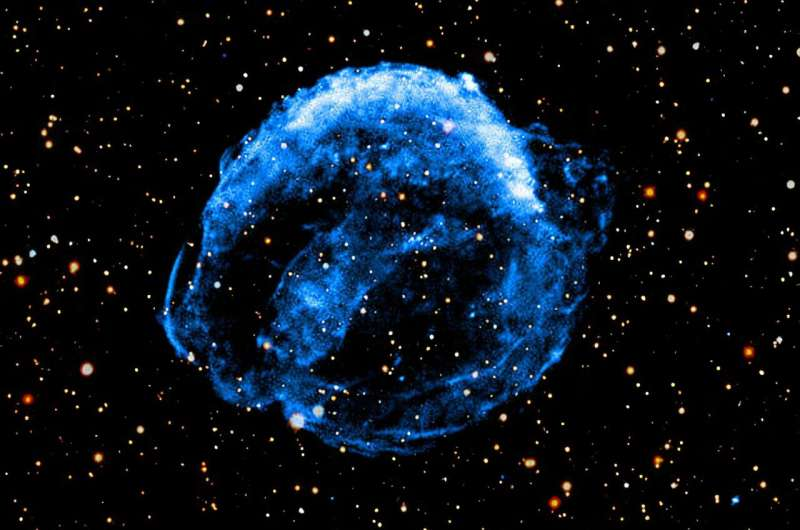

NASA’s Chandra Turns 25 Years of Data into a Stunning Video of Kepler’s Supernova Remnant

NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory has released a remarkable new video that shows the slow but powerful evolution of Kepler’s Supernova Remnant, built from X-ray observations collected over more than two and a half decades. This is not just a visually striking release—it is also a scientifically rich look at how the debris from a stellar explosion changes as it crashes through space over time.

The video is created using Chandra data taken in 2000, 2004, 2006, 2014, and 2025, making it the longest time-span video ever released by the Chandra mission. The sheer length of this observational record is important, because it allows astronomers to directly measure motion, expansion, and structural changes in the remnant rather than inferring them from still images.

Kepler’s Supernova Remnant is the leftover debris from a stellar explosion that was first seen by human observers in 1604, making it the most recent supernova visible to the naked eye from Earth. Today, more than four centuries later, scientists are still uncovering new details about that explosion and the environment in which it occurred.

What Makes This New Chandra Video Special

Supernova remnants evolve slowly on human timescales, which means that meaningful changes usually require observations spread over many years. Chandra’s sharp X-ray vision and long operational life make it uniquely capable of capturing this kind of evolution.

