New Supercomputer Simulations Reveal How Black Holes Produce Extreme Light

Black holes are often described as cosmic vacuum cleaners that swallow everything nearby, including light itself. Yet paradoxically, some of the brightest objects in the universe are powered by black holes. A new study has now provided the clearest and most detailed explanation yet of how this happens, using cutting-edge simulations that model black hole environments more accurately than ever before.

A team of computational astrophysicists has developed the most comprehensive simulations to date showing how matter falling into black holes generates intense radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum. These results not only improve our understanding of how black holes shine, but may also help explain mysterious objects recently discovered in the early universe.

Simulating Black Holes Without Shortcuts

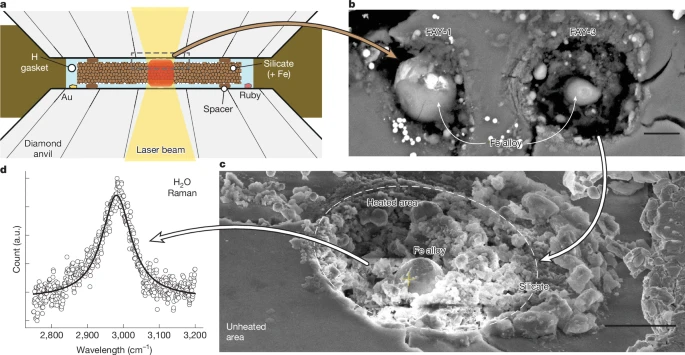

At the heart of this breakthrough is a major technical achievement. Previous simulations of black hole accretion relied on simplifying assumptions, especially when it came to radiation. Many older models treated light almost like a fluid, an approximation that makes calculations easier but does not reflect how radiation truly behaves.

In this new work, researchers avoided those shortcuts entirely. They performed simulations that include a full treatment of radiation transport combined with Einstein’s general theory of relativity. This means the calculations account for how intense gravity warps space-time and alters the paths of photons as they interact with hot, infalling gas.

According to the research team, this is the only existing algorithm capable of solving these equations accurately without making unrealistic assumptions or demanding impossible levels of computing power. The result is a far more faithful picture of what actually happens near a black hole.

A Stable Disk in a Violent Environment

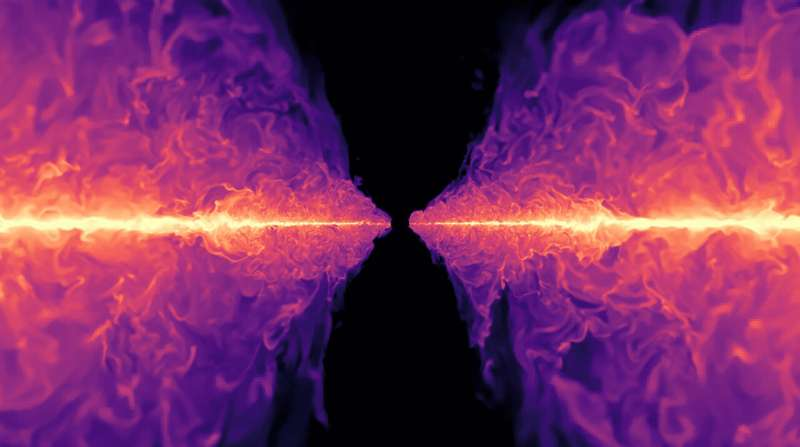

The simulations focus on how matter behaves as it spirals toward a black hole. As gas and dust fall inward, they form an accretion flow consisting of a dense, thin thermal disk surrounded by a magnetically dominated envelope. This environment is chaotic, turbulent, and dominated by radiation pressure.

Despite this violence, one surprising result stands out: the central thermal disk remains remarkably stable. Even while the surrounding flow is highly turbulent and radiation-dominated, the disk structure persists. Magnetic fields play a crucial role here, helping stabilize the system and regulate how energy and matter move.

