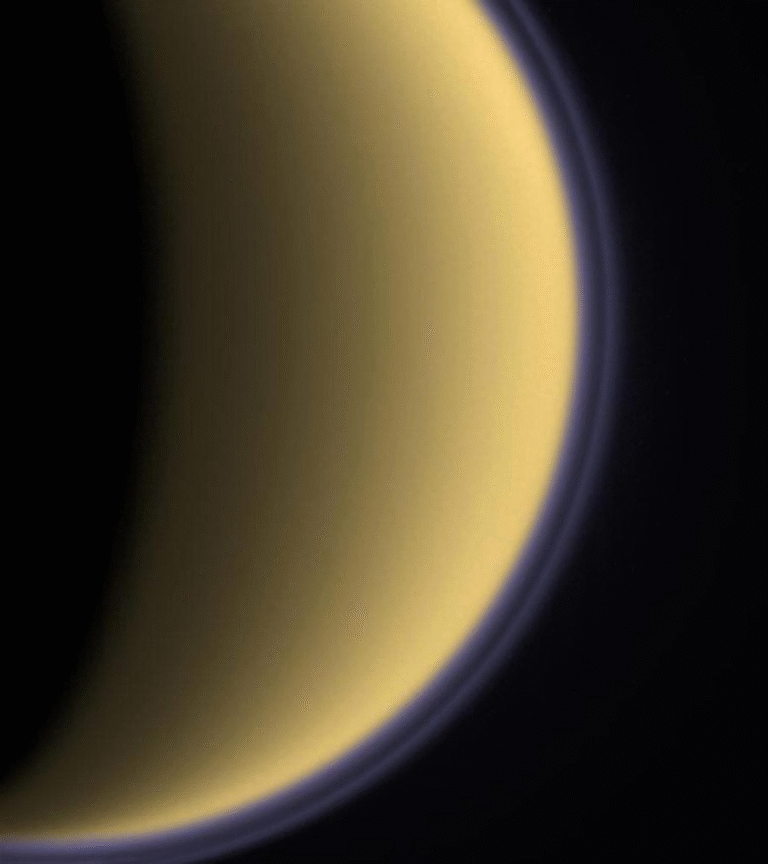

New Research Suggests Saturn’s Largest Moon Titan May Not Have a Global Subsurface Ocean After All

