NASA’s Webb Telescope Delivers an Unprecedented Look Into the Heart of the Circinus Galaxy

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has provided the most detailed view ever captured of the central region of the Circinus galaxy, a nearby spiral galaxy located about 13 million light-years away. At the center of this galaxy lies an active supermassive black hole, and Webb’s latest observations are reshaping long-standing ideas about how such black holes are fed and how they influence their host galaxies.

For decades, astronomers believed that much of the intense infrared radiation coming from the centers of active galaxies like Circinus was produced by outflows—streams of extremely hot material blasted outward from the vicinity of the black hole. Webb’s new data tells a very different story. Instead of being dominated by outflows, the majority of this infrared emission is now shown to originate from hot dust spiraling inward, actively feeding the black hole itself.

This breakthrough comes from Webb’s ability to peer through dense clouds of dust that previously blocked astronomers’ view, combined with a cutting-edge imaging technique that delivers extraordinary resolution. The findings were published in Nature Communications and represent one of the sharpest looks ever taken at the immediate surroundings of a supermassive black hole.

The Circinus Galaxy and Its Active Core

The Circinus galaxy is classified as a nearby spiral galaxy and is well known among astronomers for hosting an active galactic nucleus (AGN). At its center sits a supermassive black hole that continues to shape the galaxy’s evolution by pulling in gas and dust from its surroundings.

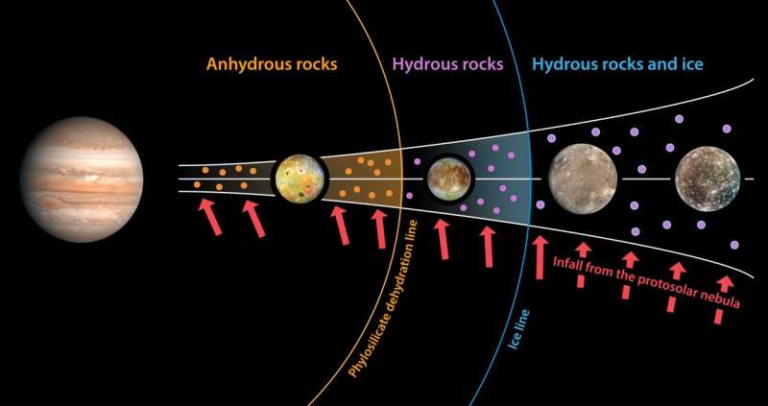

In active galaxies like Circinus, matter does not fall straight into the black hole. Instead, gas and dust collect into a thick, donut-shaped structure called a torus. As material from the inner edge of this torus spirals inward, it forms an accretion disk, heating up through friction and emitting enormous amounts of energy across the electromagnetic spectrum.

The problem astronomers faced for years was that the densest regions around the black hole are heavily obscured. Bright starlight from the surrounding galaxy and thick dust clouds made it nearly impossible for ground-based telescopes to resolve where different types of emissions were actually coming from. This led to models that relied on indirect measurements and left key questions unanswered.

Why Earlier Models Fell Short

Before Webb, astronomers had to piece together data from multiple telescopes operating at different wavelengths. These observations could detect infrared excess near the galaxy’s core, but they lacked the resolution to pinpoint its exact source.

As a result, theoretical models often treated emissions from the torus, the accretion disk, and the outflows separately. Many of these models concluded that the bulk of the infrared light—and therefore much of the mass near the black hole—came from outflowing material.

This assumption persisted for decades, largely because there was no way to directly resolve the central region in enough detail. Excess infrared emission detected since the 1990s could not be fully explained by models that considered only the torus or only the outflows, leaving astronomers with an incomplete picture.

