NASA’s Roman Space Telescope Is Preparing an Ambitious Plan to Map the Milky Way in Unprecedented Detail

NASA is gearing up for one of its most detailed explorations of our home galaxy yet. The agency has officially outlined plans for a massive observational effort using the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, a next-generation infrared observatory designed to survey large areas of the sky with exceptional clarity. This project, known as the Galactic Plane Survey, aims to reveal the Milky Way in ways astronomers have never been able to see before.

At its core, this survey is about scale, depth, and access to regions of the galaxy that have long remained hidden. By combining wide-field imaging, infrared vision, and repeated observations, Roman is expected to map tens of billions of stars, uncover new galactic structures, and significantly improve our understanding of how the Milky Way formed and continues to evolve.

What the Galactic Plane Survey Will Do

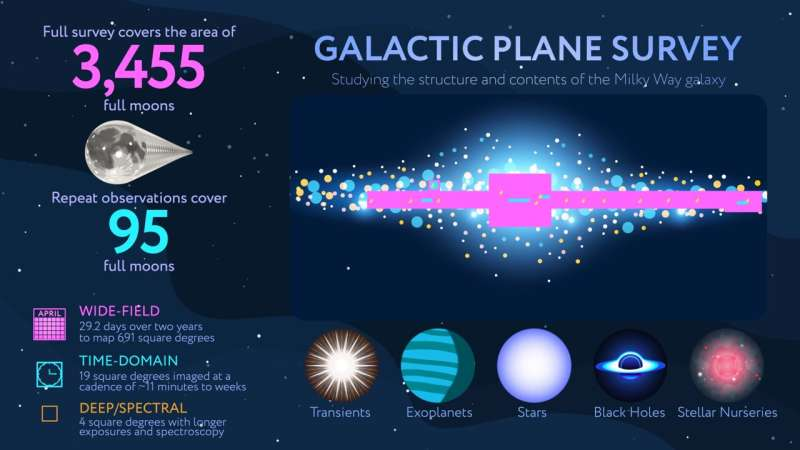

The Galactic Plane Survey is Roman’s first selected general astrophysics survey, marking an important milestone for the mission. While Roman already has three core surveys planned, this effort stands out because of its sheer ambition and its focus on the densest, most complex parts of our galaxy.

The survey will take place over 29 total days of observations, spread across the first two years of Roman’s five-year primary mission. During that time, Roman will focus on the galactic plane—the bright, dusty band of stars that stretches across the night sky and represents our edge-on view of the Milky Way’s disk.

This region contains most of the galaxy’s stars, gas, and dust, but it is also the hardest area to study from Earth because thick clouds of dust block visible light. Roman’s infrared instruments are specifically designed to cut through this dust, revealing what lies beneath.

The Survey’s Three Main Components

NASA’s plan breaks the Galactic Plane Survey into three distinct observational parts, each serving a different scientific purpose.

The primary component will cover 691 square degrees of sky, an area equivalent to roughly 3,500 full moons. This portion alone will take about 22.5 days of observing time and will provide a broad, high-resolution map of the Milky Way’s disk.

The second component focuses on a smaller region of 19 square degrees, about the size of 95 full moons, which Roman will observe repeatedly over 5.5 days. These repeated observations are crucial for studying objects that change over time, such as flickering stars, stellar explosions, and gravitational microlensing events.

The final component consists of several even smaller fields, adding up to around 4 square degrees and 31 total hours of observations. These regions will be studied using Roman’s full suite of filters and spectroscopic tools, allowing astronomers to analyze stars and other objects in exceptional detail.

Seeing the Galaxy Through Infrared Eyes

One of Roman’s most powerful advantages is its ability to observe the universe in infrared light. While missions like the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft have already mapped around 2 billion stars in visible light, Gaia struggled with regions heavily obscured by dust.

Roman’s infrared “heat vision” can penetrate these dusty regions, opening up vast areas of the Milky Way that have never been properly explored. This includes the far side of the galaxy, the central bar, and the crowded core, where stars are packed tightly together.

By combining infrared sensitivity with Roman’s wide field of view and sharp resolution, astronomers expect to detect up to 20 billion stars, tracking subtle shifts in their positions over time. These measurements will help scientists map stellar motions and reconstruct the galaxy’s structure in three dimensions.

A New Window into Star Birth and Evolution

One of the most exciting aspects of the Galactic Plane Survey is its potential to transform our understanding of star formation. Stars are born inside dense clouds of gas and dust, which are notoriously difficult to study with visible-light telescopes.

Roman will peer deep into these stellar nurseries, identifying millions of young stars at various stages of development. This includes stellar embryos still embedded in their birth clouds, unstable young stars that flare unpredictably, and slightly older stars that may already host forming planetary systems.

By observing so many stars across different environments, astronomers will be able to study how forces like gravity, radiation, magnetism, and turbulence shape stellar evolution. The survey will also help determine why some gas clouds form massive stars, while others produce brown dwarfs or fail to ignite at all.

Clusters, Spiral Arms, and Galactic History

The survey will closely examine nearly 2,000 young open clusters, loosely bound groups of stars that form together. These clusters are especially useful for understanding how the Milky Way’s spiral arms trigger bursts of star formation.

Roman will also map dozens of ancient globular clusters near the galaxy’s center. These tightly packed collections of old stars act like cosmic fossils, preserving clues about the Milky Way’s earliest epochs.

Because stars in a cluster share the same age and chemical composition, comparing clusters across the galaxy allows astronomers to isolate environmental effects with remarkable precision. This helps answer long-standing questions about how location influences stellar life cycles.

Hunting Invisible Objects with Microlensing

The Galactic Plane Survey will also play a key role in detecting dark and compact objects using a technique called gravitational microlensing. When a massive object passes in front of a distant star, its gravity bends and magnifies the star’s light, causing a temporary brightening.

By capturing these events, Roman can detect isolated white dwarfs, neutron stars, and black holes, even when they emit no light of their own. This is particularly valuable for understanding the population of stellar remnants scattered throughout the galaxy.

Repeated observations will also help identify compact binary systems, which are important because they can eventually merge and produce gravitational waves, ripples in space-time detected by observatories on Earth.

Measuring the Galaxy More Accurately Than Ever

Roman will monitor stars that pulse rhythmically, such as Cepheid variables, whose brightness changes are directly linked to their true luminosity. By comparing how bright these stars appear to how bright they actually are, astronomers can calculate distances across the galaxy with greater accuracy.

Finding these pulsating stars at larger distances and tracking them over time will help refine the cosmic distance scale, improving measurements not only within the Milky Way but also for nearby galaxies.

How This Fits Into Roman’s Bigger Mission

The Galactic Plane Survey is just one part of Roman’s broader scientific agenda. At least 25% of the telescope’s five-year mission is reserved for astronomers around the world to propose additional surveys and experiments, ensuring the observatory remains flexible and community-driven.

Roman is currently scheduled to launch no later than May 2027, with teams working toward a possible fall 2026 launch. Once operational, the telescope is expected to generate enormous public data sets that will support research for decades.

Why This Survey Matters

Together, Roman’s wide coverage, infrared vision, and time-domain observations will produce what many scientists describe as the most complete portrait of the Milky Way ever created. By revealing hidden stars, mapping the galaxy’s structure, and tracking how objects change over time, the Galactic Plane Survey will reshape how we understand our cosmic neighborhood.

Research reference:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.04588