is encouraging, and future iterations trained on larger and more diverse datasets may become even more reliable.

The research presents a shift toward a more data-driven, pattern-oriented approach in astrobiology. As humanity gets closer to directly analyzing material from other worlds, having the right analytical tools may determine how quickly—and how confidently—we can identify true biosignatures.

Research Paper:

https://academic.oup.com/pnasnexus/article/4/11/pgaf334/8323799