NASA Scientists Discover a Brand-New Impact Crater on the Moon That Formed in Modern Times

NASA scientists have confirmed that the Moon has gained a new impact crater in the relatively recent past, adding yet another reminder that our nearest celestial neighbor is far from static. Using long-term observations from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC), researchers identified a fresh lunar scar that formed sometime after the spacecraft entered orbit in 2009. While no one witnessed the actual impact, the evidence left behind is unmistakable and scientifically valuable.

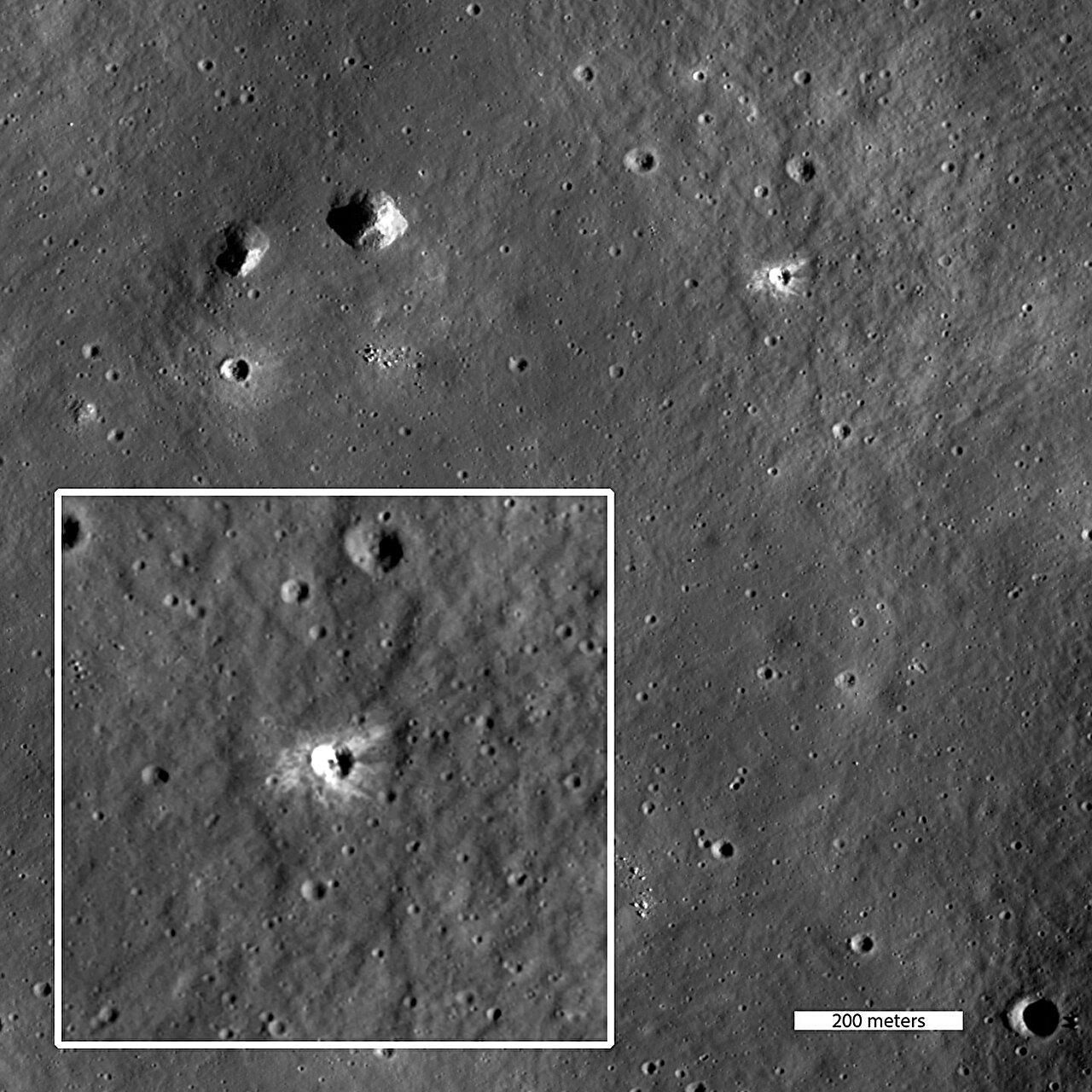

The newly identified crater is located at 26.1941° north latitude and 36.1212° east longitude, in a region of the Moon that has been imaged repeatedly over the years. By carefully comparing older and newer photographs, scientists were able to pinpoint when this crater appeared and study its physical characteristics in detail.