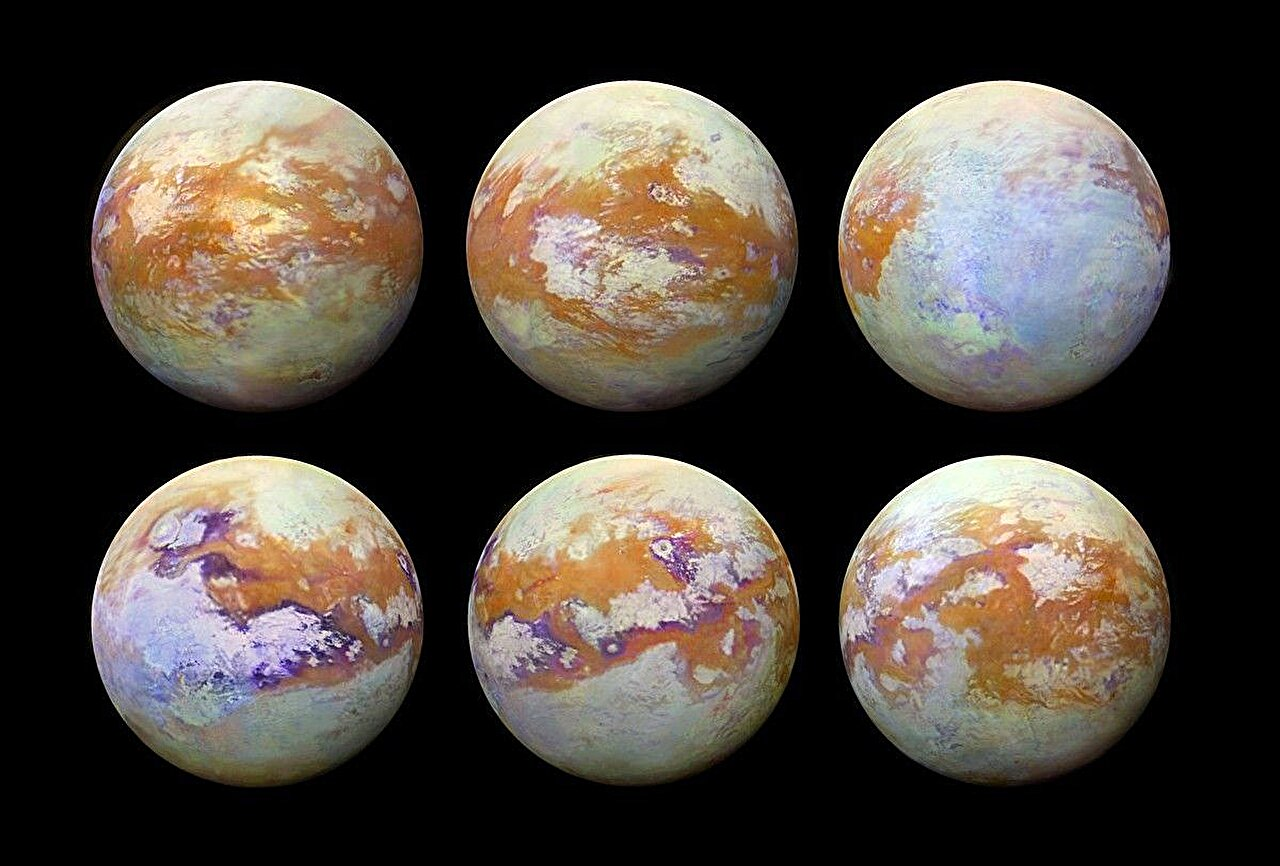

For years, Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, has held a special place in planetary science. It is one of the most intriguing worlds in our solar system, known for its thick hazy atmosphere, rivers and lakes of liquid methane, and long-standing evidence that hinted at a vast ocean of liquid water hidden beneath its icy shell. That idea helped place Titan among the most promising candidates in the search for extraterrestrial life.

Now, a careful reanalysis of data from NASA’s Cassini mission suggests that this picture may need a major update. According to a new study published in Nature, Titan likely does not have a global subsurface ocean after all. Instead, its interior may be dominated by thick ice, slushy layers, and isolated pockets of meltwater, fundamentally changing how scientists understand the moon’s internal structure and its potential habitability.

Why Scientists Once Believed Titan Had an Ocean

The idea of a subsurface ocean on Titan dates back to observations made during the Cassini mission, which launched in 1997 and studied Saturn and its moons for nearly two decades. Titan quickly stood out. It is the only body besides Earth known to have stable liquid on its surface, although these liquids are methane and ethane rather than water. Surface temperatures hover around minus 297 degrees Fahrenheit, far too cold for liquid water to exist openly.

Scientists suspected liquid water might exist beneath Titan’s icy crust because of how the moon responds to Saturn’s powerful gravitational pull. As Titan follows its elliptical orbit, Saturn’s gravity stretches and compresses the moon, causing measurable deformations. Early analyses showed that Titan deformed more than expected for a completely frozen body.

At the time, the simplest explanation was the presence of a large, global ocean of liquid water beneath the ice. Such an ocean would allow the outer shell to flex more easily, matching the deformation observed by Cassini.

A Fresh Look at Old Data Changes the Picture

The new study revisited Cassini’s radio science and gravity data, but with more advanced models and a deeper understanding of how ice and water behave under extreme pressure. While earlier work focused mostly on the amount of deformation, this research examined timing.

