NASA’s Roman Space Telescope Could Unlock a Massive New Wave of Insights Into the Milky Way’s Stars

NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is on track to deliver an unprecedented amount of information about stars in our galaxy—especially the dense, dust-obscured region at the Milky Way’s center. A new study confirms that Roman will be able to perform asteroseismology—the science of measuring stellar oscillations—on more than 300,000 stars, making it the largest asteroseismic dataset ever collected. This capability comes as a bonus on top of Roman’s main scientific goals, and researchers are now confident that the telescope’s design and survey cadence naturally enable it.

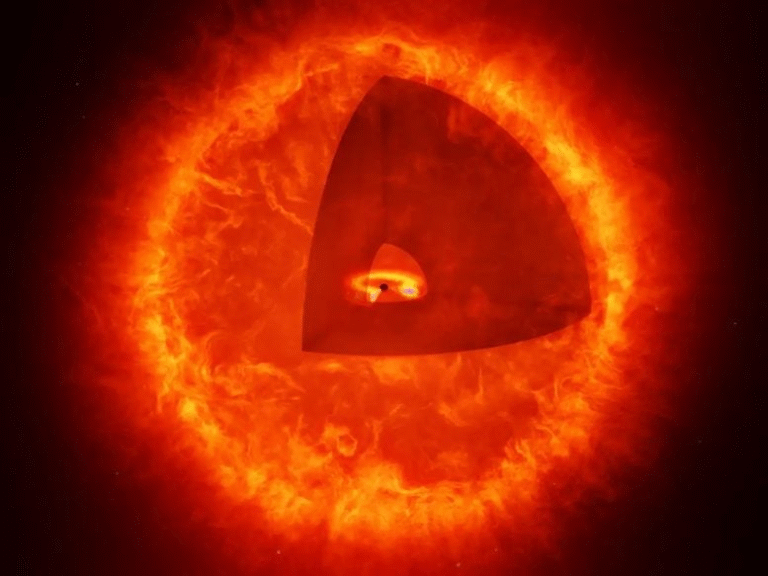

Asteroseismology works by tracking subtle brightness variations caused by waves moving inside stars. These oscillations reveal key properties such as age, mass, and radius. NASA’s previous Kepler mission detected oscillations in about 16,000 stars over its lifetime. Roman, thanks to its wider field of view and rapid observing schedule, is expected to exceed that number by a huge margin without requiring any mission modifications.

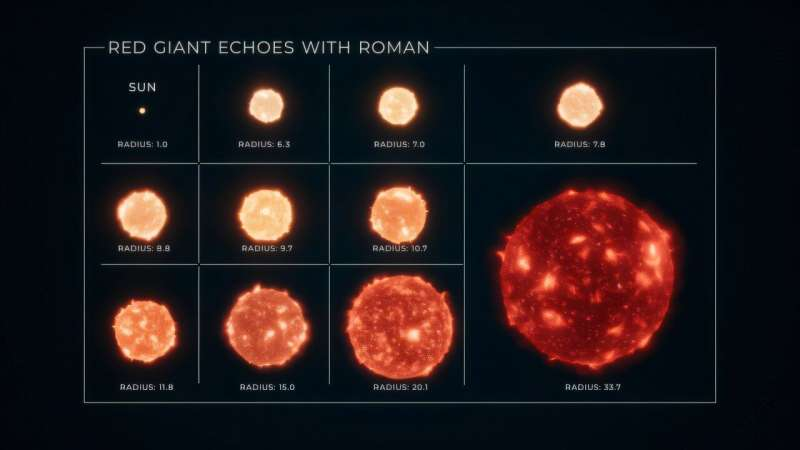

A team of astronomers tested Roman’s asteroseismic potential by taking real Kepler data and degrading it to match Roman’s expected noise levels, filters, and cadence. After adjusting the data—such as increasing the observation frequency and shifting the wavelength range—they calculated the probability of Roman detecting oscillations in different types of stars. The results confirmed that Roman can reliably capture oscillations in red giant branch and red clump stars, which are bright, evolved stars abundant in the galactic bulge.

These stars are ideal for Roman’s observation strategy. The Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey (GBTDS) will repeatedly observe the Milky Way’s center every 12 minutes, across six separate 70.5-day campaigns, shortly after the telescope launches. Since red giant oscillations occur over hours to days, Roman’s cadence lines up perfectly.