A Fresh Scar on an Ancient Surface

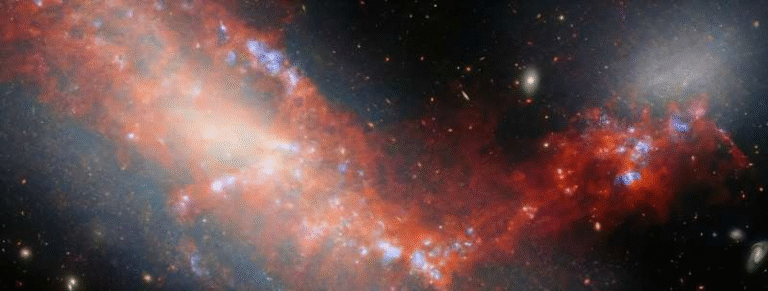

The Moon is around 4.5 billion years old, and its surface records an incredibly long history of collisions. Many of the large, dark basins visible from Earth—often interpreted as the face of the “Man in the Moon”—were formed during a violent period of bombardment that ended roughly 3.8 billion years ago. Those massive impacts shaped the Moon’s most prominent features.

However, impacts never truly stopped. Smaller asteroids and comet fragments continue to strike the Moon even today, carving out new craters on a much smaller scale. The newly discovered crater is one such example. Measuring about 22 meters (72 feet) in diameter, it is roughly the size of a large house. While modest compared to ancient lunar basins, it stands out because of its remarkably bright appearance.

How Scientists Found the Crater Without Seeing the Impact

Detecting new craters on the Moon is not as simple as pointing a telescope at the sky. Instead, the LROC team relies on systematic image comparisons. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has been circling the Moon since 2009, repeatedly photographing the same regions under similar lighting conditions.

In this case, scientists compared images taken before December 2009 with those captured after December 2012. The crater was absent in earlier images and clearly visible in later ones, allowing researchers to narrow down the time window during which the impact occurred. Although the collision itself went unnoticed, the aftermath left a clear signature that could not be missed.

This method has become one of the most reliable ways to track ongoing geological change on the Moon.

Why the Crater Looks So Bright

What makes this crater especially striking is not its size but its bright ejecta rays. When the impact occurred, material from beneath the lunar surface was blasted outward, spreading tens of meters from the crater rim in a starburst-like pattern. This freshly exposed material reflects sunlight much more efficiently than the surrounding older soil, making the crater appear dramatically brighter in orbital images.

Over time, this brightness will fade. The Moon has no atmosphere, but its surface is constantly altered by space weathering—a combination of solar wind particles, micrometeorite impacts, and cosmic radiation. These processes slowly darken exposed material. As a result, the bright rays surrounding this crater will gradually blend into the background over thousands to millions of years.

This is the same reason why relatively young craters like Tycho, which formed around 108 million years ago, still display prominent ray systems visible from Earth, while older craters appear far more subdued.

Why Discovering New Craters Matters

Finding fresh lunar craters is not just visually interesting—it serves several important scientific purposes.

First, it helps researchers refine estimates of the current impact rate on the Moon. Understanding how often objects strike the lunar surface is essential for assessing risks to robotic spacecraft and future human explorers, particularly as agencies plan long-term missions under programs like NASA’s Artemis initiative.

Second, newly formed craters provide a natural laboratory for studying how quickly lunar features degrade. By tracking how bright rays darken and how sharp crater edges soften over time, scientists can improve their models for dating other lunar surfaces. This, in turn, helps build a more accurate timeline of the Moon’s geological history.

The Moon Is Still Changing

One of the most compelling takeaways from this discovery is the reminder that the Moon is not frozen in time. Although it appears calm and unchanging when viewed from Earth, it is still being shaped by external forces. The steady rain of small impacts continues to modify its surface, even on timescales short enough for modern spacecraft to detect.

The LROC mission has already identified hundreds of recent impact craters, and this number continues to grow as image archives expand. Each new crater adds another data point that helps scientists understand how airless bodies evolve across the solar system.

How Lunar Craters Help Us Study Other Worlds

The Moon plays a crucial role as a reference point for planetary science. Because it lacks erosion from wind or water, its surface preserves impact features far better than Earth’s. By studying crater formation and aging on the Moon, scientists can apply similar principles to Mars, Mercury, and icy moons elsewhere in the solar system.

In many ways, the Moon acts as a calibration tool for understanding impact processes throughout space. Every new crater, including this recently identified one, sharpens that tool.

Looking Ahead

As lunar exploration ramps up in the coming decades, discoveries like this highlight the importance of continued monitoring. High-resolution imaging not only helps protect future missions but also deepens our understanding of how dynamic the solar system remains, even billions of years after its formation.

The Moon may look familiar, but it is still quietly collecting new scars as it travels through space—a subtle but powerful reminder that change never truly stops.

Research reference:

https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JE003970