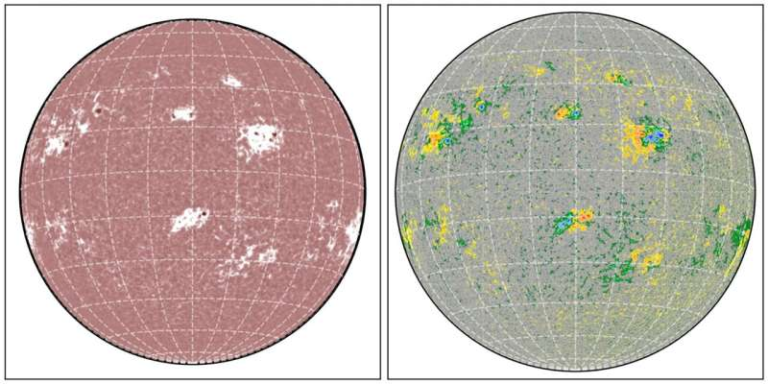

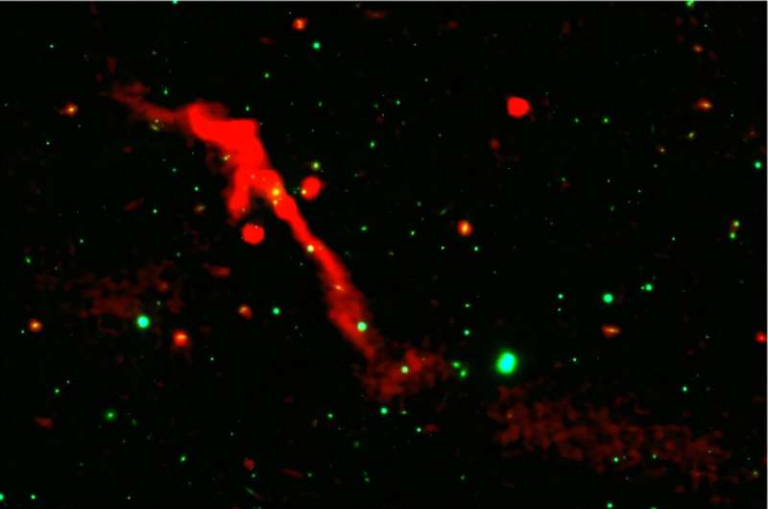

In the newly released video, X-ray data from Chandra is combined with optical observations from Pan-STARRS, allowing viewers to see both the hot, high-energy debris glowing in X-rays and the cooler material visible in optical light. The X-rays trace gas heated to millions of degrees, revealing shock fronts and fast-moving debris that cannot be seen with optical telescopes alone.

Because the video spans over 25 years, astronomers can clearly see how different parts of the remnant expand at different speeds and in different directions. This kind of long-term, high-resolution dataset is extremely rare in astronomy and highlights the value of maintaining space observatories for decades rather than just a few years.

A Quick History of Kepler’s Supernova

The original explosion was recorded in 1604 and carefully studied by Johannes Kepler, after whom the remnant is named. Modern astronomy has since revealed that this explosion was a Type Ia supernova.

Type Ia supernovae occur when a white dwarf star exceeds a critical mass. This can happen either by pulling material from a companion star or by merging with another white dwarf. Once that mass limit is crossed, the star undergoes a runaway thermonuclear explosion.

These events are especially important because Type Ia supernovae have very similar intrinsic brightness. Astronomers use them as cosmic distance markers, helping measure how fast the universe is expanding. In fact, observations of Type Ia supernovae played a key role in discovering that the expansion of the universe is accelerating.

Kepler’s Supernova Remnant is located about 17,000 light-years from Earth, well within our own Milky Way galaxy. Its relative closeness allows Chandra to capture fine details in the structure of the debris.

Measuring Speed, Direction, and Environment

One of the most interesting findings highlighted by the video is the huge variation in expansion speeds across the remnant.

The fastest-moving regions of the debris are traveling at around 13.8 million miles per hour, which is roughly 2% of the speed of light. These fast components are moving toward the bottom of the image shown in the video.

In contrast, the slowest regions are expanding at about 4 million miles per hour, or roughly 0.5% of the speed of light, and are moving toward the top of the image.

This difference is not random. Astronomers believe it is caused by variations in the density of the surrounding gas. Where the supernova debris runs into denser material, it slows down more quickly. Where the surrounding space is thinner, the debris can race ahead at much higher speeds.

By tracking these differences, scientists gain valuable information about the environment around the star before it exploded, as well as how material ejected by supernovae interacts with the interstellar medium.

Studying the Blast Wave in Detail

The research team also focused on the blast wave, which is the leading edge of the expanding explosion. This is the first part of the remnant to collide with material outside the original star.

By measuring both the width of the blast wave and how fast it is moving, astronomers can extract clues about the energy of the explosion and the nature of the surrounding gas. A thinner or thicker blast wave can indicate differences in density, magnetic fields, and particle acceleration processes.

These measurements are only possible because Chandra can repeatedly image the same object with exceptional clarity over long periods of time.

Why Supernova Remnants Matter

Supernova remnants like this one are not just cosmic leftovers—they play a central role in shaping galaxies.

When a star explodes, it hurls heavy elements such as iron, silicon, and oxygen into space. These elements later become part of new stars, planets, and potentially life itself. Without supernovae, the universe would lack many of the chemical building blocks we take for granted.

Supernova shock waves can also trigger new star formation by compressing nearby gas clouds. At the same time, they can heat and stir the interstellar medium, influencing how galaxies evolve over billions of years.

Kepler’s Supernova Remnant is especially valuable because it comes from a Type Ia explosion, allowing scientists to connect detailed remnant physics with the kinds of supernovae used to study the expansion of the universe.

The Value of Chandra’s Longevity

This release also highlights something easy to overlook: long-lived space missions matter. Chandra was launched in 1999, and its ability to return to the same targets year after year has enabled studies that simply would not be possible with short-duration missions.

The Kepler video is a clear example of how time itself becomes a scientific tool. Watching a supernova remnant change over decades turns abstract models into observable reality.

The findings and the video were presented at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, where researchers shared both the visual results and the detailed analysis behind them.

Research Reference

Chandra X-ray Center / NASA. “Supernova Remnant Video from NASA’s Chandra Is Decades in the Making.” American Astronomical Society Meeting 247, January 2026.

https://chandra.si.edu/press/26_releases/press_010626.html