This combination of turbulence, radiation, and magnetic fields turns the accretion flow into an extremely efficient light-producing machine, explaining why black hole systems can outshine entire galaxies.

Connecting Simulations to Real Observations

One of the most important outcomes of this study is how closely the simulations match real astronomical data. The researchers compared their results with observed light spectra from known black hole systems and found remarkably strong agreement.

This is especially valuable for stellar-mass black holes, which typically weigh about ten times as much as the Sun. Unlike supermassive black holes, stellar-mass black holes cannot be directly imaged and appear only as points of light. Astronomers must rely on spectral data to infer what is happening around them.

Because stellar-mass black holes evolve on timescales of minutes or hours rather than centuries, they provide an ideal laboratory for testing models of accretion. The new simulations successfully reproduce behaviors seen in X-ray binaries and ultraluminous X-ray sources, giving scientists greater confidence in how they interpret observational data.

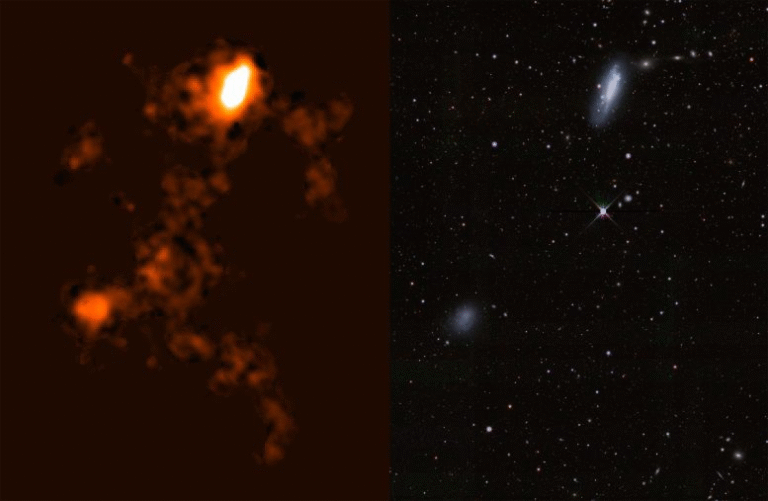

Explaining the “Little Red Dots” Seen by JWST

The findings may also solve a cosmic mystery uncovered by the James Webb Space Telescope. JWST has detected hundreds of faint, reddish objects in the early universe, often referred to as little red dots. These objects are too bright and compact to be explained easily by standard galaxy models.

A leading hypothesis suggests that these dots are black holes growing rapidly through a process called super-Eddington accretion, where the black hole emits more light than expected from classical limits. The new simulations strongly support this idea.

The models show that black holes can indeed radiate above the traditional Eddington limit when accretion is not perfectly spherical. In these cases, radiation escapes through complex geometries shaped by magnetic fields and turbulence, allowing the system to shine far more brightly than previously thought.

