Meteorite Samples Reveal How the Early Solar System and Planets Like Earth Took Shape

Meteorites may look like ordinary rocks once they land on Earth, but scientists see them as priceless records of the solar system’s earliest history. According to recent research led by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) scientist Thomas Kruijer, meteorites preserve detailed information about how planets formed more than 4.5 billion years ago, long before Earth became the habitable world we know today.

The research, published in the journal Space Science Reviews and set to become part of an upcoming academic textbook, brings together decades of meteorite studies to explain how these space rocks help scientists reconstruct the earliest stages of planet formation. The central question driving this work is simple but profound: how do habitable planets like Earth actually form? Despite major advances in planetary science, this question is still actively debated.

Why Meteorites Matter So Much to Planetary Science

Meteorites are fragments of larger bodies that formed when the solar system was still young. When one streaks across the sky and survives its journey to the ground, it delivers material that has remained largely unchanged since the solar system’s infancy. Scientists describe meteorites as time capsules because they contain chemical and isotopic signatures that record the conditions present when planets were just beginning to assemble.

Many meteorites originate from the asteroid belt, a region between Mars and Jupiter that preserves remnants of early planetary building blocks. These objects never grew large enough to become full planets, which makes them especially valuable. Unlike Earth, they avoided extensive geological recycling, meaning their internal records are still intact.

By studying meteorites in the lab, researchers working in the field of cosmochemistry can determine their ages, compositions, and thermal histories. Some meteorite samples analyzed today are over 4.5 billion years old, making them among the oldest physical objects humans can hold.

From Dust and Gas to Planetesimals

The research outlines a widely supported model of how the solar system formed. It began with a giant molecular cloud of gas and dust that collapsed under gravity, forming the Sun at its center. Surrounding the young Sun was a protoplanetary disk, initially extremely hot and turbulent.

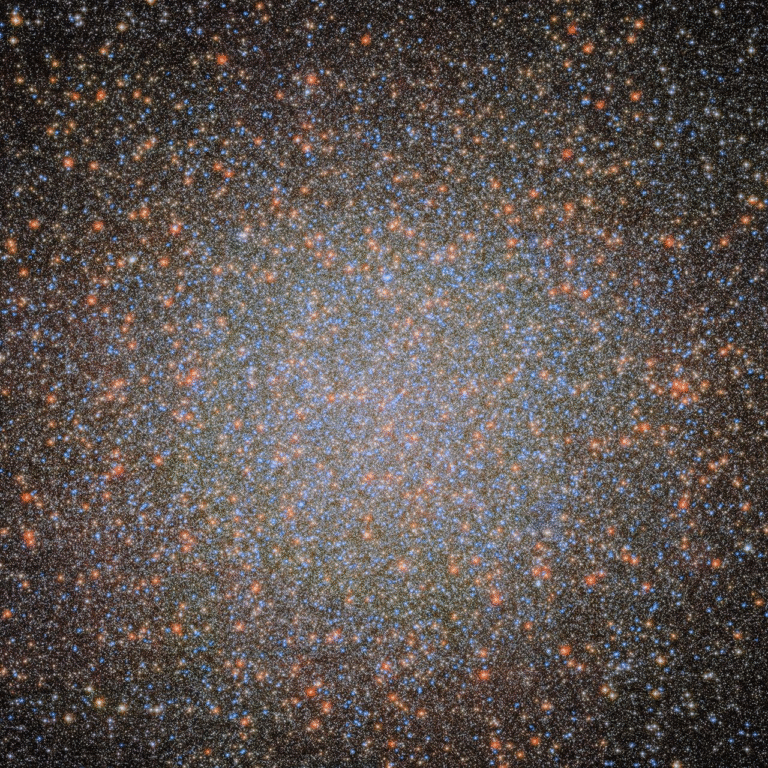

As this disk cooled, tiny dust grains began sticking together. Over time, gravity helped these clumps grow larger and larger, eventually forming small bodies called planetesimals, typically between 1 and 100 miles across. These planetesimals are considered the fundamental building blocks of planets.

Understanding how planetesimals formed is essential, because Earth and the other planets were assembled from countless such objects. Meteorites provide the clearest evidence of what these early building blocks were made of and how quickly they formed.

Undifferentiated Meteorites and the Oldest Solids in the Solar System

One major category discussed in the research is undifferentiated meteorites, also known as chondrites. These meteorites come from planetesimals that never melted or separated into layers. Because of this, they preserve some of the most primitive material in the solar system.

Inside these meteorites are calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions (CAIs), which are believed to be the first solid materials that condensed from the hot protoplanetary disk. CAIs are critical because they serve as a reference point for dating solar system events.

