Mysterious Sky Flashes From the 1950s May Be Linked to Nuclear Tests and Unidentified Aerial Phenomena

A new peer-reviewed study has found an unusual and statistically significant connection between bright, short-lived flashes in the night sky—recorded on old astronomical photographs from the Palomar Observatory between 1949 and 1957—and the timing of nuclear weapons tests and reports of unidentified anomalous phenomena (UAPs).

These strange lights, or “transients,” were discovered by researchers from the Vanishing and Appearing Sources during a Century of Observations (VASCO) project, an international initiative that scans archives of old sky surveys for celestial objects that appear and disappear unexpectedly.

What the Scientists Found

The study, led by Stephen Bruehl and Beatriz Villarroel, was published in Scientific Reports in late October 2025. It analyzed a vast collection of digitized photographic plates taken by the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS-I)—the first comprehensive mapping of the northern sky, completed well before the first satellites were launched.

The team looked at 2,718 days of observations between November 19, 1949, and April 28, 1957, cataloging instances where a star-like object appeared in one exposure but disappeared in subsequent ones. Each of these transients appeared as a bright point of light, showing up on one photographic plate and vanishing by the time the next exposure was taken—sometimes only minutes apart.

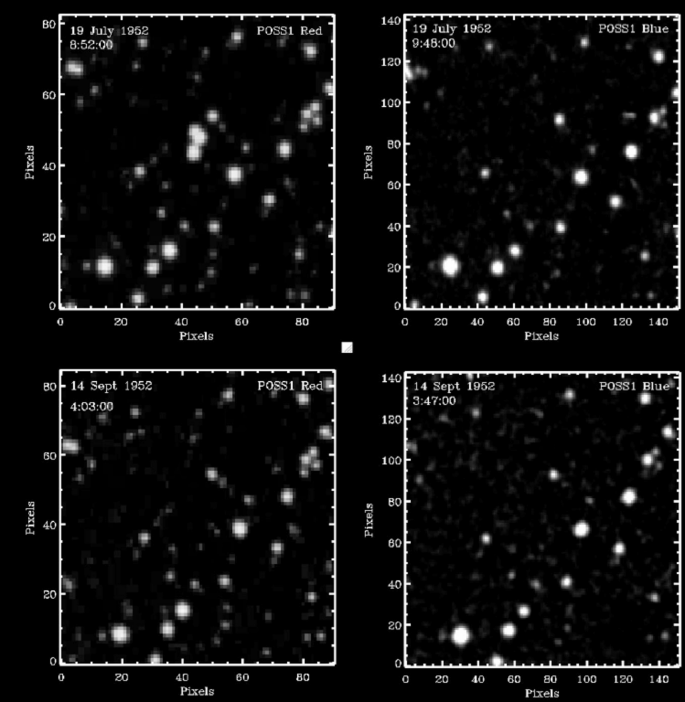

One particularly striking case involved a “triple transient” captured on July 19, 1952. The phenomenon appeared clearly in a red exposure at 8:52 UT, yet when the telescope immediately took a blue exposure just afterward, the object had already vanished. When the same region was imaged again two months later, no trace of the object remained.

When the researchers compared the dates of these fleeting events with the historical record of above-ground nuclear tests and UAP reports, they discovered a surprising statistical correlation.

- Transients were about 45% more likely to appear within one day of a nuclear weapons test.

- On days when UAP sightings were reported, the total number of transients increased noticeably—by about 8.5% for every additional UAP report.

- The study also found that UAP reports themselves were slightly more common during nuclear testing periods.

The scientists stress that these are statistical associations, not proof of direct cause and effect. But the fact that the patterns emerged from a historical dataset collected decades before the modern UFO debate began adds credibility to the findings.

What Exactly Are Transients?

In astronomy, transients are short-lived phenomena—sources of light that appear suddenly and then vanish. They can be caused by things like supernovae, gamma-ray bursts, or asteroid reflections, but the transients seen in these Palomar plates don’t fit any of those patterns.

The POSS-I plates had exposure times of up to 50 minutes, which means these bright spots appeared and disappeared within less than an hour. The images show no trails or streaks, ruling out meteors or satellites. And since they appeared decades before the first artificial satellites (Sputnik launched in 1957), the flashes can’t be explained by man-made objects in orbit.