Scientists discovered that Titan’s shape changes lag behind Saturn’s gravitational pull by about 15 hours. This delay turned out to be critical. If Titan had a global ocean similar to Earth’s seas, its response would be much faster. Instead, the lag suggests that Titan’s interior behaves more like a thick, viscous substance, comparable to slush rather than liquid water.

The study also found that Titan dissipates far more energy during these tidal interactions than expected. This strong tidal dissipation is difficult to explain with a global ocean model but fits well with a structure made of partially melted ice mixed with solid layers.

In simple terms, Titan does not behave like a water balloon under pressure. It behaves more like frozen honey being slowly stirred.

What Titan’s Interior Likely Looks Like Now

Based on the updated analysis, researchers propose a new internal model for Titan. Instead of a continuous ocean encircling the moon, Titan likely has:

- A thick icy crust at the surface

- Beneath it, layers of ice mixed with slush, where ice and liquid water coexist

- Localized pockets of liquid water, possibly near the rocky core

- Immense pressures that cause water and ice to behave very differently than they do on Earth

The watery layer inside Titan is believed to be extremely thick, with pressures so intense that the physical properties of water change. This is where laboratory experiments played a crucial role. By simulating these extreme conditions, researchers were able to predict how Titan’s interior should respond to gravitational forces — predictions that closely matched Cassini’s observations.

Why This Matters for the Search for Life

At first glance, losing a global ocean might seem like bad news for Titan’s habitability. A large ocean provides space, stability, and chemical mixing — all qualities that can support life. However, scientists emphasize that the new findings are not a dead end.

In fact, slushy layers and isolated water pockets could still be biologically interesting. Models suggest that some of these freshwater pockets could reach temperatures as high as 68 degrees Fahrenheit. In smaller volumes of water, nutrients and energy sources would be more concentrated, potentially making it easier for simple life forms to survive.

Rather than imagining fish swimming in a dark ocean, scientists now compare Titan’s potential habitats to Earth’s polar environments, where microbes thrive in briny channels, ice fractures, and subglacial lakes.

Titan’s Unique Place in the Solar System

Even without a global ocean, Titan remains one of the most complex and fascinating moons ever studied. It has:

- A dense nitrogen-rich atmosphere, thicker than Earth’s

- Methane rain, rivers, and seas shaping its surface

- Organic chemistry that mirrors some of the processes that may have occurred on early Earth

These characteristics alone make Titan a natural laboratory for understanding prebiotic chemistry and how life-friendly conditions might arise in unexpected places.

Implications for Future Exploration

The updated view of Titan’s interior arrives at an important moment. NASA’s Dragonfly mission, scheduled for launch in 2028, will send a nuclear-powered rotorcraft to explore Titan’s surface. Dragonfly will study the moon’s chemistry, geology, and potential habitability in unprecedented detail.

Understanding Titan’s interior structure helps scientists refine where to look and what to measure. If subsurface water exists only in pockets rather than a global ocean, future missions may focus on regions where internal heat and chemistry are most likely to interact.

The new findings also encourage scientists to revisit other ocean world candidates. Titan’s case shows that tidal deformation alone may not be enough to confirm the presence of subsurface oceans without considering energy dissipation and internal viscosity.

A Reminder of How Science Evolves

One of the most interesting aspects of this discovery is that it comes from reexamining old data rather than collecting new measurements. Cassini’s mission ended in 2017, yet its data continues to reshape planetary science years later.

This study highlights how scientific understanding evolves as models improve, laboratory experiments advance, and researchers ask more precise questions. Titan has not become less interesting — it has simply become more complex.

The Big Takeaway

Titan may not host a vast underground ocean as once believed, but it still contains water, energy, and chemical complexity beneath its icy shell. The moon remains a prime target in the ongoing search for life beyond Earth, even if that life might exist in slushy channels and hidden pockets rather than a global sea.

As future missions like Dragonfly prepare to explore Titan up close, scientists now have a clearer, more nuanced picture of what lies beneath its frozen surface — and plenty of reasons to keep looking.

Research Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09818-x