New Research Suggests Cleaning Up Dangerous Space Debris Is Technically Possible and Economically Viable

High above Earth, millions of human-made objects are speeding through orbit at more than 15,000 miles per hour. Some are inactive satellites, others are discarded rocket parts, and many are fragments created when spacecraft collide or explode. Together, they make up what is commonly called space debris or space junk—and it is becoming one of the most serious long-term threats to space operations.

A recent study led by researchers at Stevens Institute of Technology takes a close, data-driven look at this growing problem. The research doesn’t just describe how bad the situation is; it also asks a more practical question: Can space debris actually be cleaned up in a realistic, commercially viable way? According to the study, the answer is yes—under the right conditions.

Why Space Debris Is Such a Serious Problem

Space debris exists in all shapes and sizes. Some objects are as large as buses, while others are smaller than a coin. What makes them dangerous isn’t their size alone, but their extreme speed. At orbital velocities, even a fragment just a few millimeters wide can cause catastrophic damage.

For operational satellites, this means constant risk. A tiny impact can destroy solar panels, disable instruments, or completely end a mission. To avoid collisions, satellite operators are often forced to maneuver their spacecraft, which burns fuel, shortens satellite lifespans, and increases costs.

The danger extends beyond satellites. Astronauts aboard the International Space Station also face risks, particularly during spacewalks, when they are more exposed. With more than 100 million debris objects smaller than one centimeter estimated to be in orbit, the odds of collision continue to rise.

Without intervention, the situation could spiral further. Collisions create more debris, which increases the chance of additional collisions—a scenario known as runaway debris growth, sometimes referred to as a cascading effect.

The Lack of Rules and Incentives in Orbit

One of the biggest obstacles to solving the space debris problem is not technological—it’s economic and political. There are no binding international regulations that force countries or companies to clean up the debris they leave behind. There is also no effective “polluter pays” system with real consequences.

As a result, space has become something of a shared but unmanaged environment, where everyone benefits from cleaner orbits, but no one wants to bear the cost of maintaining them. This creates what researchers describe as a cosmic free-for-all.

Studying Cleanup Through a Commercial Lens

The new study, published in the Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, focuses on whether debris removal could make sense as a commercial activity, rather than a purely governmental responsibility.

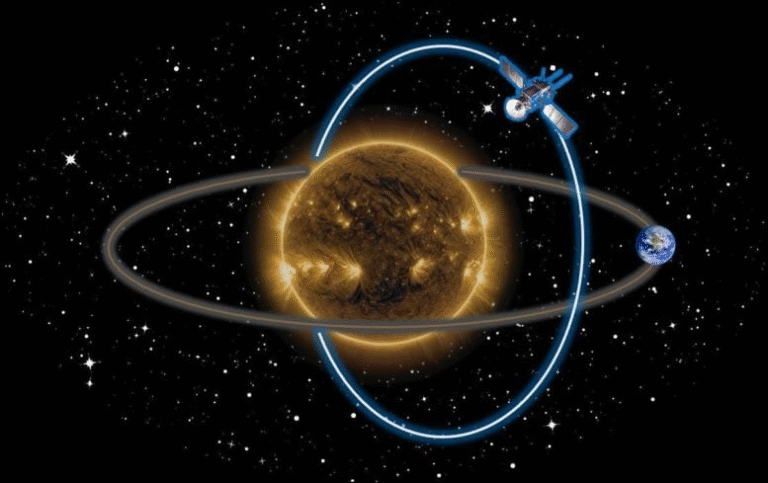

The researchers examined the role of space debris remediation satellites—specialized spacecraft designed to capture debris and remove it from orbit. They analyzed three distinct cleanup strategies, each with different technical requirements, costs, and benefits.

Three Possible Ways to Remove Space Debris

1. Uncontrolled Reentry

In this scenario, a cleanup spacecraft captures a piece of debris and lowers it to about 350 kilometers above Earth. From there, the debris naturally decays in orbit until it reenters the atmosphere.

The debris may burn up completely or partially survive and land somewhere on Earth, depending on atmospheric drag and material composition. Because the cleanup vehicle doesn’t need to descend very far or make repeated deep maneuvers, this method is the least expensive of the three.

However, the lack of control over where debris lands makes this option controversial.

2. Controlled Reentry

Controlled reentry takes the debris much closer to Earth—down to roughly 50 kilometers altitude—before releasing it, ensuring that it burns up safely or lands in a predetermined location.

This approach is safer but significantly more expensive. The cleanup spacecraft must use more energy and fuel to descend deeper into Earth’s atmosphere and then climb back up to collect additional debris.

3. Recycling in Space

The most forward-looking option involves transporting debris to a space-based recycling facility. While this requires fuel and advanced infrastructure, it offers a major advantage: reusing materials already in orbit.

Aluminum, commonly used in spacecraft, is particularly valuable. Launching material from Earth costs around $1,500 per kilogram, so recycling metals in space could save enormous amounts of money in the long term.

Who Pays for Cleanup and Who Benefits?

One of the most important parts of the study focuses on incentives. Right now, debris removal companies would bear all the costs of cleanup, while satellite operators would enjoy most of the benefits—safer orbits, fewer avoidance maneuvers, and lower operational risks.

To analyze this imbalance, the researchers applied game theory and Nash bargaining theory. Their goal was to determine how costs and benefits could be fairly shared between debris remediators and space operators.

The findings suggest that debris removal generates a net economic surplus. In simple terms, the overall benefits—such as longer satellite lifespans and reduced collision risks—outweigh the costs of cleanup. The challenge is distributing those benefits fairly.

A Proposed Solution: Fees for Space Operators

The study proposes the creation of fees paid by space operators to fund debris cleanup. Since satellite owners benefit directly from safer orbital environments, they would contribute financially to remediation efforts.

Under this model, a governing agency would oversee the system, ensuring that debris removal companies are compensated and that cleanup efforts remain economically sustainable.

The research shows that when costs and benefits are shared appropriately, both debris remediators and space operators come out ahead.

Why This Matters for the Future of Space

As more satellites are launched—especially large constellations for internet and communication services—the debris problem will only grow unless active steps are taken. Without cleanup, future missions could become riskier, more expensive, or even impossible in certain orbital regions.

This study adds an important piece to the conversation by showing that space debris removal is not just technically feasible, but economically rational when incentives are aligned.

Additional Context: Space Debris by the Numbers

- Millions of debris objects currently orbit Earth

- Over 100 million fragments are smaller than one centimeter

- Orbital speeds exceed 15,000 mph

- Even millimeter-scale impacts can destroy satellites

- Collision avoidance maneuvers consume fuel and reduce mission lifetimes

The Bigger Picture

Space is becoming an increasingly crowded and valuable environment. Satellites support navigation, communication, climate monitoring, disaster response, and scientific research. Protecting these assets means treating orbital space as something that requires active management, not passive use.

This research moves the discussion beyond warnings and into practical solutions, showing that with the right economic structures, space cleanup can become part of a sustainable and profitable space industry.

Research Paper Reference:

https://doi.org/10.2514/1.A36465