Some skeptics argue they could simply be defects or dust particles on the photographic plates. However, the researchers point out that it’s extremely unlikely that such random defects would cluster around specific historical dates—particularly those linked to nuclear tests.

Possible Explanations

The study explores several ideas for what might be producing these flashes. None are conclusive, but all are intriguing:

- Atmospheric or radiation effects from nuclear tests – The authors note that high-altitude nuclear detonations could, in theory, create short-lived atmospheric phenomena such as ionization glows or radiation bursts visible from a distance. However, the timing doesn’t fit perfectly: many transients appeared a day after nuclear tests, not immediately afterward.

- Reflections from unknown objects in near-Earth space – Another possibility is that these transients were caused by metallic or reflective objects in orbit or near the upper atmosphere. These could have briefly reflected sunlight toward Earth. This theory gains interest from the long-standing reports of UAPs near nuclear sites, though it remains speculative.

- Instrumental artefacts or emulsion anomalies – While this is the simplest explanation, the researchers argue that the statistical clustering of events makes it hard to attribute all transients to random photographic errors.

Why the Nuclear Connection Is Fascinating

The potential link between nuclear activity and UAPs has appeared in folklore and government reports for decades. Military and intelligence documents have described unusual aerial sightings around atomic test sites and nuclear missile silos, but few academic studies have ever tried to quantify the relationship.

This new analysis offers empirical data suggesting that such a connection—whatever its nature—might be real. The transients were detected independently of any eyewitness accounts or radar systems, relying purely on astronomical imagery taken long before the UFO craze of the late 20th century.

That independence makes the finding particularly interesting to scientists, because it rules out human perception bias. If these flashes were artifacts of people’s imaginations, they wouldn’t show up on physical photographic plates.

How Reliable Is the Study?

While the results are statistically significant, the researchers acknowledge their limitations. The correlation coefficient (ρ ≈ 0.14) between transients and UAP reports indicates only a modest association, not a strong one.

Critics also caution that archival photographic data is tricky to interpret. Old emulsions degrade, and scanning processes can introduce false positives. In fact, a 2024 preprint by astronomers Nigel Hambly and Adam Blair argued that some earlier reports of disappearing stars might actually be digital or emulsion artefacts.

Nevertheless, the Palomar dataset is considered one of the most carefully maintained astronomical archives, and the researchers took steps to rule out known imaging errors. The fact that the same pattern appears repeatedly across multiple observing nights lends weight to their conclusions.

What This Means for Astronomy and UAP Research

If the link between transients, nuclear tests, and UAPs holds up, it could have wide-ranging implications. It may indicate that high-energy human activity (like nuclear detonations) can trigger temporary atmospheric or orbital phenomena. Alternatively, it could mean that objects of unknown origin—possibly artificial—were active near Earth during that era.

The study doesn’t claim extraterrestrial involvement, but it reopens the question of whether some unexplained aerial phenomena might be detectable in astronomical archives.

The authors hope their findings will encourage further investigation using modern high-cadence sky surveys, such as those conducted by the Vera Rubin Observatory. Modern instruments can capture the entire sky every few nights, allowing scientists to check whether similar flashes still occur today—and if they correlate with human activities, natural events, or something else entirely.

A Broader Look at Historical UAP Research

For decades, governments and scientists have wrestled with unexplained aerial sightings, often clustering around sensitive or military areas. In the United States, Project Blue Book (1952–1969) and more recent UAP Task Force investigations have noted a recurring association between UAP reports and nuclear facilities.

Similarly, declassified Soviet documents describe glowing aerial objects seen during nuclear tests in Kazakhstan in the 1950s and 1960s. Some physicists speculate that intense radiation and electromagnetic pulses from nuclear explosions could cause temporary plasma formations—potentially visible as bright, short-lived lights in the upper atmosphere.

The new Palomar study doesn’t claim to have solved that mystery, but it provides the first quantitative evidence linking the two phenomena across historical data.

Why This Study Stands Out

What makes this research unique is its combination of archival astronomy, nuclear history, and modern data analysis. By treating old photographic plates as scientific time capsules, the researchers managed to extract new insights from mid-century observations.

The idea that mysterious lights in the sky could be connected to humanity’s first nuclear experiments is both haunting and thought-provoking. Whether these transients were natural reactions, technological reflections, or something beyond current understanding, the findings invite a fresh look at how we observe the universe—and ourselves.