Supercomputers Powering Astrophysical Discovery

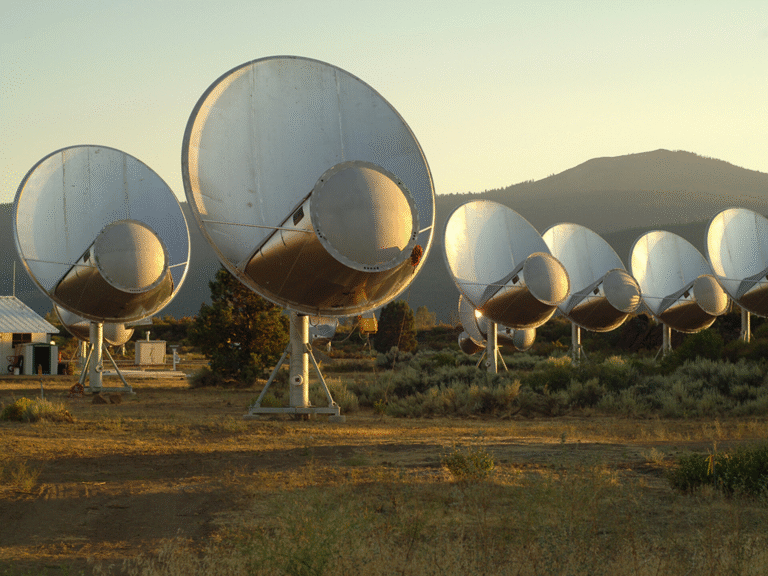

Achieving these results required access to some of the most powerful computers ever built. The team ran their simulations on Frontier and Aurora, two exascale supercomputers located at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Argonne National Laboratory. These machines can perform a quintillion calculations per second, making it possible to tackle equations that were once considered intractable.

Even with this immense power, advanced algorithms were essential. The radiation transport method was designed to track how light moves in different directions and interacts with matter under extreme gravity and strong magnetic fields. This work builds on earlier methods that are now widely used across astrophysics, but pushes them into entirely new territory.

Why General Relativity Is Essential

Black holes are regions where gravity is so intense that Newtonian physics breaks down. Any realistic model of black hole accretion must include general relativity, which describes how massive objects bend space and time.

In these simulations, relativistic effects determine not just how matter falls inward, but also how radiation propagates, scatters, and escapes. Light emitted close to the black hole can be bent, redshifted, or even trapped temporarily before escaping, all of which affect what distant observers see.

By including these effects self-consistently, the simulations provide a much clearer link between physical processes near the black hole and the light detected by telescopes.

Jets, Winds, and Outflows

The simulations also capture the formation of powerful winds and, in some cases, relativistic jets. These outflows carry energy and matter away from the black hole and can influence their surroundings on much larger scales.

Jets are especially important because they can extend far beyond the host system and affect star formation in nearby regions. Understanding when and how jets form depends critically on magnetic fields, black hole spin, and accretion rate—all factors included in the new models.

Looking Ahead to Bigger Black Holes

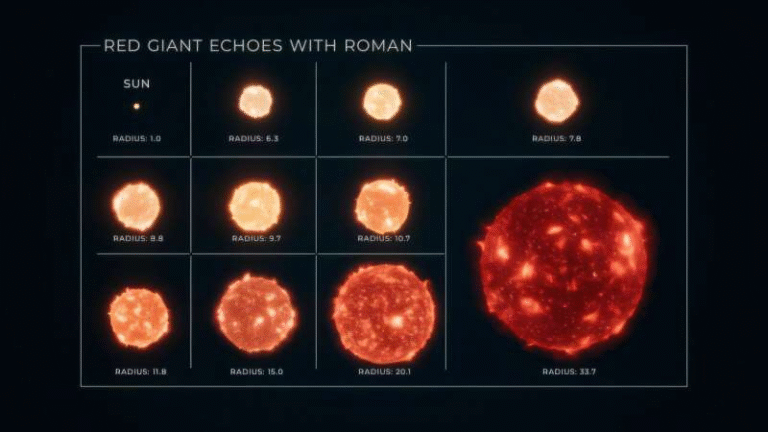

Although this first paper focuses on stellar-mass black holes, the researchers plan to extend their approach to supermassive black holes, which sit at the centers of galaxies and help drive their evolution. If the same physics applies across mass scales, these simulations could transform our understanding of active galactic nuclei and quasars.

Future work will also refine how radiation interacts with matter across a wide range of temperatures and densities, making the models even more versatile.

Why This Study Matters

This research marks a major step forward in computational astrophysics. By removing long-standing approximations and fully embracing the complexity of radiation and relativity, scientists now have a powerful new tool for exploring some of the universe’s most extreme environments.

From explaining why black holes shine so brightly to shedding light on mysterious early-universe objects, these simulations bring theory and observation closer together than ever before.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ae0f91