Chondrites also contain chondrules, small spherical grains that formed from molten droplets floating freely in space before being incorporated into larger bodies. Chondrules can be precisely dated, helping scientists determine when specific planetesimals formed and how long planet formation lasted.

Differentiated Meteorites and Clues About Planetary Cores

Not all meteorites remained primitive. Some originated from planetesimals that grew large enough to heat up and melt internally. These are known as differentiated meteorites.

When melting occurred, heavy elements such as iron sank toward the center, forming a core, while lighter materials rose to create a mantle. This process mirrors what happened on Earth, where a dense iron core formed deep beneath the surface.

Iron meteorites, which are fragments of these ancient cores, are especially valuable. Earth’s core is inaccessible, but iron meteorites allow scientists to study core formation directly. By analyzing them, researchers gain insight into how early planetary interiors evolved and how quickly differentiation occurred.

How LLNL Analyzes Meteorite Samples

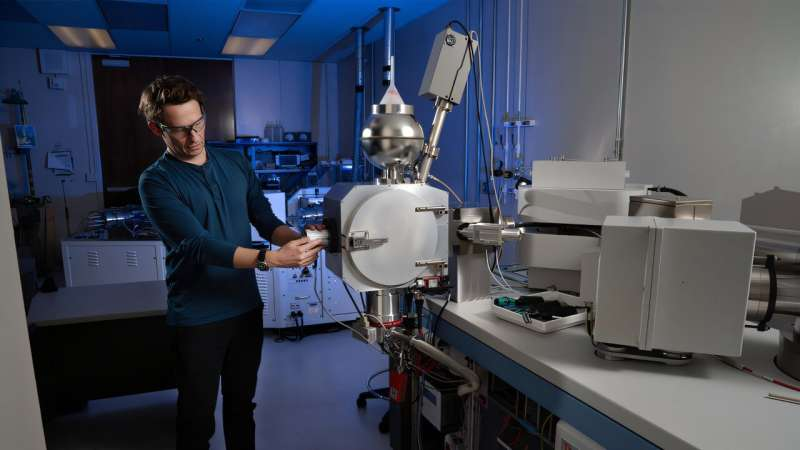

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory plays a major role in this research due to its advanced analytical capabilities. Scientists at LLNL specialize in measuring isotopes, ages, and chemical compositions with extreme precision, even when working with samples no larger than a fingernail.

One key tool used is thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS), which allows researchers to determine the ages of meteorites with remarkable accuracy. These measurements help establish timelines for when different solar system reservoirs formed and how long they remained separate.

These capabilities proved especially important when NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission successfully returned samples from asteroid Bennu. LLNL scientists contributed to analyzing this material, which represents some of the most pristine asteroid samples ever studied.

Preparing for Artemis and Future Lunar Samples

Meteorite research also supports upcoming space missions. Scientists at LLNL are currently analyzing historic lunar samples from the Apollo missions in preparation for new material expected from NASA’s Artemis missions to the Moon.

This work is helping researchers refine analytical techniques and ensure they are ready to handle fresh lunar samples when they arrive. Strengthening these capabilities is a major focus of cosmochemistry research at the laboratory.

Connections to Nuclear Forensics and National Security

Interestingly, the techniques used to study meteorites have applications beyond planetary science. The same high-precision analytical methods are mission-critical for nuclear forensics, a field that aims to determine the origin and history of nuclear materials.

This overlap highlights why cosmochemistry is strategically important. Methods developed to study the oldest rocks in the solar system can also be used to answer modern, real-world questions related to security and materials science.

Feeding Data Into Planet Formation Models

Looking ahead, Kruijer and his collaborators want meteorite data to play a larger role in astrophysical models of the protoplanetary disk. By combining laboratory measurements with large-scale simulations, scientists hope to better understand how planets form and why some become habitable while others do not.

The review paper itself was designed as a comprehensive resource for early-career researchers and scientists from related fields. While summaries and AI-generated overviews can be helpful, carefully curated review papers remain essential for capturing the nuance and precision of planetary science research.

What Meteorites Ultimately Teach Us

Meteorites show that planet formation was not a single, simple event but a complex sequence of processes involving rapid heating, cooling, melting, and mixing. Each meteorite carries a piece of this history, allowing scientists to reconstruct how the solar system evolved from dust and gas into a diverse collection of worlds.

In that sense, holding a meteorite is like holding a fragment of time itself. These ancient rocks remind us that Earth’s story began long before oceans, continents, or life—and that many of the clues to our origins are still falling from the sky.

Research paper reference:

Maria Schönbächler et al., Initial Conditions of Planet Formation: Time Constraints from Small Bodies and the Lifetime of Reservoirs in the Solar Protoplanetary Disk, Space Science Reviews (2025). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-025-01216-z