The research team then combined the detection probabilities with a realistic model of the Milky Way. Their initial estimate suggested a lower limit of 290,000 detectable stars, with 185,000 located in the bulge itself. Once the survey cadence was finalized at 12 minutes, the number rose above 300,000 stars, making the dataset far larger than anything obtained before. These measurements will help refine our understanding of stellar evolution and provide a deep look into regions of the galaxy that have been historically difficult to study due to heavy dust.

One major benefit of this enormous dataset is its connection to exoplanet science, one of Roman’s core mission areas. Roman will discover exoplanets through microlensing, a technique where a foreground star’s gravity magnifies the light from a background star. The presence of a planet creates a distinct signal in this magnification. Asteroseismology will allow astronomers to better characterize the host stars of these microlensing planets—helping determine the stars’ ages and chemical compositions. This information provides essential context for understanding the planets themselves.

Knowing the age and metallicity of exoplanet host stars is particularly important because it helps astronomers interpret how planetary systems form, how long they survive, and how they evolve as their stars age and expand. For many microlensed systems, these properties would normally be extremely hard to measure. Roman’s massive asteroseismic sample will enable researchers to build statistical profiles of typical bulge and disk star populations, which exoplanet scientists can use to better characterize detected planetary systems.

Beyond exoplanets, Roman’s data will provide crucial clues about the Milky Way’s formation and history. The galactic bulge is notoriously difficult to study because dust blocks visible light, but Roman will observe in infrared, allowing it to see through the dust. Scientists have long debated whether the bulge is primarily composed of ancient stars or contains surprisingly young populations. Roman’s ability to measure ages for hundreds of thousands of stars will help settle these debates and may reveal unexpected trends in chemical composition or stellar evolution.

Researchers are already preparing catalogs and target lists ahead of Roman’s launch. These lists will be used to validate the telescope’s early performance and help guide early observations. Since Roman’s bulge survey begins soon after the telescope becomes operational, the team aims to make the most of the first available data.

Roman is scheduled to launch no later than May 2027, though NASA is working toward an earlier launch window as soon as fall 2026. Once in orbit, it will begin a mission designed to advance fields ranging from dark energy to exoplanets. Asteroseismology, while not among its original primary goals, is now emerging as one of the most scientifically exciting capabilities the mission will offer.

With its wide field of view—roughly 100 times that of the Hubble Space Telescope—and fine cadence, Roman will open a new window on stellar populations that have been inaccessible for decades. The scale of the asteroseismic dataset alone could reshape models of stellar evolution and deepen our understanding of the structure of the galaxy.

Understanding Asteroseismology (Extra Information for Readers)

Asteroseismology is often compared to seismology on Earth. Just as earthquakes reveal the internal structure of our planet, stellar oscillations reveal the internal structure of stars. These waves are caused by turbulence in the outer layers of stars, and they travel through the stellar interior before reaching the surface as tiny fluctuations in brightness.

By studying these frequency patterns, astronomers can determine:

- Mass – essential for understanding how stars evolve

- Radius – useful for measuring luminosity and comparing star types

- Age – one of the hardest properties to measure directly

- Internal structure – which provides insights into how stars burn fuel

Red giants are especially helpful because they are bright and their oscillations are strong enough to be detected even in crowded or dusty regions.

NASA’s Kepler and TESS missions pioneered space-based asteroseismology, but Roman’s combination of large field, infrared sensitivity, and rapid sampling offers a completely different scale of data collection.

Why the Milky Way Bulge Is Important (Extra Information for Readers)

The galactic bulge is the densely packed region of stars surrounding the center of the Milky Way. Studying it matters because:

- It contains some of the oldest stars in the galaxy.

- Its structure holds clues about how the Milky Way formed—whether through mergers, slow accumulation of matter, or rapid early collapse.

- It’s heavily obscured by dust, making traditional optical observations difficult.

- It has a rich mix of red giant and red clump stars—perfect for asteroseismology.

Infrared telescopes like Roman can penetrate dust and reveal stars hidden from visible-light observatories.

Roman’s bulge survey will be one of the most detailed astronomical observations ever conducted, covering hundreds of millions of stars. Even outside of asteroseismology, it will provide data for mapping dark matter distributions, measuring stellar motions, and discovering thousands of exoplanets through microlensing.

Research Reference

Modeling Asteroseismic Yields for the Roman Galactic Bulge Time-domain Survey

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/adde5b