Webb’s Game-Changing Imaging Technique

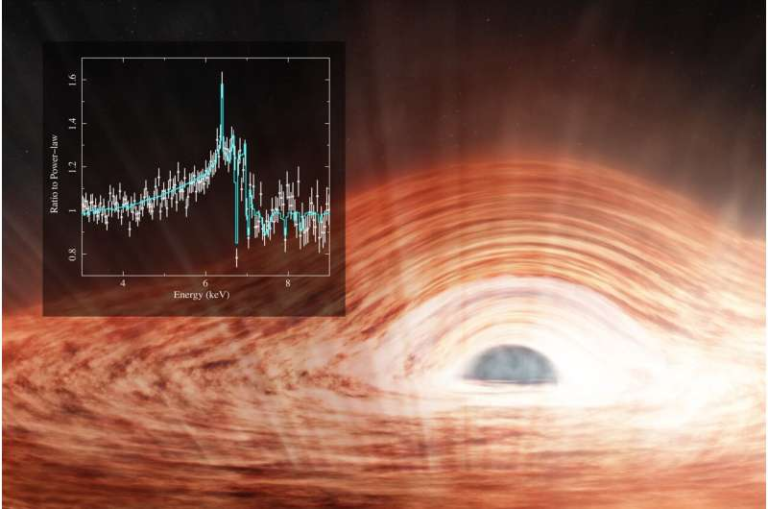

The turning point came with Webb’s use of the Aperture Masking Interferometer (AMI) mode on its NIRISS (Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph) instrument. Interferometry is a powerful technique that combines light in such a way that fine details can be reconstructed far beyond what a single telescope mirror would normally allow.

In Webb’s case, the AMI uses a special mask containing seven small hexagonal holes placed over the telescope’s aperture. Each hole acts like a tiny telescope, and the light collected through them creates interference patterns on the detector. By analyzing these patterns, astronomers can reconstruct images with extremely high resolution.

This approach effectively turns Webb into a space-based interferometer, achieving the equivalent resolution of a 13-meter telescope instead of Webb’s actual 6.5-meter mirror. Importantly, this marked the first extragalactic observation ever made using an infrared interferometer in space.

What the New Data Revealed

With this unprecedented level of detail, the research team was able to isolate where the infrared emission around Circinus’s black hole was truly coming from. The results were striking.

About 87% of the infrared emission from hot dust originates in the innermost regions close to the black hole, specifically from the dusty torus feeding it. Less than 1% of the emission comes from hot dusty outflows, overturning previous assumptions. The remaining 12% arises from regions farther out, which earlier observations could not distinguish clearly.

Webb’s images show the inner face of the torus glowing brightly in infrared light, while darker regions indicate where the outer parts of the torus block light. This provides direct visual confirmation of how matter is structured and funneled toward the black hole.

Why This Discovery Matters

This finding solves a long-standing mystery about infrared excess emissions in active galaxies. For the first time, astronomers can confidently say that, at least in the case of Circinus, these emissions are dominated by material feeding the black hole, not by matter being expelled from it.

It also highlights the importance of black hole luminosity. Circinus’s accretion disk is considered moderately bright, which likely explains why its emissions are dominated by the torus. In more luminous black holes, outflows may still play a larger role. Webb now provides a reliable way to test this idea across different galaxies.

Expanding the Study to Other Black Holes

Circinus is just one galaxy among billions. With Webb’s technique now proven, astronomers plan to apply the Aperture Masking Interferometer to dozens of other nearby black holes. Building a statistical sample will help scientists understand how mass, accretion disks, and outflows relate to a black hole’s power and its impact on galaxy evolution.

This approach opens the door to a deeper understanding of how galaxies grow and change over cosmic time. By separating the contributions of feeding and feedback processes, astronomers can finally study these mechanisms directly instead of relying solely on models.

A Broader Look at Supermassive Black Holes

Supermassive black holes are now believed to exist at the centers of most large galaxies. While they are invisible by nature, their influence is anything but subtle. Through accretion and outflows, they can regulate star formation, shape galactic structures, and even affect the distribution of matter on vast scales.

Webb’s observations of Circinus demonstrate that high-contrast infrared interferometry is a powerful new tool for studying these extreme environments. As more galaxies are observed with this technique, astronomers expect to uncover patterns that were previously hidden, bringing us closer to a unified understanding of black hole behavior.

The Circinus galaxy may be relatively close in cosmic terms, but the insights gained from Webb’s observations reach far beyond it. This is a clear example of how new technology can overturn decades of assumptions and push our understanding of the universe into entirely new territory.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66010-5